Rhode Island Hall has had a long and fascinating history that has, thankfully, been recorded for posterity. The most complete written history of Rhode Island Hall is recorded in Mitchell’s

Encyclopedia Brunoniana, available in published form from “Friends of the Library” (Mitchell 1993), as well as online. More information regarding Rhode Island Hall is stored in the Brown University Archives at the John Hay Library, which has collected numerous documents and press clippings related to Rhode Island Hall and the museum that was originally housed inside. Combined with the archaeological evidence and material culture recovered from the 2008 to 2009 renovation, a more clear history of Rhode Island Hall and the interactions between people and the building can be reconstructed.

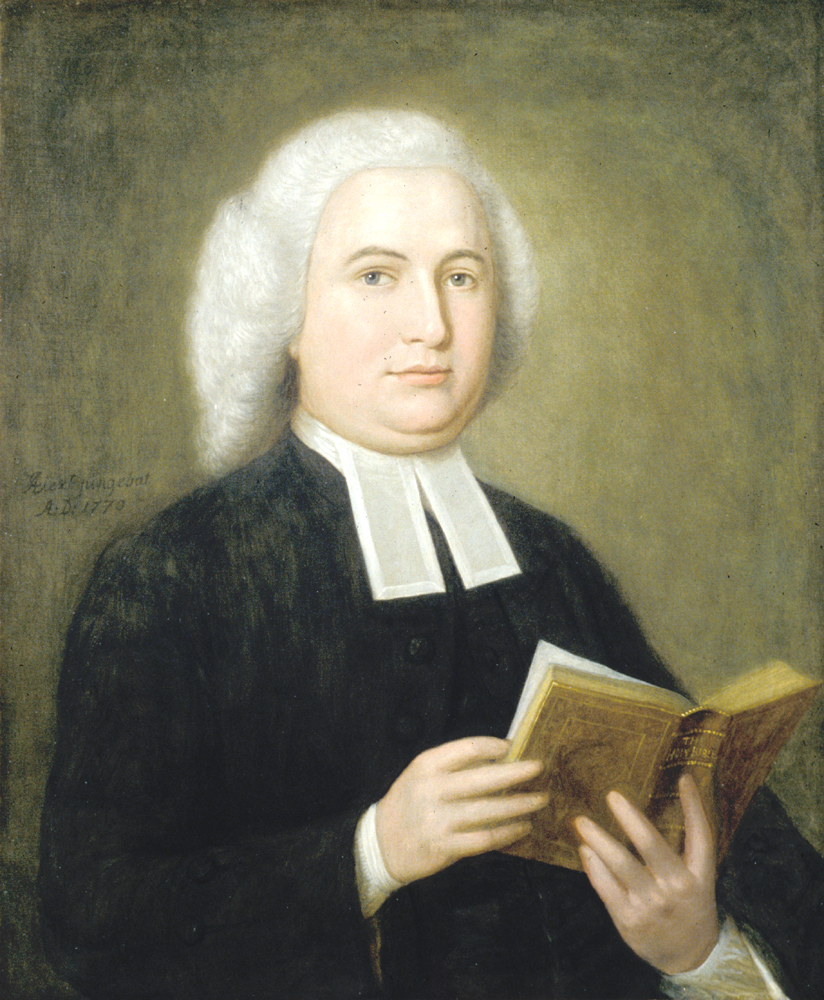

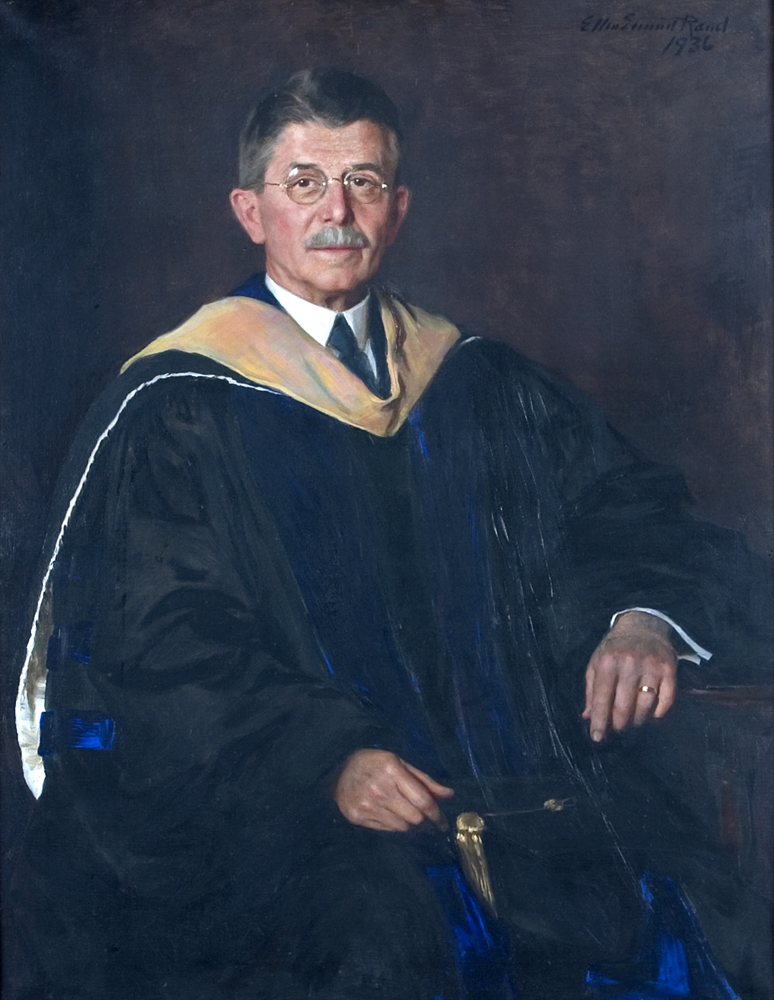

The history of Rhode Island Hall cannot be separated from that of Brown University as a whole, as the building played a pivotal role in the rise in importance of the college. In 1764, a Baptist minister by the name of James Manning (who would later become Brown University’s first president) (Figure 3.01) and the Congregationalist Ezra Stiles founded the College of Rhode Island with the financial support of a number of Rhode Island locals (including John and Nicholas Brown) in the city of Warren on the east side of Narragansett Bay. The diverse backgrounds of its founders and the overall religious tolerance of Rhode Island in general influenced the college to be the first to allow students of any religious affiliation to attend. The college was moved to its current site in Providence in 1770 and was later renamed Brown University in 1804, after Nicholas Brown, Jr. (Figure 3.01) who graduated in 1786 (Mitchell 1993).

Figure 3.01: Portraits of James Manning (left), co-founder and first president of Brown University and Nicholas Brown, Jr. (right), for whom the College of Rhode Island was renamed in 1804 (Emlen 2003) [link]

Figure 3.01: Portraits of James Manning (left), co-founder and first president of Brown University and Nicholas Brown, Jr. (right), for whom the College of Rhode Island was renamed in 1804 (Emlen 2003) [link]

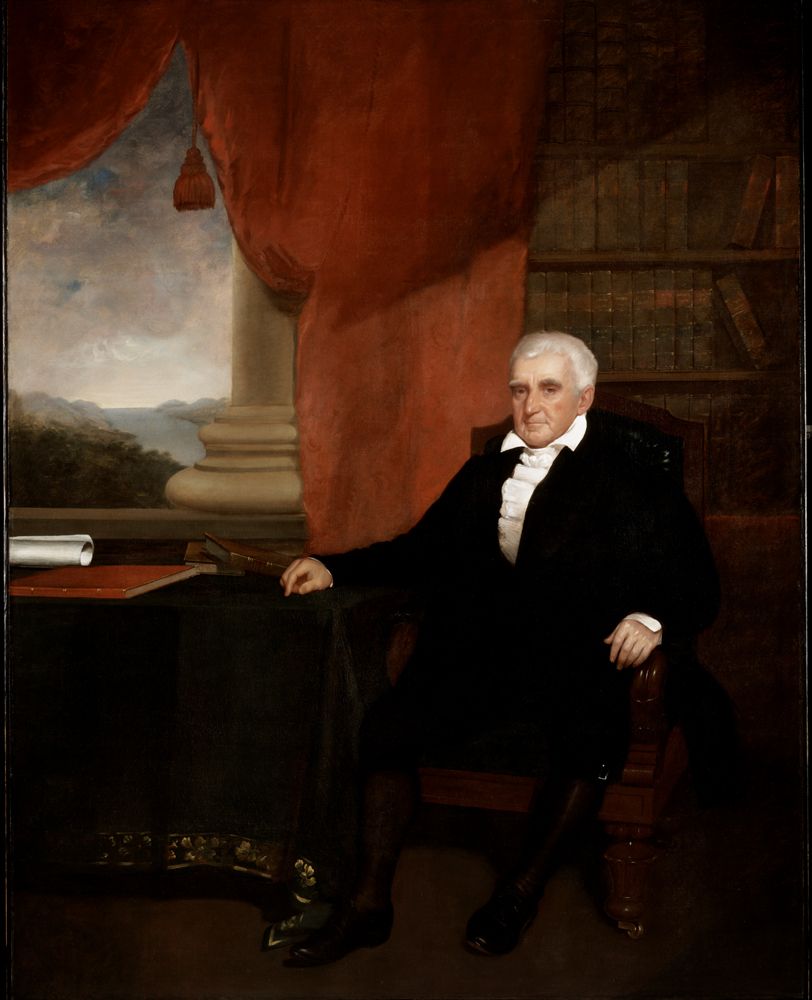

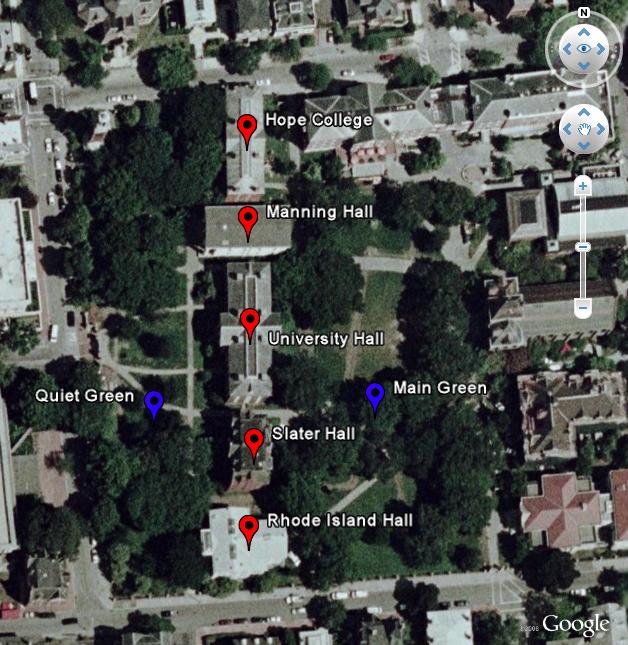

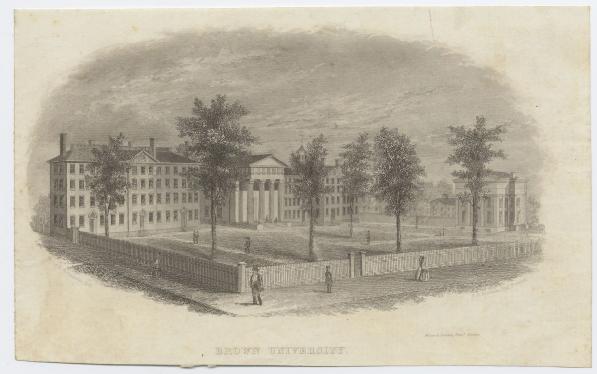

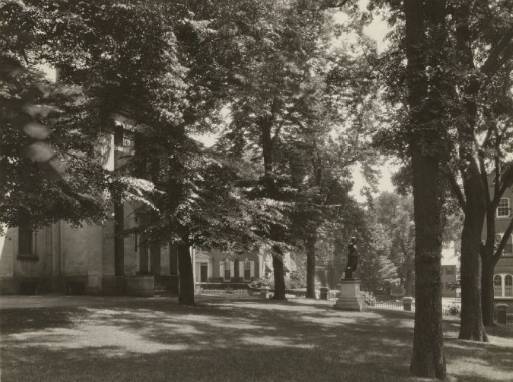

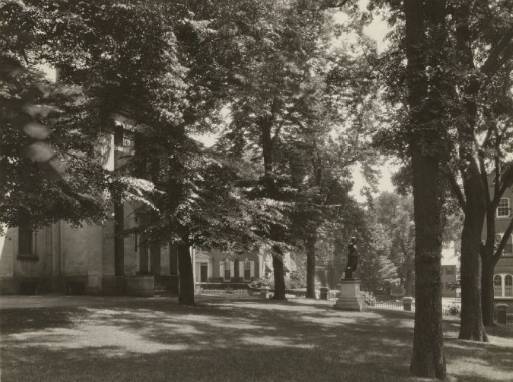

Construction of the first university building commenced immediately after the move to Providence. The College Edifice (Figure 3.02) (later named University Hall in 1822 upon the construction of Hope College) would influence the building landscape of Brown University into the following century, as it stood near the summit of College Hill facing down towards the Providence River where the city had been founded by Roger Williams in 1636 (Mitchell 1993: 550). The next three buildings to be constructed for Brown University, including Rhode Island Hall, would form a north-south line of structures all facing in the same westerly direction (Figures 3.03 and 3.04).

Figure 3.02: The College Edifice, today known as University Hall (Lenehan 2006) [link]

Figure 3.02: The College Edifice, today known as University Hall (Lenehan 2006) [link]

Figure 3.03: The line of campus buildings at the summit of College Hill, from left to right (north to south) – Hope College, Manning Hall, University Hall, Slater Hall, and Rhode Island Hall (barely visible) (Forasté 1995) [link]

Figure 3.03: The line of campus buildings at the summit of College Hill, from left to right (north to south) – Hope College, Manning Hall, University Hall, Slater Hall, and Rhode Island Hall (barely visible) (Forasté 1995) [link]

Figure 3.04: The north-south alignment of Brown University buildings between the Quiet and Main Greens

Figure 3.04: The north-south alignment of Brown University buildings between the Quiet and Main Greens

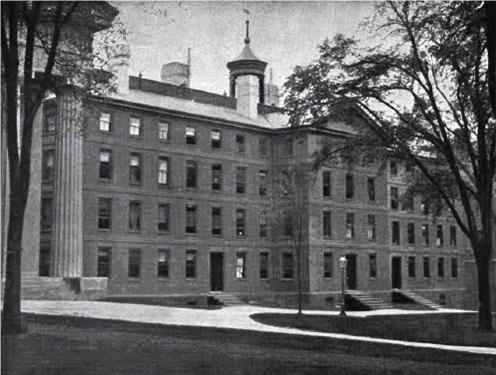

University Hall and Brown’s second building, a dormitory named Hope College, both represented a similar brick colonial architectural style; indeed, one of the initial designs of University Hall recommended that “it be a plain building, the walls of best bricks and lime” (Mitchell 1993: 550). This simplicity seems to have become outdated, as the third campus building, Manning Hall, was designed according to the classical revival style, and at this time in 1834 University Hall was covered with a coat of cement to match Manning Hall (Mitchell 1993: 552) (Figure 3.05). The fact that University Hall was later renovated back into its original state points to the inherent bias in historic preservation to preserve an older history, though both histories are equally valid.

Figure 3.05: After the construction of Manning Hall, University Hall was covered with stucco to suit the classical revival style (Tolman 1894: 108)

Figure 3.05: After the construction of Manning Hall, University Hall was covered with stucco to suit the classical revival style (Tolman 1894: 108)

By the late 1830s and 1840s, University Hall seems to have reached a state similar to that of Rhode Island Hall in 2008. University Hall had declined in importance as the sole building on campus, but it still remained cluttered with rooms for miscellaneous functions. The structure had been used in both the American Revolutionary War of 1776 and the Dorr Rebellion of 1843, causing significant overuse and damage to the building. In addition, the building had been used as a chapel (before Manning Hall became the university chapel), classroom space, offices, and housing for students. According to a contemporary Brown University student, Edward H. Cutler, the upper story of University Hall was known as Pandemonium due to the excessive number of partitions in the hallways meant to create more rooms. These partitions even became known as

“petitions” because students would inscribe their signatures into the wall demanding the partitions’ removal (Mitchell 1993: 553).

As University Hall became more cluttered, plans began to have a new building constructed. Thus, Rhode Island Hall was conceived as a method of salvaging the university from not only a lack of space but from a surfeit of pranksters who went as far as vandalizing university property in hopes of convincing the college to construct more building space. The Corporation convened in 1836 to address the need to build. According to Mitchell (1993: 466), the project progressed slowly due to a lack of funds: after two years only two-thousand five hundred dollars had been raised. Nicholas Brown, Jr. pushed the project along in 1839 after writing a letter in which he presented two lots of land – one on Waterman Street for the president’s house (for which he pledged seven thousand dollars) and another on George Street known as the Hopkins estate for “another College edifice” (for which he pledged three thousand dollars) (Brown 1839). This action was enough to convince a number of others, most of whom were Rhode Island locals, to subscribe more than ten thousand additional dollars by the first of May (Tolman 1894: 133). Thus, the building was named Rhode Island Hall.

The Hopkins estate mentioned in Nicholas Brown’s letter to the treasurer of Brown University may refer to the descendants of Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785) (Figure 3.06), the first Chancellor of the college (Mitchell 1993: 292) and a governor of Rhode Island who had attended the first and second Continental Congresses and signed the Declaration of Independence. Though no record of his owning land near George Street exists, Hopkins built a small house on South Main Street (Figure 3.06) (then known as Town Street) in 1742 (Mitchell 1993: 292). The house can still be visited today, though it was moved to its present location near the Court House on the renamed Hopkins Street in 1809. Providence tour guides still refer to this building as the house in which George Washington stayed when he had occasion to visit Providence. Early sketches of the university focus on University Hall, but previous structures certainly existed on the later site of Rhode Island Hall.

Figure 3.06: Stephen Hopkins (left) (Emlen 2003) and his modest house near South Main Street (right) (Ducke 2008) [link]

Figure 3.06: Stephen Hopkins (left) (Emlen 2003) and his modest house near South Main Street (right) (Ducke 2008) [link]

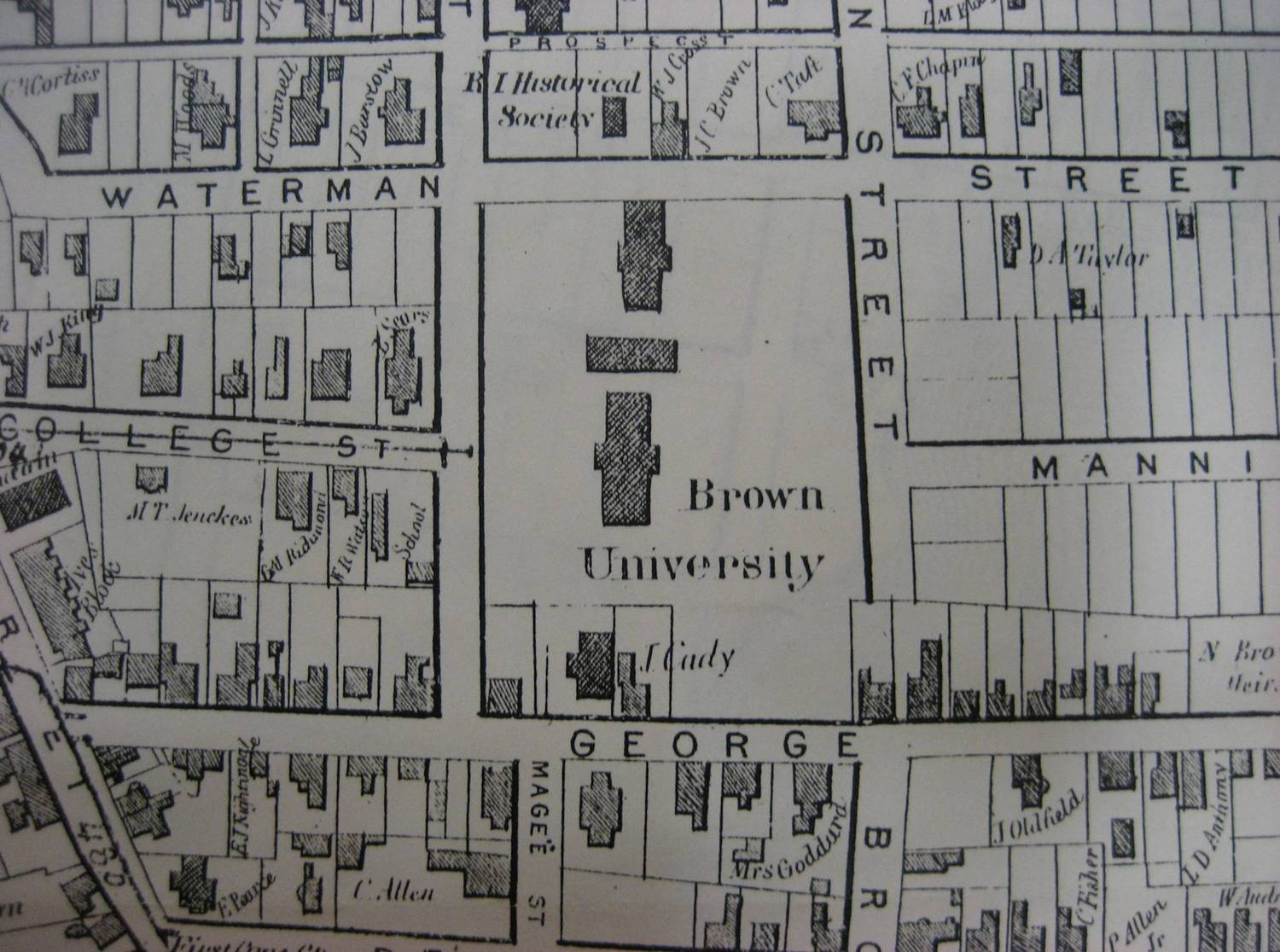

An engraving from 1795 (Figure 3.07) shows the first College Edifice with the President’s house and gardens, but to the very edge of the engraving appears to be a well and a small house. An interesting possibility is that this well is the one that was later rediscovered inside Rhode Island Hall in December of 2008. However, if the scale of the engraving is accurate, this house would seem to be located closer to the later site of Slater Hall. According to Kaitlin Deslatte (2008), three structures existed on the site prior to the construction of Rhode Island Hall, one of which was the Edward Dexter House built between 1795 and 1797 later relocated to 72 Waterman Street, ironically, next-door to the current site of the Joukowsky Institute (Figure 3.09). The relocation of this building in the 19th century is surprising. Why did Brown University not demolish the structure? The owner of the house may have provided subscriptions for the construction of Rhode Island Hall or he may have had enough wealth to pay for the relocation of the house himself. However, conflicting dates have shown some of this information to be incorrect. An 1857 map (Figure 3.08) shows the three structures described by Deslatte, and according to land grants and the Providence Preservation Society (Gowdey 1965, Deslatte 2008), the Dexter House was moved in 1860. This date is twenty years later than the recorded year of construction of Rhode Island Hall. One of the three buildings in the 1857 map, then, must be Rhode Island Hall – it is, in fact, drawn in the same shade as University Hall, Hope College, and Manning Hall. Therefore, the Dexter House remained in its original site, alongside Rhode Island Hall for twenty years.

Another engraving from 1840 (apparently before Rhode Island Hall had been built) shows the proper design of Rhode Island Hall but has positioned the building further west on George Street rather than in line with University Hall (Figure 3.10). According to project manager John Cooke, a foundation was dug in this location, but public outrage over the possibility of an obstructed view of the campus caused a last minute change in location (Cooke 2009). However, Cooke may have confused this story with that of the construction of Slater Hall (Mitchell 1993: 498).

Figure 3.07: A 1795 engraving of Brown University showing the President’s House (left), the College Edifice, and two structures that may have occupied the later site of Rhode Island Hall [link]

Figure 3.07: A 1795 engraving of Brown University showing the President’s House (left), the College Edifice, and two structures that may have occupied the later site of Rhode Island Hall [link]

Figure 3.08: An 1857 map of the city of Providence, showing the shaded buildings of Brown University and the Edward Dexter House (Deslatte 2008)

Figure 3.08: An 1857 map of the city of Providence, showing the shaded buildings of Brown University and the Edward Dexter House (Deslatte 2008)

Figure 3.09: The Edward Dexter House (right) and the current Joukowsky Institute (left) (Deslatte 2008)

Figure 3.09: The Edward Dexter House (right) and the current Joukowsky Institute (left) (Deslatte 2008)

Figure 3.10: An enigmatic 1840 engraving showing an incorrect placement of Rhode Island Hall (Nuding 2008) [link]

Figure 3.10: An enigmatic 1840 engraving showing an incorrect placement of Rhode Island Hall (Nuding 2008) [link]

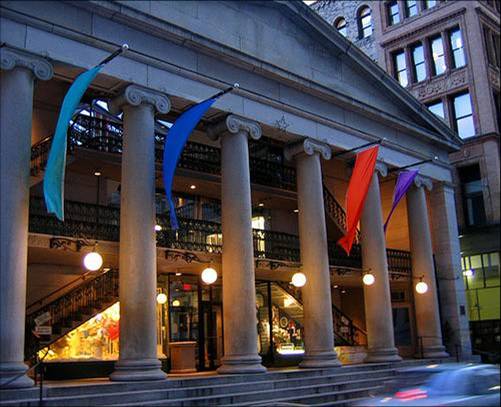

Construction of Rhode Island Hall began in 1840, and the edifice was opened for public inspection on September 3rd of that same year. The builders were William Tallman and James C. Bucklin (Mitchell 1993: 466), who had built Manning Hall and the Arcade in downtown Providence previously. Though Tallman and Bucklin was the name of a contracting firm, James C. Bucklin was also an architect, having designed the Arcade with Russell Warren (Woodward 2003). Bucklin also later designed the former home of the Rhode Island Historical Society (Mitchell 1993: 107), now known as the Cabinet located on 68 Waterman Street (the current location of many Joukowsky Institute lectures) (Figure 3.11). Built in 1842, the Cabinet shows clear similarities with the design of Rhode Island Hall. Tallman and Bucklin, then, were likely both the architects and builders of Rhode Island Hall, as the Mason’s Specifications refer to them as such (Andrews 1839). During the 2008 demolition, a wooden rafter (Figure 3.12) from above the second floor was uncovered, revealing the words “James A. Potter & Co.” An 1892 description of the company reads:

Foot of Crary Street; Office, No. 33 Westminster Street. The pioneer house in Rhode Island engaged in the manufacture and sale of yellow pine lumber is that of James A. Potter & Co. This business was originally founded in 1838 by Mr. James A. Potter … thoroughly identified with the general welfare of the community, and with the lumber interest in particular. Their sawing and planing mill, which is equipped with the latest and most improved machinery, covers an area of nearly three and one half acres, furnishes employment to from twenty to thirty hands, and a very heavy stock of yellow pine lumber, for all purposes known to the trade, is constantly kept on hand … all who open trade negotiations with them are certain to be treated in the most considerate and equitable manner. (Adams et al. 1892: 166)

Thus, Rhode Island Hall must have been one of the company’s first projects, taking place two years after James A. Potter & Co. was established. Today, the site of the company’s mill is likely located underneath Interstate 95.

Figure 3.11: Two buildings designed by James C. Bucklin – The Arcade in Downtown Providence (left) (Nickerson 2007) and the Cabinet, Mencoff Hall (right) [link]

Figure 3.11: Two buildings designed by James C. Bucklin – The Arcade in Downtown Providence (left) (Nickerson 2007) and the Cabinet, Mencoff Hall (right) [link]

Figure 3.12: The James A. Potter & Co. maker’s mark on a wooden beam in the attic of Rhode Island Hall

Figure 3.12: The James A. Potter & Co. maker’s mark on a wooden beam in the attic of Rhode Island Hall

Though the original 1840 plans have been lost, a list of Mason’s Specifications provides some information to reconstruct the design of Rhode Island Hall. According to Mitchell (1993: 466), the original building measured 70 by 42 feet with a projection of 12 by 26 feet. The professors of chemistry and natural philosophy each had their own lecture rooms on the first floor, a collection of minerals and “other objects” was located on the second floor, and a chemical laboratory was situated in the basement. According to the Mason’s Specifications, this basement was divided into four equal sections: two rooms, each with a partition.

The next document to mention Rhode Island Hall dates to the late 1850s, when Rhode Island Secretary of State John Russell Bartlett commissioned the painting of a number of portraits of prominent Rhode Islanders to be “arranged in some suitable hall where at all times they may be accessible” (Emlen 2003). The university had collected portraits of figures associated with the college since 1815 but had not gathered a substantial collection to display in a single place – University Hall and Manning Hall had both been used for such a purpose. In 1857, Rhode Island Hall was designated as a suitable hall for the exhibition of the portrait collection (Emlen 2003). An 1857 article from the Christian Inquirer, a Boston-based Unitarian paper, notes that “some liberal men of Rhode Island have been collecting the portraits of eminent men of that State, which are to be deposited in Rhode Island Hall, Brown University” and suggests that portraits of Newport-native William Ellery Channing and Narragansett Chief Ninigret among others be displayed there (Bellows 1857: 3). The prestige of this portrait collection was known throughout the East Coast, as a copy of the New York Observer and Chronicle dating to July 26, 1860 mentions the completion of a portrait of Reverend Doctor Crocker of Providence, Rhode Island to be placed in Rhode Island Hall (1860: 238). University Librarian Reuben Guild observed in 1867 that

The collection of portraits in Rhode Island Hall now comprises thirty-one, many of them painted from life. They represent men of all ranks and professions, and include not only benefactors, officers, and graduates of the college, but also soldiers, statesmen, and divines, who have distinguished themselves in the annals of Rhode Island. An enterprise so auspiciously begun, should be continued from year to year, until the Collection shall at least approach more nearly to completion. (Emlen 2003)

An undated document from the John Hay Library archive entitled “Portraits in Rhode Island Hall” lists thirty-four portraits, and Bronson (1914) writes that the collection contained thirty-five portraits in 1869. However, the thirty-fourth portrait on the list is that of Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, acquired in 1863, according to current University Curator Robert Emlen (2003). Perhaps some of the portraits were moved out of Rhode Island Hall between 1863 and 1867, or some of the dates of acquisition of portraits are incorrect.

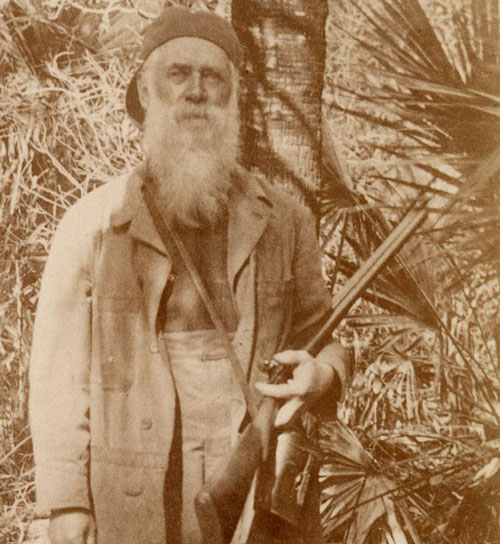

Portraits, display cases, lecture halls, a laboratory – Rhode Island Hall had already become a cluttered space by the late 1860s (Figure 3.13). To address the need for more capacity, plans for an addition on the eastern side of the building were drafted in 1873. This addition was completed in 1874. The new space was used partly for the display of the portrait collection, which was moved to the second floor of the addition in 1875, and glass cases were also added to this floor for use in the Museum of Natural History (Mitchell 1993). Though a “museum” had existed on campus as early as 1790, President Alexis Caswell had requested the establishment of a proper museum in 1869; however, funds were lacking. Professor John Whipple Potter Jenks (Figure 3.14) who taught a volunteer taxidermy class in the basement of Rhode Island Hall offered to fill the museum cases himself by shooting birds and small mammals, and even worked for the United States Fish Commission without pay to gather marine specimens.

Figure 3.13: An 1868 photograph of the Museum of Natural History and the portrait collection in Rhode Island Hall (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.13: An 1868 photograph of the Museum of Natural History and the portrait collection in Rhode Island Hall (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.14: Professor J.W.P. Jenks, curator of the Museum of Natural History, in the field (Nuding 2008) [link]

Figure 3.14: Professor J.W.P. Jenks, curator of the Museum of Natural History, in the field (Nuding 2008) [link]

J.W.P. Jenks was certainly one of Brown University’s most eccentric professors. Born in 1819 to parents Nicholas and Betsey Potter Jenks, J.W.P. Jenks was descended from John Potter, who served with George Washington during the Revolutionary War at Valley Forge (Lyman et al. 1909: 22) but was probably not related to the James A. Potter who supplied the yellow pine for the construction of Rhode Island Hall (Cutter 1914: 1313). Nevertheless, J.W.P. Jenks seems to have had a magnetic attraction to the building and the museum housed within. Two years before the construction of Rhode Island Hall, Jenks graduated from Brown University with the class of 1838. After a brief period of teaching in Georgia, Jenks returned to New England after marrying Sarah Tucker of a wealthy Massachusetts family. Though Jenks considered becoming a missionary, his father-in-law appointed him as principal of the then failing Peirce Academy in Middleboro, Massachusetts. From 1848 to 1871, Jenks greatly improved the academy’s quality of education, after which in 1872 he returned to Brown University as the curator of the museum in Rhode Island Hall (Mitchell 1993: 308-309, Lyman et al. 1909: 22).

Jenks employed the same effort in increasing the importance of Rhode Island Hall in relation to Brown University’s campus as he had in improving the Peirce Academy a few decades before. Not only did Jenks volunteer as professor of the taxidermy class (Figure 3.15), but he also donated his collections to the museum and used his own expenses to design the museum’s interior. Jenks’ dedication to his work is evident in his traveling weekly to the university from his home in Middleboro, Massachusetts, his working 16 hours a day (stuffing animals for the museum as late as 11 PM), and his sleeping in University Hall (Mitchell 1993: 308-309). Jenks even taught a course in agricultural zoology after the passing of the Morrill Act, which specified that any educational institution receiving land grants from the Federal Government was required to hold a course in agriculture, a subject of which Jenks apparently knew little (Mitchell 1993: 309). Jenks’ hard work finally took its toll when, on September 26, 1894, he collapsed on the steps of Rhode Island Hall:

He was in his seventy-sixth year, apparently hale and hearty, his youthful enthusiasm not abated. He had lunched, perhaps too heavily, with some dear friends with one of whom he walked up College Hill, stopped for a minute in conversation on the steps of Rhode Island Hall, started to go upstairs to the Museum, sank down and expired without a moment’s sickness or suffering. One could not ask for a finer end. Walter Lee Munro (Mitchell 1993: 309)

Figure 3.15: Professor J.W.P. Jenks; Dallas Lore Sharp, grandfather of Martha Sharp Joukowsky; and the taxidermy class from ca. 1891-1895 (Nuding 2008) [link]

Figure 3.15: Professor J.W.P. Jenks; Dallas Lore Sharp, grandfather of Martha Sharp Joukowsky; and the taxidermy class from ca. 1891-1895 (Nuding 2008) [link]

A report from President Andrews in 1892 notes the educational values of the Museum of Natural History, composed of the Jenks Museum of Zoology and the Museum of Anthropology (Professor Alpheus S. Packard taught courses in anthropology beginning in 1891) (Mitchell 1993: 28), as well as Jenks’ personal efforts to maintain Rhode Island Hall’s natural history museum. Despite this report, after Jenks’ death the building seems to have begun to decline in importance. By the late 19th century, Rhode Island Hall continued to be crowded, as the needs of an ever growing university increased. The number of display cases in the Museum had surpassed the building’s capacity, obstructing windows. By 1885, the last of the Rhode Island Hall portraits were relocated primarily to Sayles Hall, where they remain today (Figure 3.19). Alpheus Spring Packard, professor of zoology and geology, was pleased with this decision as the move provided more space for the biology laboratories in Rhode Island Hall.

Indeed, Brown University as a whole seems to have been a densely packed space at this time. Even after the construction of Rhode Island Hall and later Robinson Hall (Brown University’s first library) in 1878, the Corporation decided that the university’s first edifice, University Hall, remained crowded, and renovation began in 1883 with extra funds from the construction of Slater Hall, which had taken place in 1879. This renovation provides an insight into the climate surrounding preservation at the time:

it would be far better to expend this sum in the erection of a new hall than in repairing the present dilapidated structure … The fact that it is a relic of the past, and endeared by many pleasant associations may be an argument for allowing it to stand, in the opinion of antiquarians and graduates of fifty years ago, but can have but little weight to the rising generation of students who know the discomfort of rooming within its hoary walls. The Brunonian (Mitchell 1993: 553)

To some students of the Brown community in the late 1800s, historic buildings were not worth preserving. Though the idea of demolishing a one-hundred-year-old historic structure may seem preposterous today, this same issue still applies in many contemporary situations. In December of 2008, the historic Louttit Laundry facility on Cranston Street in Providence was demolished. Built in 1906, the building had been abandoned since 1987 and appeared on the Providence Preservation Society’s Ten Most Endangered Places list three times (Hogue 2008). Too often demolition of an historic structure becomes more appealing than renovation. Fortunately, for Brown University and preservationists, University Hall was deemed worthy of standing, though a solution to Rhode Island Hall’s dilemma remained to be found.

Even after the installation of skylights in the summer of 1886 and an addition in 1904 on the south side of the building allowing live animals to be moved from an outside lean-to into the ground floor as well as creating space for an aquarium on the second floor and a room for preparing animal skeletons on the third, Rhode Island Hall remained crowded, and display cases began to be removed from the building. By 1905, professor of biology Albert Mead (Figure 3.16), struggling to maintain the museum, appealed for one thousand dollars for the maintenance of the exhibits, though he seems to have done so reluctantly:

the reasonableness of spending money for the dusting and rearranging of the miscellaneous curios of a university junk shop for the gratification of a few straggling sightseers is, we readily admit, not obvious. (Mitchell 1993: 398)

Figure 3.16: Professor of Biology Albert Davis Mead (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.16: Professor of Biology Albert Davis Mead (Emlen 2003)

A destructive fire of unknown cause sealed the fate of the Museum of Natural History in 1906, burning many of the display cases from the basement to the attic. An article from the University Archives describes the scene at Rhode Island Hall. According to the article, the fire ignited in the basement at 1:15 in the morning and quickly rose above to the attic. The building would have likely been destroyed had two graduate students (Philip Hadley and Victor Emmel), whose room was adjacent to the museum, and the night watchman (Archibald Cameron) not reacted swiftly with fire extinguishers before the arrival of the firemen. The article mentions that retired professor of zoology Alpheus S. Packard’s library had been removed from the building according to his will and that classmen with “towel-protected faces” were able to save many of the expensive pieces of apparatus. However, the laboratory and museum were most damaged due to the advancement of the fire behind the wooden sheathing of the west wall. Indeed, the firemen were forced to rip out this wall in “huge chunks” in order to extinguish the flames. Though the fire destroyed an irreplaceable collection, the University was almost relieved of the fortuitous solution to their dilemma:

The requirements of the museum were met in an unexpected and unintentional manner – during the spring term a fire, starting in the basement and almost immediately breaking out in the walls at the top of the building, scorched or burned much of the material in the museum cases and in the attic. [...] This was not an unmitigated calamity. It solved many perplexing questions [...] The central cases have been removed to the rooms of the geological department, the respectable and semi-respectable specimens have been cleaned up and many minor improvements carried out. (Mitchell 1993: 398)

After the fire of 1906, the specimens in the cases were moved to the attic or basement of Rhode Island Hall, the attic of Van Wickle Hall (the former administration building that was razed for the construction of the Rockefeller Library), or the nearby Robinson Hall and Arnold

Laboratory buildings. When Professor J. Walter Wilson (Figure 3.17) became the new chairman of the Biology Department in 1945, he requested permission to discard the material or donate it to the natural history museum in Roger Williams Park. Though some items were donated to Roger Williams Park, the University finally gave Wilson permission to store the items elsewhere on University property if he found a suitable place. The suitable place was a dump on the Seekonk River, “where 92 truckloads of stuffed birds and animals, reptiles, and bones were conveyed” (Mitchell 1993: 398).

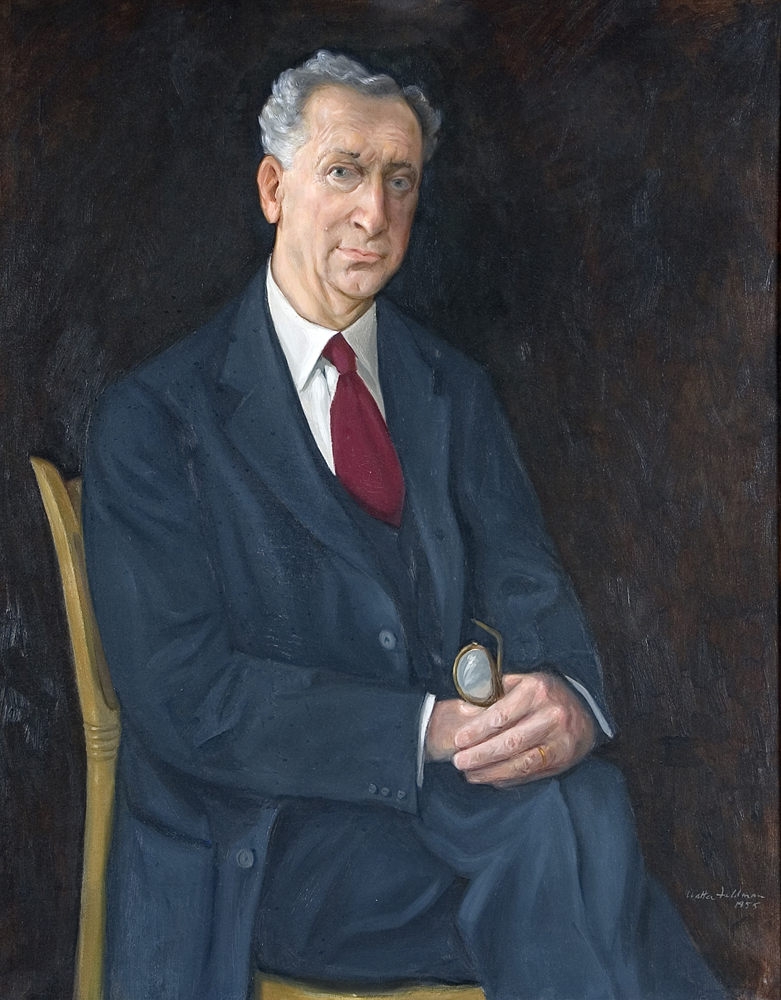

Figure 3.17: James Walter Wilson, chairman of the Department of Biology from 1945 to 1960 (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.17: James Walter Wilson, chairman of the Department of Biology from 1945 to 1960 (Emlen 2003)

Press clippings dating to the period from 1869, when the Museum of Natural History was placed in Rhode Island Hall, to 1945, when the last of the display cases were removed, occasionally describe some of the unique objects that were displayed in Rhode Island Hall. The December 8th, 1870 edition of the Boston Daily Advertiser describes the testing of an electrical machine in Rhode Island Hall:

A few days since the faculty of Brown University and a few friends assembled in Rhode Island Hall, to witness experiments with the Holtz electrical machine recently purchased by the university of Mr. Benjamins, of New York, for whom it was expressly made in Berlin. This machine, which was invented in 1865, produces electricity by induction instead of friction. The one exhibited is the largest in the world, having a thirty inch plate, and is capable of producing a fifteen inch spark, while the largest friction machines can produce but a three inch spark under the same circumstances as this will one of twelve inches. Thus it will be seen that this machine has by far the greater power of tension and almost unlimited power for experiment. The machine was exhibited and explained by Professor Blake Hazard, professor of physics, and notwithstanding the unfavorable state of the atmosphere for electrical tests, gave excellent examples, in various beautiful experiments, of its power, with much satisfaction to the audience. Boston Daily Advertiser December 8, 1870

Though the article mentions a Professor Blake Hazard, which would be a prime pseudonym for a professor engaging in hazardous electrical tests, no professor of physics by that name ever taught at Brown University. The article has likely confused two prominent Rhode Islanders – Rowland Gibson Hazard (1801-1888) and Professor Eli Whitney Blake (1836-1895) (Figure 3.18). Rowland G. Hazard was born to a Quaker family in South Kingston, Rhode Island and actually never received a college degree. Hazard was a staunch abolitionist and was known to operate his family’s textile empire in Peace Dale, Rhode Island, known as the only mill town in America not poisoned by labor unrest. Hazard also became a controversial figure in 1841 when he aided an African-American Rhode Islander who was being held on a New Orleans chain gang. Hazard became affiliated with Brown University when he endowed the Hazard Professorship of Physics (Mitchell 1993: 438).

Professor Blake, on the other hand, arrived at Brown University in 1870, along with the aforementioned Holtz Electrical Machine. He was also named the first Hazard Professor of Physics at Brown University in that same year (Mitchell 1993: 75). Professor Blake additionally played a major role in the development of the telephone, along with Professor John Peirce, Dr. William F. Channing, (the son of Reverend William Ellery Channing), and Brown University students James Earle, John Greene, and William Ely. When Alexander Graham Bell heard of his competition, he was annoyed by “the experimenters,” though the group of Brown scientists was less concerned with commercial profit than scientific progress. In 1877, Professor Blake and William Ely performed a demonstration of the telephone at Rowland Hazard’s home at 45 Williams Street:

The wire was strung between the reception room, just within the front door, and the study at the other end of the long hall, with a telephone at either end. Ely happened to be listening at the receiver in the study, where Prof. Blake was completing his preparation, when he heard a familiar voice at the other end of the wire and said “My father has just come in, I hear his voice; were you expecting him?” Prof. Blake was dumbfounded and elated, for not even in their wildest flights of fancy had the scientists dreamed of the possibility of recognizing individual voices. Walter Lee Munro (Mitchell 1993: 438)

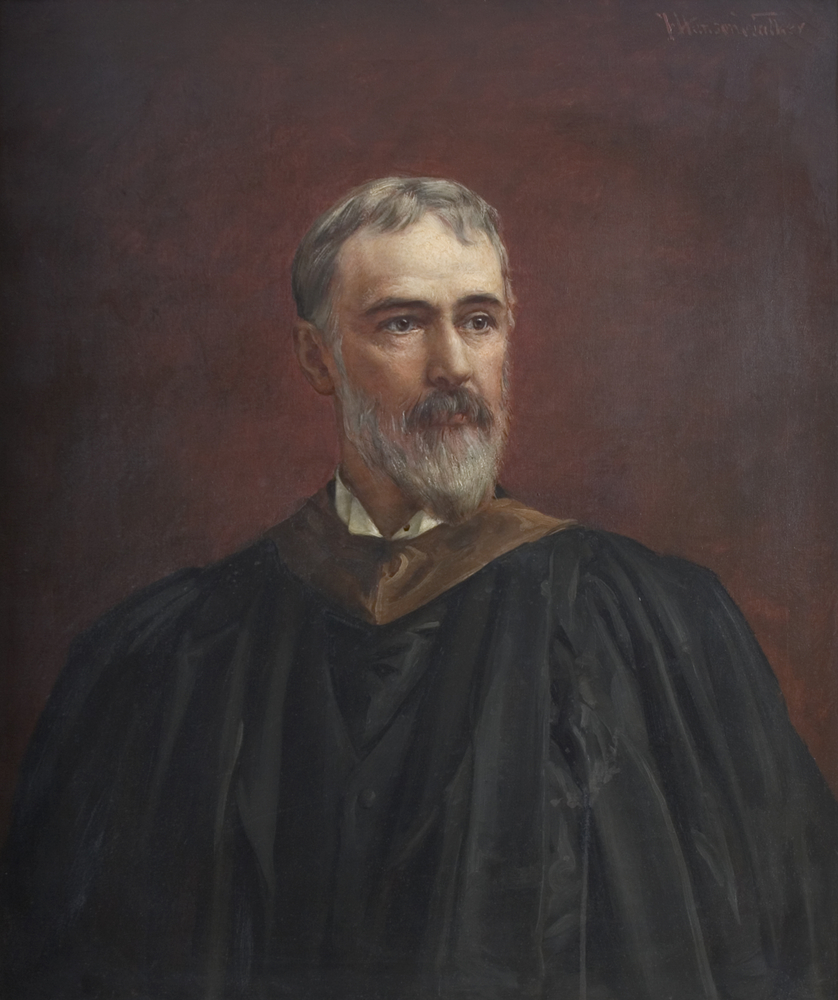

Figure 3.18: Prominent Rhode Islander Rowland Gibson Hazard (left) and the first Hazard Professor of Physics, Eli Whitney Blake (right) (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.18: Prominent Rhode Islander Rowland Gibson Hazard (left) and the first Hazard Professor of Physics, Eli Whitney Blake (right) (Emlen 2003)

The Museum of Natural History held such interesting specimens that even the New York Times mentions an enigmatic display. An article from August 15, 1885 reports on a “pet superstition among Block Islanders.” The spirit is described as an “eerie blaze” lasting fifteen minutes that appeared during an easterly storm. As the story goes, a ship known as the Palatine was bound for Philadelphia in 1752, carrying emigrants from Holland. During the passage, a mutiny occurred, and the captain was killed. The first mate and crew proceeded to starve the passengers and plundered their belongings. The ship was forced to dock at Block Island due to a strong winter storm. The Palatine was then plundered once again, this time by the settlers on the island, who eventually burned the ship to hide the traces of their looting. However, one woman passenger refused to leave her belongings, and she was burned with the ship. Ever since, a strange light has appeared at night before dark, easterly storms. The Dickens Family of Block Island donated a “mortar made from a lignum vitae block” of wood from the Palatine to Brown University, known as the “Dancing Mortar” because “it performed such fantastic freaks”:

The mortar was fashioned by the islanders for grinding corn. It is 14 inches high by 10 inches in diameter and holds four quarts. On the oaken floor of the old Dickens kitchen before the hearth it would suddenly tumble over on its side, and rolling out into the apartment it would set itself up and break into a gentle heel-and-toe polka. Warming up with the excitement its movements would quicken, and higher and higher it would bound until it reached the rafters overhead. Then it would remain passive sometimes for weeks and months together. (NYT 1885)

Though the article dismisses the ghost story and the eerie light as an insular legend that can be scientifically explained by a gas that rises from the bottom of the ocean and ignites under certain conditions, no explanation is provided for the mysterious Dancing Mortar on display at Rhode Island Hall.

Oddly, a Lowell, MA paper dating to Halloween of 1959 (well after the last of the display cases were removed from Rhode Island Hall) describes the returning of “Benign Souls” in New

England (Cameron 1959). The article mentions the Dancing Mortar of Block Island, which “inexplicably rolled about and at times flung itself high into the room” (Cameron 1959). Apparently, as recently as the late fifties, it could still be seen in Rhode Island Hall.

Though Rhode Island Hall certainly was (and is) a unique building, clutter was common in many campus buildings, including University Hall. However, Rhode Island Hall seems different in that its function changed so often, and, in fact, a definite use for the building never seemed to be determined. In 1836, when the Corporation decided to provide funds for the construction of a building dedicated to the sciences, science was seen as a single subject, whereas over time, the field of scientific research diversified into subjects that could no longer be housed in a single building. Though Rhode Island Hall was deemed as the building to house the sciences, it was also a museum, so objects seemingly unrelated to the sciences (portraits, for instance) also were thought to belong.

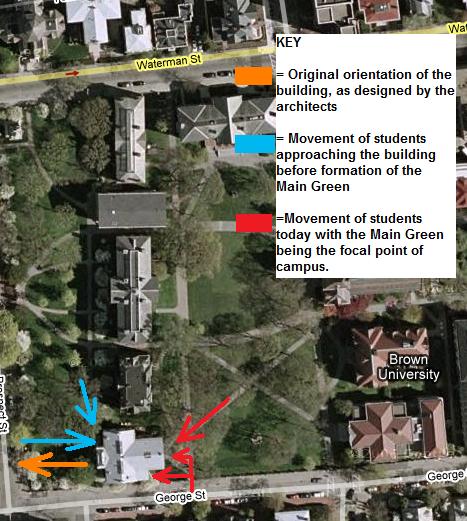

The diminishing importance of Rhode Island Hall could also be attributed to the construction of Sayles Hall in 1881, a defining moment in not only the history of Rhode Island Hall but also the campus orientation from that time on. As Nuding (2008) observes “today many people experience Rhode Island Hall backwards” (Figure 3.20). When constructed in 1840, Rhode Island Hall was designed to overlook the city of Providence, along with the three university buildings that preceded it (Figure 3.03). Early engravings are all oriented to the west of campus facing towards University Hall and the space between Rhode Island Hall and Prospect Street, known by students as the Quiet Green (Figures 3.07). The monumental columns and the façade of Manning Hall are located on its west side, not the building’s east side facing the Main Green (the space between University Hall and Sayles Hall). In addition, an 1840 engraving reveals the original plan for the position of Rhode Island Hall further west (Figure 3.10). Had this location become the site for Rhode Island Hall, other buildings would have likely been constructed surrounding the Quiet Green, and this space likely would have become the central green space on campus. Indeed, when Slater Hall was in its planning stages, a foundation had already been dug just west of Rhode Island Hall on George Street. However, when news of the planned position of the new university building had spread, influential inhabitants protested that their view of campus might be obscured. According to the Providence Journal, “it was a matter of surprise and regret that grounds upon which so many are accustomed to gaze while taking daily walks are to be disfigured by the march of events” (Mitchell 1993). At the last minute, the university altered the location, as well as the dimensions of the new building, so as to squeeze Slater Hall between University Hall and Rhode Island Hall. Upon the construction of Sayles Hall, a new open area had been created (the Main Green), and the focus of the campus had shifted further east.

Figure 3.19: The portrait collection in Sayles Hall, ca. 1881 – note the absence of the Hutchings-Votey organ, donated to Brown University in 1903 (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.19: The portrait collection in Sayles Hall, ca. 1881 – note the absence of the Hutchings-Votey organ, donated to Brown University in 1903 (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.20: Changes in orientation of and access into Rhode Island Hall that began to take place when the Main Green became the center of campus (Nuding 2008)

Figure 3.20: Changes in orientation of and access into Rhode Island Hall that began to take place when the Main Green became the center of campus (Nuding 2008)

However, Rhode Island Hall was still accessed from the west entrance for some time after the construction of Sayles Hall, due to the placement of a replica of the Augustus Prima Porta in front of Rhode Island Hall on the Quiet Green (Figure 3.21). Given to Brown University in 1854 as a gift from Moses Brown Ives Goddard, the bronze statue was not unveiled until September of 1906. Caesar Augustus stood in front of Rhode Island Hall even through the hurricane of 1938, when it first lost its right arm. Though the arm was replaced, it was soon lost again, due to the number of hazardous trees surrounding the Quiet Green (Mitchell 1993, Nuding 2008). In 1952, the statue was relocated to its current position in front of the Sharpe Refectory on Wriston Quad, a more protected site with notably fewer trees. By then the Main Green certainly had become the center of campus, and access to Rhode Island Hall from the east side likely became more common.

Figure 3.21: The Augustus Prima Porta replica in front (west) of Rhode Island Hall (Nuding 2008)

Figure 3.21: The Augustus Prima Porta replica in front (west) of Rhode Island Hall (Nuding 2008)

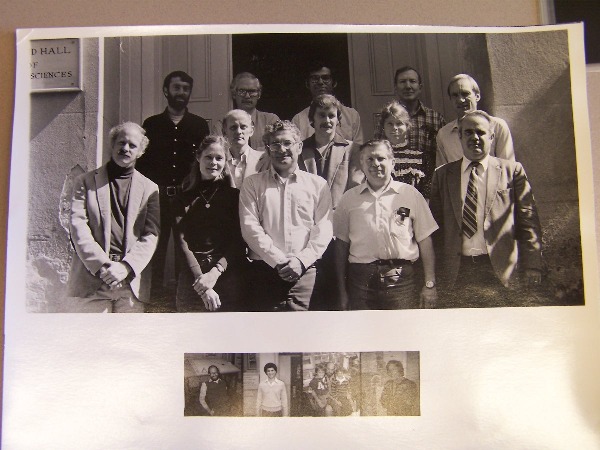

After the construction of Arnold Laboratory in 1915, Rhode Island Hall became the home of the Philosophy Department. Later, in 1964, the Geology Department (Figure 3.22) occupied the basement and second floors, as well as the Lincoln Field Building. The history of the Geology Department is interesting in its own right, as the department was not given its own state-of-the-art building until 1982, though the department had existed since 1836. Nuding (2009) recognized that many of the professors who once taught geology in Rhode Island Hall may still be affiliated with Brown University, and indeed, Professors Jan Tullis, Terry Tullis, and Jim Head shared their memories with Nuding. The resulting study (Nuding 2009) on the memories of Rhode Island Hall provides an interesting example of a form of archaeology that is neither recorded in historical documents nor material remains. Most of the memories surrounding Rhode Island Hall’s one hundred sixty-nine years have been lost, never to be recovered, but many more will surely be created, as long as Rhode Island Hall stands.

Figure 3.22: A photograph of the geology faculty in front of Rhode Island Hall during the 1970s (Nuding 2009)

Figure 3.22: A photograph of the geology faculty in front of Rhode Island Hall during the 1970s (Nuding 2009)

Back to Table of Contents

Back to

Chapter 2: Themes

Continue to

Chapter 4: Rhode Island Hall on the Verge of Renovation

Figure 3.07: A 1795 engraving of Brown University showing the President’s House (left), the College Edifice, and two structures that may have occupied the later site of Rhode Island Hall [link]

Figure 3.07: A 1795 engraving of Brown University showing the President’s House (left), the College Edifice, and two structures that may have occupied the later site of Rhode Island Hall [link]

Figure 3.13: An 1868 photograph of the Museum of Natural History and the portrait collection in Rhode Island Hall (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.13: An 1868 photograph of the Museum of Natural History and the portrait collection in Rhode Island Hall (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.19: The portrait collection in Sayles Hall, ca. 1881 – note the absence of the Hutchings-Votey organ, donated to Brown University in 1903 (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.19: The portrait collection in Sayles Hall, ca. 1881 – note the absence of the Hutchings-Votey organ, donated to Brown University in 1903 (Emlen 2003)

Figure 3.21: The Augustus Prima Porta replica in front (west) of Rhode Island Hall (Nuding 2008)

After the construction of Arnold Laboratory in 1915, Rhode Island Hall became the home of the Philosophy Department. Later, in 1964, the Geology Department (Figure 3.22) occupied the basement and second floors, as well as the Lincoln Field Building. The history of the Geology Department is interesting in its own right, as the department was not given its own state-of-the-art building until 1982, though the department had existed since 1836. Nuding (2009) recognized that many of the professors who once taught geology in Rhode Island Hall may still be affiliated with Brown University, and indeed, Professors Jan Tullis, Terry Tullis, and Jim Head shared their memories with Nuding. The resulting study (Nuding 2009) on the memories of Rhode Island Hall provides an interesting example of a form of archaeology that is neither recorded in historical documents nor material remains. Most of the memories surrounding Rhode Island Hall’s one hundred sixty-nine years have been lost, never to be recovered, but many more will surely be created, as long as Rhode Island Hall stands.

Figure 3.21: The Augustus Prima Porta replica in front (west) of Rhode Island Hall (Nuding 2008)

After the construction of Arnold Laboratory in 1915, Rhode Island Hall became the home of the Philosophy Department. Later, in 1964, the Geology Department (Figure 3.22) occupied the basement and second floors, as well as the Lincoln Field Building. The history of the Geology Department is interesting in its own right, as the department was not given its own state-of-the-art building until 1982, though the department had existed since 1836. Nuding (2009) recognized that many of the professors who once taught geology in Rhode Island Hall may still be affiliated with Brown University, and indeed, Professors Jan Tullis, Terry Tullis, and Jim Head shared their memories with Nuding. The resulting study (Nuding 2009) on the memories of Rhode Island Hall provides an interesting example of a form of archaeology that is neither recorded in historical documents nor material remains. Most of the memories surrounding Rhode Island Hall’s one hundred sixty-nine years have been lost, never to be recovered, but many more will surely be created, as long as Rhode Island Hall stands.