|

|

|

|

Return to Equinoxes, Issue 1 : Printemps/Eté 2003

Article ©2003, Alexa Wright

Images 2-10 of works ©Alexa Wright

Alexa Wright is a visual artist working with photography and digital media. She exhibits nationally and internationally and is based in London.

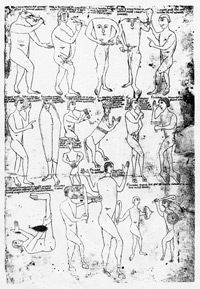

As a visual artist, my interest in monsters was sparked when I discovered this image from the Crusaders Handbook in a library book more than ten years ago. I was entranced by the graphic description of a literal embodied otherness.

As a visual artist, my interest in monsters was sparked when I discovered this image from the Crusaders Handbook in a library book more than ten years ago. I was entranced by the graphic description of a literal embodied otherness.

The depiction of the "other" as monstrous has existed since the first recorded descriptions of the Monstrous races, dating from the 4th century BC. At this time, Ktesias of Knidos and Megasthenes describe the inhabitants of India as having strange forms which seem to be derived from a mixture of myth and misperception. These Monstrous Races, based on descriptions of people encountered by such travellers as Alexander the Great, were believed to exist until well into the Middle Ages. They were recorded in many different texts and drawings, such as the one pictured above from the 12th century. The Monstrous Races inhabited places beyond the edge of the known world. Although this was generally the known world of the Greeks and Romans, there are also many similar creatures in Indian mythology. The projection of fears and anxieties onto unknown or unfamiliar territories, whether these be geographical or human, physical or psychological, is universal. It is in these territories, at the borders of the known world, that monsters reside, policing the boundaries between "us" and "them."

For me, one of the most interesting things about the Monstrous Races is their literal embodiment of the perception of the "other" who is "like us" and yet distinctly "not like us." These "others," of which there are many different kinds with both physical and behavioural oddities, were widely believed to exist with the physical form and strange attributes such as those depicted here. Examples are the dog-headed men who lived in caves in India, as well as the Blemmaye who lived in the deserts of Libya and who have no head but a face in their chest. The Blemmaye have a long history and were even mentioned by Shakespeare as "men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders." From a contemporary perspective, the Monstrous Races are clearly a result of the overlaying of misunderstandings, fears and prejudices onto perceptions of the physical form of real people. However, although our materialistic, scientific means of explaining the world is relatively recent, it is difficult to un-think this and to understand that before the 17th century, myth and physical, or perceptual fact were of equal significance, and considered equally valid as means of explaining the world. Truth was not simply concerned with the perceived surface of things, but incorporated magical, or symbolic explanations. If we accept that, even in the contemporary context, all bodies are social and symbolic as well as physical, the Monstrous Races offer an illustration of the processes we all go through in one way or another in perceiving all others, and also in perceiving ourselves as other.

When I first saw this image of the Monstrous Races, I was just beginning to investigate the idea of the uncanny body - of the material self as abject - in work for which I was photographing surgery. My 1993 piece, Stranger Within, consists of a series of four images of orthopaedic surgery. Here, I was working with ideas of the cyborg and the boundaries of the self. However, when I showed the images of the acceptable surface of the body opened up, I became interested in the audience's reactions. These reactions demonstrated how our common material reality is somehow seen as difficult, disgusting, and, in a way, monstrous.

Fig. 2: Stranger Within, 1993

Fig. 2: Stranger Within, 1993

The monstrous is generally defined as residing in the abnormal or the unnatural, but here the normal, natural body becomes monstrous when experienced differently (i.e. visually rather than proprioceptively).

Fig. 3: Precious 4, 1995

Fig. 3: Precious 4, 1995

I first started working digitally in 1995. Precious is a series of seven images in which I use Photoshop to ask the viewer to readdress his or her reactions to seeing the interior of the body. Relocating the surgical images in a new, mythological, or art-historical context, my intention was to offer the space for the viewer to examine his or her own reactions to the images of open wounds. This is work in which the body is seen as a fragment - it is a generic body, rather than that of anyone in particular.

In 1997, After Image, a series of twenty-four digitally manipulated photographic portraits, was intended to represent the subjective experiences of people with phantom limbs. The project, involving a collaboration with neuropsychologist Peter Halligan, neurologist John Kew, and eight people with limbs amputated, was sponsored by a Wellcome Trust SciArt award.

Fig. 4: After Image RD2, 1997

Fig. 4: After Image RD2, 1997

The phantoms described by the subjects of this work raise all sorts of interesting questions about authenticity. The phantoms are so real for the people with whom I worked that I was led, in a very direct way, to question which is the real body - that which we can see, or that which the person experiences? Peoples' descriptions of their relationship with their phantom as a part of them that other people do not acknowledge, and which is both a desirable memento of the (physically) lost limb, and at the same time a painful encumbrance, suggests a curious borderline relationship with the phantom body-part, which perhaps takes on a monstrous quality in its resistance to intelligibility.

I am interested in the questions that the phenomenon of phantom limbs raises about where the self begins and ends, and the extent to which the body is representative of the self. Through this work I also became interested in the public rejection of physical difference as unacceptable or monstrous.

Fig. 5: After Image GN3, 1997

Fig. 5: After Image GN3, 1997

Reactions to this image in particular led me to make the next series of work. It is both interesting and frightening that this image has been condemned for being "too real," too much like the representation of a real physical disfigurement, which some people have found intolerably threatening. This is precisely the point at which the monstrous arises - in the body that is seen as both human and non-human - the threat residing in the fact that the viewer can identify with the body of the subject of the work as possibly his or her own. Traditionally, monstrous bodies have been subject to lack or excess, somehow defying a perceived natural order, and representing a threat to subjectivity.

The proliferation of ideal (and "normal") body images that are designed to displace self-image and to render it monstrous, inhabits a parallel realm to that of the monstrous body. Both are phantoms layered over the material body, which is in itself, according to Kate Soper, "a being that is the source and site of its own experience of itself as an entity."3

'I', made in 1998/9, is a series of eight digitally manipulated photographs in which my own body has been literally conjoined with those of people with congenital physical disabilities. I wanted the first of this series of images to refer to an ideal female image, in which the deformity, or difference, is almost unnoticeable.

Fig. 6: 'I' 1, 1998

Fig. 6: 'I' 1, 1998

I am often asked why I have replaced the identities (faces) of the people to whom these disabilities belong with my own. It is often difficult to articulate an answer to this question. My original reasons were related to diminishing the boundary between "us" and "them," and attempting to force the viewer to locate him or herself as subject of the work as he or she battles with these unreal, and yet believable, images. However, as I review the work through my study of monstrosity, I realize that I am trying to work through a more subtle and interesting idea.

If all natural bodies are perceived as undesirably monstrous, and the belief that humans are by nature monstrous is further internalised, how does the self negotiate its relation to a body that is perceived as both self and other at the same time? The self cannot easily create distance from its own monstrous body.

Fig. 7: 'I' 3, 1998

Fig. 7: 'I' 3, 1998

If every little anxiety about the disorganisation of the embodied self propagated by the media is fed by the reassuring power of science and technology to "understand" anomaly and therefore to control and correct it, then the (natural) body is always rendered the insecure subject of anxiety. This applies not only to the bodies represented in this work, but also to the body of the viewers themselves. I wanted this work to act both as a mirror of the viewer's fears and prejudices concerning other people's physical difference and of the anxieties surrounding his or her own body form or image. By Michel Foucault's definition of the monster as something which is unintelligible in itself and acts as a mirror enabling society to "see itself" from the outside4 , this is monstrous work that enables the subject to reflect on his or her own identity.

Behind reactions to different or deformed bodies is a belief that the moral or psychological value of the person is expressed physically. This conception has a long history: in early paintings, for example those of Bosch and Breughel, moral or psychological error is expressed as physical anomaly or distortion. In the second century AD, Solinus describes whole nations in Arabia whose citizens are "altogether plain without noses," and who live in "ill-favoured villages".5 These villages are presumably ill-favoured on account of the deformities of their inhabitants. Images of the physicalization of moral or psychological deviance are also common in literature: in Shakespeare, for example, the body of Richard III is represented as deformed. JJ Cohen suggests in Monster Theory, as Richard moves between monster & man, the disturbing possibility that this incoherent body, denaturalised and always in peril of disaggregation, may well be our own.6

That connection is further complicated in this work, 'I' (figs. 6 & 7). This body is my own, and yet is also others'. Monsters are constructed to conceal insecurities; if I don't know what I am, at least they help me to know what I am not. This work, 'I', contradicts this concept. Catherine, whose shoulder appears in the first of the series, said that she also feels that image to be hers. She says, "at first I felt my shoulder looked wrong on somebody else's body, but now I don't; now I see it as me." She adds, "practically every day of my life I experience comments from strangers or acquaintances, of a nature which implies that I am 'lacking' in something, that I am not whole or complete because I do not have the same number of limbs as the majority."

Fig. 8: Skin, 2000

Fig. 8: Skin, 2000

Photography has always been a powerful medium for bringing viewers into contact with people different from themselves, and has often made these other bodies into objects of display. Skin, the photo/text work featured above, was the result of a series of conversations with dermatologist Professor Irene Leigh. The images were inspired by "artfully" taken medical photographs of the conditions of some of her patients which were very much "on display," similar to a 19th century medical curiosity.

Professor Leigh talked about the trauma of her patients, who are made to feel unacceptable by the perceived contamination of the skin - the acceptable surface that forms the boundary of the self. This surface is inscribed with information about the person. If this is marked, confused or diseased, it is seen as dirty and even monstrous. In these photographs the displayed skin condition is located in a "fantasy" setting, which, rather like the jewels in my earlier work Precious, offers a different context within which to view the (monstrous) body. Although these photographs are not manipulated, they do operate like digital works - as mythological images - creating a disjuncture that enables re-evaluation of expected reactions.

Whilst taking the images out of the everyday, the work also draws on real experience. Extensive text panels, which document the often very traumatic experiences of the people I have photographed, ground the images in the experience of the subject as individual. Here, for example, is an excerpt from one subject's statement:

People look at you in the street, I know it is only curiosity, but people do look at you differently. Going into a shop and handing over your money you find people throw it back at your hand or throw it onto the counter instead of passing it into your hand. They think that you have leprosy. I was on the tube once and two ladies were standing there. I had my hand up holding onto the rail, and one of the ladies said 'can you remove your hand please?' I looked at her and I said 'it is only Psoriasis.' She said 'I don't care, can you remove your hand.' Tears welled up in my eyes and I didn't know what to do, but luckily a man tapped me on the shoulder and asked if I would like to sit down. That kind of thing is upsetting. You can feel people looking at your hands. (Noella)

In her book on classification, Harriet Ritvo explains that "as a group, monsters were united not so much by physical deformity or eccentricity as by their common inability to fit or be fitted into the category of the ordinary - a category that was particularly liable to cultural and moral construction."7

Until the late 18th century the idea of the monster was almost exclusively physical. Foucault has much to say about the 19th century transition from physical to moral monsters and about their relationship to psychology. He maintains that in the late 18th century one witnesses the emergence of a monstrous criminality or of the monster whose effect is not in nature and the disorder of the species (as is the physical monster), but in behaviour itself. ."8

Fig. 9: Suspect, 2001

Fig. 9: Suspect, 2001

Suspect is a photo/audio installation consisting of three composite portrait photographs and a spoken narrative edited from a conversation with ex-contract killer and gangster Bobby Cummings. In each of the photographs the features of three or four people are combined using Photoshop to create a single, seamless identity. The viewer first assumes that one of the portraits is the 'killer' and begins to make judgements about the faces on that basis. On realising that these are constructed images, the viewer is then left to consider his or her own judgements, and to question ideas about physiognomy, or the physical expression of psychological or moral traits.

In an extensive series of photographic portraits, 19th century criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso made direct connections between physical characteristics and mentality. According to Lombroso, criminality was the sign of a primitive form of nature: an animality within a civilized society that was a throwback to a more primitive state.9 He aligned more "brutish" physical characteristics with a brutish and criminal nature. Interestingly, although Lombroso's ideas are now seen as prejudiced and politically incorrect, this attitude is one with which many viewers approach the composite images displayed in this work.

According to Foucault, "you could say that the monster is he who combines the impossible and the forbidden…"10 Foucault makes the distinction between (mental) illness and monstrosity. Illness, he says, is something that also overturns the natural order, but it has its place within the social order. Illness, therefore, can be labelled, institutionalised and treated, whereas monstrosity is not treatable because the monstrous is not an attribute of the individual, but is a social and cultural construct.

Until the end of the 18th century, the criminal represented a sickness of, or in, the social body. Since the 19th century, however, criminality is perceived as a sickness of the individual. It is then that the "pathology of criminal conduct" begins. It is interesting to note that, in the contemporary context, if someone is deemed not to be of right mind (i.e.: to be mentally ill and unaware of what he or she is doing) this person cannot be convicted of murder. It is not the act that is deemed criminal or monstrous, but the intention. Whether this is morally right or wrong is questionable, but it does seem to have interesting implications regarding the location of the self.

Fig. 10: Killers, 2002

Fig. 10: Killers, 2002

The final work I will discuss here, entitled rather blatantly Killers, explores the idea of the moral monster, and encourages self-reflection on the part of the audience. Killers is an audio installation that examines individual and collective perceptions of self and "other." The work plays with its audience's ability to identify with others. A plain, institutional chair invites audience members to sit at each of a number of plywood "booths." These are reminiscent of polling booths or confessionals. In each booth a different monologue is accessed through headphones. These monologues are edited from conversations I had with men and women serving life sentences for murder. These compelling and emotive stories range from five to twelve minutes in length. Prisoners describe their life circumstances, the act of killing and how they feel about it. Each "story" is very different, yet at each booth the listener is put in the position of identifying with the narrator, and at the same time judging him or her.

My work uses manipulated imagery and, more recently, digital technologies in general to bring the spectator or user into an intimate and contemplative relationship with an uncertain subjectivity that he or she may own, or may reject as threateningly "other." It is this stranger, this "other," lurking at the boundaries of identity, that fascinates me; both in relation to individual subjectivity, and to the technologies that engender and continually modify our contemporary perceptions of this monstrous creature.

1 Crusader's Handbook Monstrous Races of the World 12th Century. British Library, London. MS Harley 2799, (fol.243r).

2 Stranger Within 1993 Installation shot. Three C-Type photographs, aluminium, wing nuts. Each image 85 x 112cm.

3 Precious 4 1995 From series of seven digitally manipulated photographs as C-type prints. Each 50 x 60cm.

4 After Image RD2 1997 From series of twenty four digitally manipulated photographic prints mounted on foamex. Each 56 x 75 cm; sixteen small text panels.

5 After Image GN3.

6 'I' 1 1998/9 From series of eight colour Lightjet digital prints in black wood frames. Each 80 x 105cm.

7 'I' 3.

8 Skin 2000 Five colour R-type prints mounted on aluminium; four text panels. Each 40 x 50cm.

9 Suspect 2001 Three colour Lightjet digital prints. Each 90cm square mounted on foamex, CD player and sensors.

10 Killers 2002 Installation shot at Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast. Four to eight wooden booths, adapted CD players, chairs. Dimensions variable.