In an effort to synthesize some of the possibilities of the Dynamic Skyscraper as a building type, I turn to the work of Ken Yeang, a Malaysian architect, who is responsible for some of the most fascinating skyscrapers and skyscraper theories today. Key to Yeang's theories are transforming traditional urban spatial arrangements so that they are vertical and housed within a skyscraper. In his plans, the typical elements of a downtown area (government activities, a central business district, residential areas, arts and greenspaces) would be housed in one building. Instead of homogeneous, repetitive floors within skyscrapers, that do not reference or even realize the presence of anything else within the building, Yeang seeks to create ecologically-friendly skyscrapers with interesting, varied floorplans that facilitate easy movement. To Yeang, the skyscraper is so massive and complex that it can't be understand only in terms of building design, but must also take into account urban design.

(Yeang's Menara Mesiniaga, near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia)

Vertical landscaping is employed in many of Yeang's buildings. Just as an urban park would be an island of refuge in a densely packed city, Yeang designs multi-level atriums, which open up the building to bring in sun and fresh air and promote human-human interactions. These atriums also act as natural ventilation, cutting down on heating and cooling costs, and also act as wind breaks, cutting down on the wind load of the building. Another ecological tactic of his is to have solar shields on the sides of buildings; he points to the animal-world example of anthills with built overhangs to keep them cool as an inspiration for this choice (1).

Yeang's theories also reinvent movement within the skyscraper. Many of his designs employ ramps, allowing people to pass through a skyscraper as they might walk down a sidewalk in a horizontal city. He envisions floors where elevators transfer, like bus transfers, with sets of elevators serving the different functions and parts of the building. Instead of arriving at work, entering an elevator, exiting into an office, and then reversing the process at the end of the day, the intended movement within Yeang's plans is dynamic; the building's inhabitants would be aware of their surroundings because of their constant movement through them (2).

Yeang's writing is full of biological references and analogies, and he clearly embraces the cyborg theory so often discussed in 13 things:

- “...(skyscrapers are) no longer building design, but urban design...Everything in nature is a combination of the biotic and the abiotic. Look at what we build as human beings… everything (in a typical building) is inorganic except you and me and the bugs!" (3)

Yeang is just one player in the burgeoning global network of skyscrapers and their design. The limits of the Dynamic Skyscraper will continue to be tested. I hope this project will encourage everyone - and especially skyscraper buffs - to go out and revisit and rethink the buildings that surround us, and to keep their eyes open to new skyscrapers coming their way. I leave you with a few exciting views into the future of the skyscraper, all from the city of Dubai:

Burj Dubai (planned to be the tallest in the world)

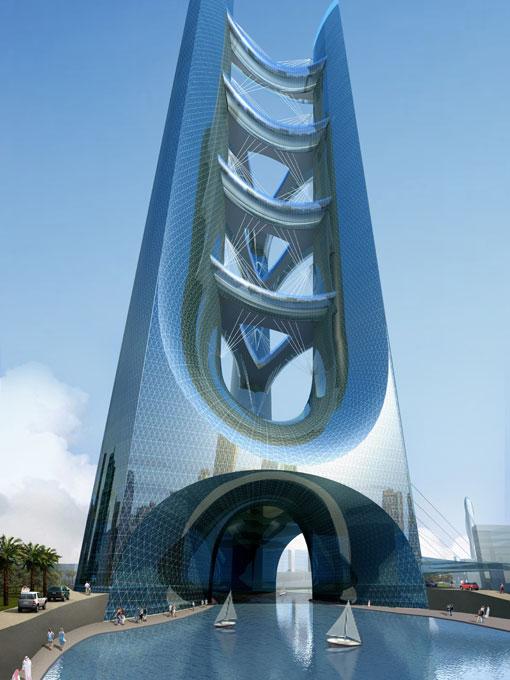

Dubai Towers

Atrium City towers (note the skybridges as another form of inter-building mobility)

Footnotes:

1. Yeang, Ken. The Skyscraper Bioclimatically Considered : A Design Primer . London: Academy Eds., 1996.

2. Yeang.

3. "e-Oculus Email Newsletter." Eye of New York Architecture. 1 May 2007. AIA New York Chapter. 12 Dec 2008 <http://www.aiany.org/eOCULUS/2007/2007-05-01.html>.

back to Making Skyscrapers Move