|

DELENDA EST CANADA! | CANADA MUST BE DESTROYED!

There were four world-wide European wars between 1689 and 1763, each of which was primarily a contest between England and France, and each of which was fought in part on the American continent. British colonial interest in the overthrow of French power in North America had its beginnings with the King William’s War (1689-1697), when New Englanders, fed up with French attacks on their North Atlantic shipping and fishing interests, set about the task of destroying privateer haunts in Acadia. In the spring of 1690 Port Royal (Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) fell to a motley force of some seven hundred New England troops. Although it was regained by the French the following year, this initial success emboldened the government of Massachusetts to entertain hopes of neutralizing the French threat decisively, once and for all. Quebec, on a promontory overlooking the St. Lawrence River, founded by Champlain as the center of French power in Canada, became the symbol of the French threat to the British colonies. Delenda est Canada! (Canada must be destroyed), became the rallying cry of New England.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Contested Ground

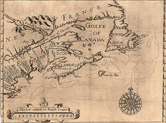

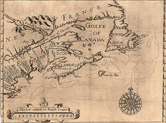

15. "[New Scotland]" In: William Alexander, 1st earl of Stirling. An encouragement to colonies, London, 1624.

16. "La Nouvelle France""In: Marc lescarbot, Histoire de la Nouvelle France, Paris 1618.

King William's War was primarily a series of bloody French and Indian raids on the northern flanks of the British colonies in New York and New England, and both English and French settlers in the contested ground bore the brunt of organized military and guerilla actions. A look at the two maps of the period shown here illustrates the overlapping territorial claims and assumptions that were to lead to prolonged hostilities between England and France until France decisively lost her territory in 1763. |

|

|

Lachine, Canada, 1689 / Schenectady, New York, 1690

17. Nicholas Bayard, A journal of the late actions of the French at Canada, London, 1693.

In the summer of 1689 news arrived at Albany that England and France were at war. Enthusiastically, the Iroquois allies of the English descended on Lachine, near Montreal, killing French settlers and destroying buildings, crops, and animals. The following winter of 1690 the French returned the favor, employing those same Iroquois tactics in their attacks against the English settlements of Schenectady, Salmon Falls, Fort Loyal, and fortified Mohawk towns (called "castles" by the English) in the Albany area. Shown here is the official account of the attack on Schenectady by Nicholas Bayard, one of the English defenders. |

|

|

Instilling Fear

18. "Canadiens en raquette." In: M. Bacqueville de la Potherie, Histoire de l'Amerique Septentrionale, Paris, 1722.

Many of the French raids on English northern frontier settlements were made by French Canadian coureurs du bois and by French soldiers camouflaged in Indian dress and war paint. The idea that white men (even Catholic white men) would attack and scalp "their own kind" was particularly horrifying to English settlers alone on the frontier. |

|

|

“[The missionaries teach the French settlers ] among other things that the Virgin Mary was a French Lady, and that her son the Saviour of the World was crucify’d by the English.” Dummer, Letter (London, 1712)

The "Religion Card"

The political agendas of England and France filtered down to the North American front lines in very personal ways. English and French fears of one another were tied closely to their abhorrence of each other’s religion—Protestant against Catholic, Catholic against Protestant. The “religion card” was a propaganda tool used with relish by both sides to demonize the other and stoke the fires of loyalty in settlers who were caught up in the conflict.

“'Oh my dear child, if it were God’s will, I had rather follow you to your grave, or never see you more in this world, then you should be sold to a Jesuit, for a Jesuit will ruin you, body and soul!’ It pleased God to grant her request, for she never saw me more!” |

|

|

Pemiquid, Maine, 1689

19. John Gyles, Memoirs of odd adventures, strange deliverances, &c. in the captivity of John Gyles, esq., Boston, 1736.

We had some that we took inform us, that if we had come but four days sooner, they had not above 600 men in town, but being so long in the river before we got up, they had notice of us, and had sent for all their strength thither, so that there was now in the town 3,000 men and eight hundred that were near us in swamps and woods, to keep us constantly alarmed.

Pemaquid, the most outlying settlement of the English on the coast of Maine, surrendered to a force of French and Maliseet Indians in 1689. John Gyles, then age nine, was abducted along with his mother and siblings and taken north to Canada. He was terrified of "Jesuits," and when a French missionary offered him a biscuit to eat he buried it–although he was very hungry–for fear that it contained some kind of magic that would make him "love" the enemy. Gyles spent six years with the Indians and three years with a French master. When finally released he spoke English, French, Maliseet, and Micmac, and was in demand as an interpreter for peace negotiations and prisoner exchanges. |

|

|

The Phips Expedition, the "Glorious Enterprise" of 1690

20. Thomas Savage, An account of the late action of the New-Englanders, under the command of Sir William Phips, against the French at Canada, London, 1691.

In October, 1690, the French turned back an attack on Quebec by a naval force led by Massachusetts governor, Sir William Phips, who was riding a wave of enthusiasm following his capture of Port Royal, Nova Scotia, the previous spring. But the outcome this time was far different. Because of a lack of competent pilots with knowledge of the St. Lawrence River, the fleet took nine weeks to reach Quebec and hope of any measure of surprise faded. In addition, many of the troops were sick with small pox, and only 1,200 of the original 2,000 were able to land. Thomas Savage, the author of this account, was a part of the expedition. |

|

|

Celebration of French Victory

21. Relation de la levee du siége de Quebec, capitale de la Nouvelle France, Paris, 1691.

On the other side, the inhabitants of Quebec rejoiced, and it was noted with satisfaction that what the English had bragged would be an easy victory did not come to pass. |

|

| |

Exhibition seen in Reading Room from september 2008 through

december 2008.

Exhibition prepared by Susan Danforth, Curator of Maps and Prints. |

|