Annie Koo

Nov. 27 2007

For the self-selecting visitor, an industrial ruin’s appeal seems nebulous. Tim Edensor suggests a “post-industrial nostalgia” that appreciates a “vicarious engagement with fear…and one’s own vulnerability and mortality” (Edensor 13). True, a vague sense of secrecy and danger envelops Fox Point’s Crook Point, but specifics are difficult to pinpoint. Does dereliction necessarily warrant subversive appeal? What about a site’s rogue identity attracts the visitor? At Crook Point, the link between physical cause and psychological effect deserves exploration. Consideration of its abandoned aesthetic, government disacknowledgment, and local folklore further articulate Crook Point’s strange attraction.

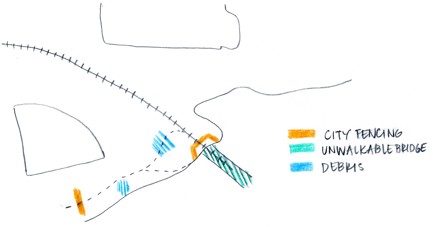

Crook Point’s initial appeal lies in its inaccessibility. A mangled chain-link gate punctures a muddied pathway meandering from the water’s edge through overgrown brush, up to the rusted tracks of the old East Side Railroad. Smaller paths branch off of this decrepit spine at the behest of more adventurous users. Debris litters the entire site, reminders of its continued, if not discarded, use. Soda bottles and white plastic siding garnish one clearing in the path. A collection of grocery bags hovers at another. Irreverent splashes of teal, magenta, and black graffiti disrupt Crook Point’s rust- and bark-brown palette. Such are the aesthetics of inaccessibility: the visitor is forewarned first by the fence and then the debris-ridden pathway that the site is not intended for him. The graffiti suggests other subversive users before her. Even the bridge deters access. Foot-wide gaps between its planks demand a balancing act to cross (Appendix A). Taken together, these aesthetics comply with Michel Foucault’s fifth principle that heterotopias discourage easy admission (Foucault). Privy to these codes of exclusion, the visitor is aware of his “out-of-placeness” but excited by his defiance. She trespasses in response to—or at least with an understanding of—these aesthetic deterrents. The appeal of Crook Point takes root in these physical markers of its inaccessibility and the thrill they conjure.

The physical contrast between Crook Point’s natural landscape and its human remnants is no less enticing to the visitor. The site seems at once abandoned but well trod, harking to Foucault’s third principle of incompatibility of usage (Foucault). Its simultaneity of experience disorients the visitor. He feels alone yet cannot shake the presence of other users in the graffiti and debris. Thus, the visitor (who is already contending with its exciting inaccessibility) finds further thrill in Crook Point’s complex heterotopic experience. Notions of disobedience and detachment confound the site but captivate the visitor.

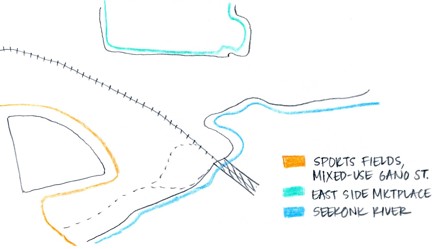

Crook Point’s heterotopic appeal is not only site-specific, but extends also to its greater urban context. Tim Edensor argues for the industrial ruin’s role in diversifying the modern cityscape. Unlike the city’s “machinic apparatus of policing, planning regulations…[and] bounding of discrete spaces”, the marginalized wasteland is weakly classified, permitting a “wide range of encounters and greater self-governance” (Edensor 54). Indeed, Crook Point’s abandoned tracks and debris do not decree—or even suggest—specific uses. Tagging, littering, and even fishing qualify as approved behaviors. This contrasts sharply with the highly keyed programs surrounding the site. East Side Marketplace bounds Crook Point to the north; neighborhood sports fields and Gano Street’s residential-commercial spattering are to the west; the Seekonk River flows to the south and east (Appendix B). Nestled between these asphalt parking lots and cultivated greenery, the wasteland’s appeal emerges from its very indistinction.

Overgrown weeds and standing water host activities otherwise condemned. Before its blockage in 1993, the abandoned East Side Railroad tunnel was notorious for its parties. “Bob E.” describes an early 1980s RISD-student party at the tunnel’s Benefit Street entrance as “tribal in nature—kind of like a proto Rave party” (“East Side Railroad Tunnel”). He recalls “drums, torches, bonfires, running naked, and chanting” at the event. Traditional urban spaces, by articulating order, would resist such unconventional activity. But Crook Point remains loosely defined, permitting events like the legendary 1993 Beltain-Day party that prompted the city to seal off the tunnel (“East Side Railroad Tunnel”). It is this possibility of usage—its openness to subversive program—that warrants Crook Point’s appeal. Edensor calls it a “lingering fascination with the possibilities available at weakly regulated occasions and spaces, a desire for the sensual, disorderly experience of raves” (Edensor 59). Counter-culture visitors, for whom traditional cityscapes are too rigid, are particularly seduced by Crook Point’s “wildness”. Their parties are proof.

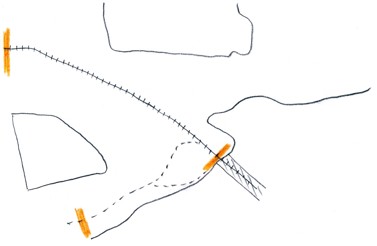

The city’s intervention at Crook Point—or lack thereof—confirms this sense of excitement. Its chain-link fence at Crook Point’s Fox Point entrance and barbed wire fence around the bridge indicate attempts to thwart visitors. But their disrepair speaks even louder. The bridge fence is trampled, its barbed wire stamped into uselessness. Chain-link panels hang off its frame, allowing easy access to the bridge. The entrance gate hangs even more ironically. A clear footpath bypasses the gate, rendering the gate useless except as a reminder of the city’s ineffective regulation of Crook Point. The tunnel’s corrugated steel doors—though perhaps more effective in blocking usage—also symbolize the city’s failure at fully marginalizing the site. These physical markers of city intervention heighten the visitor’s experience. However contrived, he is liberated from governmental control in this urban space, free from the classification that persists in traditional zones. As with the inaccessibility of Crook Point, it is a subtle triumph for the visitor who uses the site in defiance of these restrictions. He is excited by his insubordination of governmental control. The city thus underlines Crook Point’s heterotopic thrill (Appendix C).

This thrill of government insubordination finds physical fruition in Crook Point’s graffiti art. The site’s transgressive nature (first asserted by the disregarded city boundaries) seems to warrant further illegality. The site’s subversive aura goes beyond just encouraging users to trespass against city restriction. It empowers them to document their deviance. Colorful graffiti of all shapes and sizes proclaim this through political statements, religious messages, or simple names. On one particular visit, I witnessed several kids tagging their names. Theirs was a lighthearted encounter with Crook Point. More consumed with where to put their name, they seemed unphased by their disobedience. But such is the vibrancy of Crook Point’s subversive appeal. The graffiti, as an advertisement of the site’s delinquency, attracts a wide range of self-selecting visitors. As visual evidence of Crook Point’s dereliction, it both reinforces and contributes to the site’s rogue identity.

But Crook Point’s appeal runs deeper than aesthetic predispositions and governmental disacknowledgment. It has been cultivated for generations in the imagination of an entire neighborhood. Crook Point’s official abandonment in 1981, aside from catalyzing decades of dereliction, initiated a vibrant local folklore about the site. Stories of abandonment and youthful adventure replace its original identity as a bustling transportation zone. To the well-versed visitor, its permanently upturned steel trusses are symbolic, not of industrialism, but of the site’s neglect. Edensor notes the appeal of such sites to local culture and children. Ruinous spaces provide “limitless encounters with the weird, with…peculiar things and curious spaces which allow wide scope for imaginative interpretation” (Edensor 4).

For evidence of Crook Point’s local fixation, one need look no farther than Providence’s youth. Discussions with former area high school students reveal traditions centered on the tunnel. According to some, kids were once dared and expected to stand in the tunnel for as long as possible (Personal Interview). For others, it was a “[rite] of passage to finish off a 40 oz. of Haffenreffer (or two) and make your drunken way to the other end”. Still other respondents recount experiences traversing the tunnel as “cathartic” and “awesome” (“East Side Railroad Tunnel”). These personal stories suggest a greater urban discourse centered on Crook Point’s reputation for adventure and urban legend. The continuation of these myths secures its appeal for future generations.

Of course, Crook Point’s appeal is not unanimous. Its heterotopic allure and liberation from spatial regulation hold little fascination for those uncomfortable in loosely defined, run-down areas. But for those self-selecting visitors that regularly visit Crook Point, its attraction is articulated through these aesthetic codes of dereliction. Markers of inaccessibility, government disacknowledgment, and participation in a greater local folklore evince the visitor of Crook Point’s rogue—and thus appealing—identity.

Appendix A: Markers of Inaccessibility

Appendix B: Surrounding Program

Appendix C: Evidence of Government Intervention

Appendix D: Assorted Pictures

Entrance "gate" intended to deter access to Crook Point

Debris deposit along pathway

Barbed-wire fence almost surrounding bridge

Works Cited

“East Side Railroad Tunnel,” 2007, Art in Ruins website, 25 November 2007, < http://www.artinruins.com/arch/?id=decay&pr=eastsidetrain>

Edensor, Tim. Industrial Ruins: Spaces, Aesthetics, and Materiality. (Oxford; New York: Berg, 2005).

Foucault, Michel. "Of other spaces, heterotopias", 1967 in Architecture/Mouvement/ Continuité (October 1984).

Personal Interview, Former Moses Brown student. November 2007.