Exoarchaeology

The relationship between man and space trash is evident in the archaeological nature of garbage. Before getting into this I want to mention that, for me, archaeology is the scientific study of people of the past through objects. There has been extensive debate as to what qualifies an object as being worthy of archaeological study, and as to what the past entails, like the fifty or two-thousand year rule. In this vein, Shanks writes, “…the ‘Garbage Project’ at the University of Arizona began systematically collecting, sorting through, and recording household refuse…Most archaeologists denied that the Project’s workers were doing archaeology…citing the ‘fifty-year rule’” (Shanks, 68). I think that the actual definition of archaeology is larger than any label can apply, and in this vein, I think Shanks and Rathje make a valid point that, “archaeologists study garbage” (Shanks, 65), and that, “Garbage: 99 percent or more of what most archaeologists dig up, record, and analyze in obsessive detail is what past peoples threw away as worthless…” (Shanks, 65). Moreover, I think their definition of archaeology is one of the better ones because they think that the study of the product of culture is often more valuable than studying culture itself.

Ex- or Exo- archaeology is the archaeology of outer space. This sometimes seems to focus on alien material we could potentially find as it comes through the atmosphere or is spotted on radar. For instance, the Allan Hills meteorite from Mars found in Antarctica purportedly contains biological tracings: http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/solarsystem/meteorite_chain_010226.html. In this paper, as you know by now, I decided to focus on man-made space junk, rather than meteorites or alien (make-believe?) material. Space junk is significant archaeologically as it continues to fall to Earth on one level, because it has the potential to tell us about the space race, Cold War, more recent global politics, government spending, business spending, hidden spy technologies, and therefore about our grandparents, parents, and ourselves. On another level, the existence of significant quantities of space trash and the fact that we’ve polluted beyond our atmosphere says a lot about our society in terms of a consumer- based disposable culture. Shanks writes that modernity’s ruins are located in the landfill:

“We are defining garbage broadly as subsuming themes of ruin, remains, discard, decay, hygiene, dirt, and disease. We are including cognates such as litter, trash, and junk, though we may choose to give these more specific focus…Just think of where modern ruins are. Ask what happens to buildings today. Most landfill sites are dominated by building rubble. Landfill sites are modernity’s ruins” (Shanks, 67).

Shanks and Rathje don’t take this step, but given their definition of garbage and of ruins, I think it’s safe to classify Space Junk, in addition to landfills as “modernity’s ruins.” Interestingly enough, as I continued to read the article it seemed as though everything the authors discuss also applies to Space Junk:

“Garbage and site formation processes are conceived as means to an end—metamorphic processes that come between what archaeologists deal with in the present and what they desire—past culture, social processes, whatever” (Shanks, 69).

“…both ruins and junkyards compress space and time into a single point—artifacts from different times and places are brought into one location, to be (re)discovered” (Shanks, 78). On a personal and societal level we aim “to totally eradicate our discards...no society has ever invested more thought and resources into ‘getting rid’ of its unwanted remains than contemporary America” (Shanks, 69).

To this last point, there have been numerous proposals to launch our actual garbage (particularly hazardous wastes) into outer space. I found a number of articles and heated discussion about proposals to put nuclear waste on the moon or launching it into the sun. This seems like an absolutely terrible idea at first, yet if an accident doesn’t happen during launch or the material doesn’t find its way back to Earth, this might actually be better than our current system of putting debris under Yucca Mountain right near a fault line.

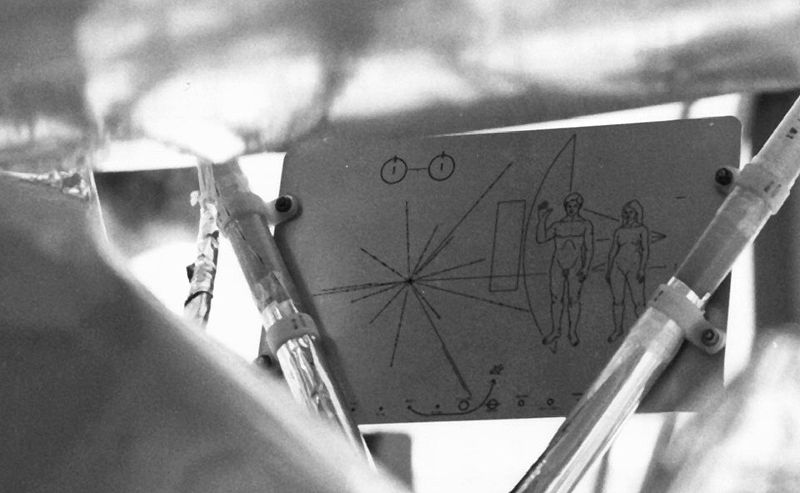

Space Junk is of definite cultural significance in terms of human-thing engineering and “reverse-engineering” in the manner discussed the Man and Satellite section. Other cultural aspects tied to space junk include recordings of human voices put on CD’s in some satellites, to the plaque discussed in class designed by Carl Sagan and put on research Satellite Pioneer 10 in 1978. There’s a lot more information available at a space archaeology wiki in the works cited section of this paper. Although archaeological study of these materials needs to be done, there’s the problem as to how to accomplish this. We can wait for things in LEO to crash down to Earth, or we can proactively decide exactly what the most significant items would be for study and then launch retrieval missions.

Carl Sagan's Plaque

The Satellite main page