In “Dionysus” I have already outlined the qualities of the god that apply to the experience of masking, except one: the effeminate, or androgynous, nature of Dionysus. The dynamics of male and female boundaries in Dionysian theater are quite fluid and are a large part of the nature of theater. Froma Zeitlin has pointed out four ways in which femininity on stage is represented and it is my belief that this is interrelated to the use of masks, and the portrayal of “the other”.

The first element of theater through which gender norms are explored is the exploration of body. Zeitlin points out that when the body “is reduced to a helpless or passive condition” (pg. 69) it is most likened to a female body. If the body is experiencing some great emotion or pain, than the character is aware of his body because the character’s body is more subject to the world around him, thus connecting him to a woman’s body because a woman is perceived as “more open to affect and entry from the outside, less easily controlled by intellectual and rational means” (pg. 65). This can be seen in both the plays of Hippolytus and Heracles, when both characters are likened to women as they are dying. This element connects to masking because as Zeitlin points out a woman’s body is viewed as “dustropus harmonia”, or an ill-tuned harmony. She says a woman’s body is “constantly at odds with itself, subject to congenital dissonance between outside and inside. Woman can never forget her body,” (pg. 70). The mask is a tangible representation of this dissonance and, therefore acts as a mediator between the conflicting outside and inside. The actor is male, but he is playing the female, thus dissonance is created and the actor is constantly at odds with himself. The actor can never forget that he is playing this character, because the mask is always on his face as a physical reminder of his “female” body. In addition, it is important to note here that a mask is a thing that has a both inside and outside and when a mask is in performance no one person can experience both sides.

The second element that also plays with this “inside/outside” theme is the concept of theatrical space. The relevance of the placement of the chorus has already been discussed in “Greek Society”, but what of the staged area where the actors perform? This staged area, by convention, is always constructed as the outside of a building so that the implication of exiting the stage is to go inside the house. Inside the house is the female’s territory, while the male is the ruler of the outside, where women have no power. This is the reason Clytemnestra had to lure Agamemnon into her realm, before she had the power to kill him. When women are outside the house, they must always provide a reason, like bearing libations in the case of Electra. Although women are forever bound to the interior of the building Zeitlin notes that “what happens inside must always in way be brought outside” (pg. 71). Masks are the medium through which the interior is brought to the exterior. For the portrayal of “the other” in Greek Theater, the portrayal of women, the interior must be brought to the exterior through the mediation of a physical boundary. The excuse for this “other” to be brought out from the interior is, of course, theater itself.

The third element is the plot of Greek Tragedies and their characteristic of anagnorisis, recognition (see The Plays). Zeitlin emphasizes the double-ness of Greek Tragic plots, something I have already discussed in “Dionysus”. Characters are often caught in double binds between “’self’ and something greater at work that is divine” (pg.75). She says that “tragedy is the art form, above all, that makes the most of what is called discrepant awareness-what one character knows or the other doesn’t or what none of the characters know but the audience does” (pg.75), which is interconnected to the belief that “deceit and intrigue” (pg. 76) are a natural part of the sphere of women’s operations. The physical element of the mask that I would like to emphasize at this point is the aforementioned “inside/outside” of the mask. The actor never gets to see himself as a mask, but the audience does. The audience gets to see a character’s true features, even though the character remains unaware of his real appearance.

Finally, the fourth element, briefly discussed elsewhere, is the element of mimesis. This element “focuses attention on the status as theater as illusion, disguise, double dealing and pretense” (pg. 79). Plato was a vehement opponent of mimesis because a person can lose themselves in the character. Plato is not a big fan of people portraying “the other” especially something as dangerous as women, who speak double. As I have already discussed, wearing of a mask is the literal doubling of one’s face. Thus, it allows the actor to speak double and in some particular cases, see double as well. Zeitlin puts forward the example of Pentheus in The Bacchae. Only after Pentheus dons women’s’ attire does he seen in double: “I seem to see two suns blazing in the heavens. And now two Thebes, two cities, and each with seven gates. And you- you are a bull who walks before me there. Horns have sprouted from your head. Have you always been a beast?” (Ln 918-22). By costuming himself he sees through both his male eyes, and female eyes, thus seeing a double world with new possibilities, much like the exploration of theater and the unlocking of new points of view through artistic expression. Like Pentheus, when you wear a mask you see not only through your eyes, but the mask’s eyes as well.

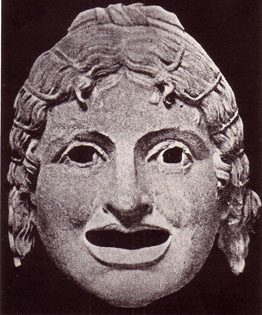

Once again the mask is an important physical arbitrator between the difficult boundary of man and woman, or man and “other”. Masks are the representation of this other, much in the way that Dionysus is the ultimate “other”. He is neither male nor female, he is not human, nor animal, nor is he really even Greek (Zeitlin calls him the “Asiatic stranger”), and most importantly: he wears a mask as the definition of his “otherness”, to mediate his relationships in the world. The actors of the Greek stage follow suit.

Back to THEATER