"A Nkisi that lacks medicine is dead and has no art," MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture.

Certain Minkisi have been appearing on the art market. How does this change in relationship affect the function of the nkisi? Does it simply become a statue when it rests on someone's mantlepiece, or does it retain its function to a certain extent, as that function is built into its materiality?

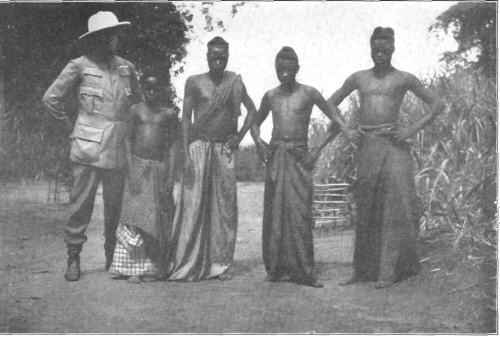

Basically, how does a Nkisi in this context:

differ from a Nkisi in this context?

Or are they even comparable?

Minkisi were never intended to be art. They challenge the entire Western conception of art, which privileges works that have no pragmatic value. They were created for what they can do, but are also fascinating due to their visual appeal. Much of the figurines on display today have become just art-- devoid of their medicine bag and social context, they are no longer an empty container for spirits. They remain a visual effect, but do not have ritual, song and dance to confirm its function. Furthermore, after a ritual, an Nkisi has a specific basket to rest in, in a specific house. When unused by humans, does the Nkisi remain an Nkisi, or does it become a piece of unusual sculpture one can admire through a glass case? Are these necessarily mutually exclusive?

However, when an unknowing viewer looks at an Nkisi, he or she cannot solely be looking upon an object. That object has been created through complex social relationships, time and space. These relationships are not purely symbolic- without them, the Nkisi would not exist. The Nkisi in a museum, as described by Alfred Gell is "the visible knot which ties together an invisible skein of relations." He argues that no single piece of artwork is but that. Rather, it brings with it lineage, history, tribes and people. Every piece of art is, therefore, a manifestation of culture of itself. Even the aesthetic style cannot be separated from culture, according to Gell, because "culture is style, really."

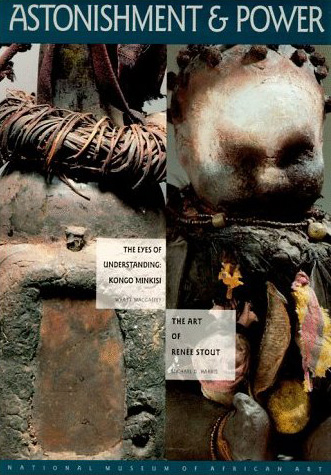

Renee Stout is an Aftrican- American artist who specializes in the creation of Minkisi. I wrote to her asking about how she navigates the paradox between their intended function and their contemporary artistic value.

"I could say that my process of creating has been simultaneously for aesthetic and spiritual results. I suppose that my Minkisi-inspired works do function for me in the way that those original Minkisi functioned for the communities that needed and utilized them. No matter which Minkisi groups we are talking about they were all intended to harness spiritual energy to affect change. It is my hope as I am creating, that my work functions in this way. They certainly help me to focus MY spiritual energy and work through issues that concern me.

As far as the Minkisi in Museums, I do feel that they lose some of their original power when they are taken out of context the same way a church loses some of its power when it has no congregation. Communal energy and the act of ritual is what contributes to the power of both Minkisi and church. However, with out the congregation the church may still stand as a beautiful piece of architecture just as I find the Minkisi to be beautiful forms even outside of their original context. First, the form was made by the hands of an inspired artist, so that in itself brings with it a certain kind of energy that the Minkisi will always contain. Second, and this is my opinion , I don't feel that an object that was invested with so much energy by so many people can ever totally lose all of its power. Maybe there's power residue? "

An example of a Nkisi made by Stout:

Back to The voodoo doll