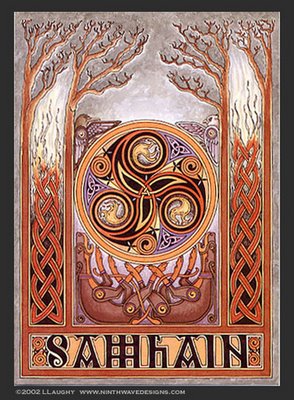

Most people agree that the origins of Halloween reside in the Celtic Festival of Samhain (pronounced Sow-an). This is the festival celebrating the time of year when “the summer goes to rest”. It was an agricultural festival and a time for “stock-taking” before the winter (Rogers 2002). Samhain was also, like we would expect in an origin of Halloween, a time of “supernatural intensity” where the force of darkness and decay were said to be abroad, spilling out from sidh, the ancient mounds or barrows of the countryside” (Rogers 2002). At this time of year the Celtic people would build a large bonfire in the hope that it would please the gods and help the regenerative agricultural process. This foundation in an agricultural based festival is still visible today where in many agricultural based communities “the intervention of masks may help ensure that the crops grow well” (Mack 1994). For the Celts this time of year held great symbolic significance, and it was said that many Mythic kings and heroes died on Samhain.

Most importantly, Samhain was viewed as a borderline, or liminal, festival as the separation between “summer and winter, lightness and darkness” (Rogers 2002). It was a time “when the normal order of the universe is suspended” (Rogers pg. 28) and ritual transition and altered states were both possible and expected. When we look at our descendant of Samhain and its history in North America we can see that the festival still carries this element of liminality. Halloween within the US used to be a time for those “between childhood and adulthood” to go perform acts of trickery. For example, when the World’s Fair of 1934 ended on Halloween “some 300,000 revelers, some masked as witches, took complete control of 32 miles of streets and concessions” (Rogers 2002). The feature of liminality actually assisted the development and appeal of the festival in North America which “stemmed precisely from the temporary freedom that it gave to young people to defy social convention” (Rogers 2002). This trend can be linked to other festivals of its kind (see Liminal European Festivals) because “below the surface of dominant European culture a current of implicit beliefs expressed in practices incompatible with the dominant of religious tenets and related ultimately to pre-Christian ideas” continues to persist (Jenkins 1994). Thus the liminality handed down through the generations from the Celts, is still present and giving a certain amount of expectation and freedom to the festivities of Halloween.

Back to HALLOWEEN