As we have seen, the interaction between the ball and the foot is a complex one, creating a whole host of long term effects such as unique muscle memory and a heightened sense of special awareness. But are these characteristics the ones that have propelled football to its premier place in the global consciousness? Is this what has given football its incredible social and cultural power? Many sports are team-oriented ball sports; more still create muscle memory and change how the player perceives and navigates space. And so, we are left to seek alternative answers.

The only thing unique about football is its use of the foot; or, more precisely, its rejection of the use of the hands. Therefore, in order to understand the world’s relationship to football, we must first look at the world’s relationship with feet as compared to hands. Only then can we fully glimpse how football came to be associated with issues of identity, class, and history.

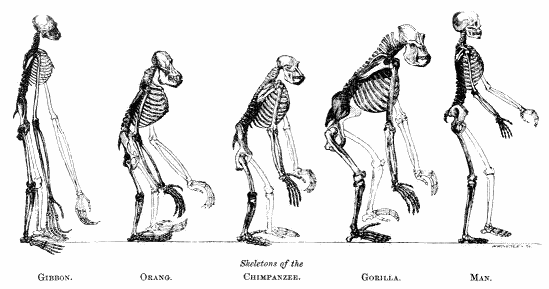

It turns out that the West’s relationship with the feet has been a troubled one. Tim Ingold, in his seminal piece Culture on the Ground: The World Perceived Through the Feet, analyzes and traces an international bias against the foot stemming from the time of Darwin. According to Ingold, since Darwin outlined his theories regarding human evolution in The Descent of Man in 1874, Western society and Western thought have operated with a profound bias against the feet. This bias stems from issues Darwin outlines regarding the division of labor between the hands and the feet. As we briefly talked about in class when we looked at the blade, human evolution is widely considered to be made possible through the use of the hands in conjunction with the use of brain, and this is only possible through bipedal locomotion. By walking on two legs, man frees up his hands, which can be used to create tools, and it is this externalization of evolution in the making of technology that has been the benchmark of human evolution. Darwin himself wrote that “man could not have attained his present dominant position in the world without the use of his hands”1, and this use of the hands is considered possible only when the task of movement is delegated to the feet. Thus, our feet become relegated to simple tools of movement like every other mammal; it is our hands that make us human.

Ingold suggests that this idea of the foot being rooted in nature, while the head and hands extend into the enlightened, civilized world, has created a profound desire for modern man to be ‘groundless’ - as far from the natural, savage world as possible.2 In doing so, he traces how civilized man has attempted to ‘leave the ground’, in terms of sitting high off the floor, building structures that rise vertically and not horizontally, and in the perception of movement itself. So severe was modern man’s conviction that intelligence triumphed over instinct, writes Ingold, that he came to consider motion at all, and therefore any use of the feet, as something belonging to only the common man. Ingold explains how traveling is rooted in the concept of a travail - - literally a labor.

Thus, issues of moving on foot, and the use of the foot at all become deeply intertwined with issues of class and identity. The biases against identifying with feet can still be found today – for instance, consider the pejorative use of the word ‘pedestrian’. Another example can be found in the German concept of fussvolk – literally a ‘foot-people’ – that is roughly equivalent to the idea of ‘plebs’. In fact, issues regarding identification with feet can be found in ancient times as well. For example, Oedipus literally means ‘swollen-foot’ in Greek – a reference to how he was crippled by the binding of his feet as an infant. Throughout the play, Oedipus is visually identified with a limp. Thus, there is a way that his deformed feet foreshadow the events of the play; his flawed human actions reflected in the flawed use of his foot -- the very thing that he needs to be human.

Because of the foot’s association with the workingman or the masses, football has an inherent commonality to it - by definition it represents the working people. Football has long been described as the game of the masses, and we would argue this is purely a result of the sport’s emphasis on feet. An activity that so heavily revolves around feet and rejects the hands also has an inherent counter-cultural feel to it; in a world so heavily dominated by this bias against the foot, an interaction which uses the foot as its primary driver is somewhat of a rebellion against the world we live in by definition. It is no coincidence that organized football as we know it first appears at the end of the 19th century - less than fifty years after Darwin's writings and the cultural bias against feet reaches its zenith. This inherent rebellious characteristic of the sport, combined with prepackaged issues of personal and cultural identity that come with any activity that uses feet, makes football uniquely situated as an outlet for issues regarding national and personal identity and counter-cultural ideals. However, football is not only a representation of these issues; as we shall see, football shapes and changes cultural issues as much as it is affected by them.

1 Darwin, Descent of Man, 76

2 Ingold, Culture on the Ground, 321

Next: Part III: 'The Ultimate Goal' - How The Football Impacts Cultural and Social Relationships

Back to The Football