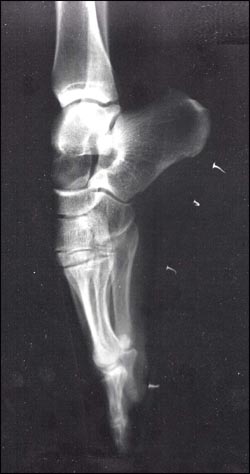

To understand the anatomy of a pointe shoe, it is first necessary to understand the anatomy of the foot. The foot is in control of the shoe, shaping it by articulating the joints throughout the foot.

The foot connects to the leg at the ankle with a saddle joint that allows for a great amount of mobility and rotation. This enables the foot to be pointed, creating a straight line through the leg and out the end of the foot. This is the desired aesthetic and creates an illusion of length. However, feet do not point from ankle mobility alone. They also depend on dexterity in the toes and flexibility in the arch. In his article, “Culture on the Ground: The World Perceived Through the Feet,” Tim Ingold (2004) states that modern humans have lost the use of dexterity in their feet, due to having them so often encased in shoes. It can be argued, however, that dancers have heightened dexterity, with their feet made all the stronger through repeated exercises performed while wearing reinforced shoes (Stern, 1980).

Pointe shoes can also be said to have an anatomy, with an internal structure that creates the outer appearance. The structure of pointe shoes comes from the hardened box of the shoe, protecting the toes and keeping the top part of the foot in proper alignment. The box as a whole is comprised of multiple parts. The vamp is the distance from the tip of the shoe to the drawstring. And the length of one’s toes determines whether a longer or shorter vamp is more suitable. The shape of the foot also determines the shape of the box; some shoes are widest at the base of the toes and then taper towards the tip, while others are a uniform width throughout. The platform is, as the name suggests, the flat tip upon which a dancer balances. Modern shoes have platforms with a surface area of several inches, but old shoes required perching on a much smaller area. Wings refer to the slightly reinforced section on either side of the box, not as hard as the vamp or the platform. They become increasingly soft towards the back of the shoe as there are fewer layers between the outermost satin and the innermost lining, because they need to allow the dancer to smoothly roll through the demi-pointe position to full pointe (Barringer & Schlesinger, 2004; Berardi, 2008).

The shank can be considered the backbone of the shoe, running the length of the sole from the ball of the foot to the heel. It is flexible so that it can bend in the shape of the foot, but it must also provide support, particularly at the curve where the arch meets the heel. These parts of the shoe are most integral to their function in allowing dancers to stand on the tips of their toes. Other parts of the shoe, such as the heel section are no different from any soft ballet slipper worn by children, or indeed any ladies flat shoe (commonly known as ballet flats for this very reason) (Barringer & Schlesinger, 2004).