The Tommy Gun is inextricably linked with media—especially film. It's easy to conjure up an image of someone holding a Tommy Gun, whether its a gangster in an adaption of the St. Valentine's Day Massacre or a soldier in World War II from a propaganda short. It's similarly easy to think of social debates regarding film in general, for how it desensitizes the viewer to violence. Although this is still a fairly active debate, an argument that film does not desensitize a viewer would be hard pressed to prove its claim using any film where the Tommy Gun is present, as we’ll soon see. We've already talked about how the Tommy Gun is practically violence incarnate; its very presence in a film nearly requires massive amounts of violence and death to be portrayed by the movie's end. However, to really explore this argument, and to see how the Tommy Gun plays a role in it, we don't need to focus on the content of the film; rather, we need to see what goes on in the collective mind of a society as they view the Tommy Gun producing violence. Thus we get to our final factor of the Tommy Gun—its social perception, or in this case, its social perception in the media. In this discussion we wonder: how does the Tommy Gun’s presence in film cause changes in our perception of violence?

Before we get to the social perception of the Tommy Gun, or even the Tommy Gun at all, let's briefly consider the social perception of the films in question in the first place. What we want to look at is the gangster in the gangster movie (Think The St. Valentine's Day Massacre, Little Caesar, The Public Enemy--you know, Gangster Films.) and how the allies' soldiers in World War II were portrayed in war propaganda. In both of these instances the people involved are glorified—the gangster is glamorized, whereas the war propaganda drums up positive support for the soldier. This was especially true in the case of the gangster, despite the apparent social negativity towards the actions of a criminal:

"It is often asserted that the bloody happenings of St. Valentine's Day, 1929, started a public revulsion against the activities of the large-scale organised criminals like Al Capone. Be that as it may, one cannot deny that, at a time when the weekly cinema audience in the United States was 60-65 million, the success of films like Little Caesar meant that a sizeable section of the public were not altogether opposed to gangsterism and its values." (Ellis 1986)

Social support for the American soldier generally makes sense. The soldier represents the ideals of patriotism and protecting one's country. However, what do we make of such strong social support for the gangster? Surely, at least in theory, the criminal is condemned by society. And yet, somehow the gangster in the twenties and thirties, at least in fiction, was in many ways idolized as well.

We can see why the gangster was idolized by looking at how he was portrayed in film. Often it’s said that “bad” people in movies are idolized because they are rebellious or some other socially looked-down-upon trait. If we look closer, however, we can see small shards of positive ideals among the debris of criminality, especially in the context of the 1920's and 1930's. For one, in the Great Depression, many Americans might have seen the gangster as someone who took matters into his own hands. If the government would not help the citizen, then the citizen would help itself. This concept also lended itself to the American ideal of individualism and self advancement, with the gangster acting as a sort of Horatio Alger figure, using his wit, perseverance, and some luck to achieve success and wealth—with this, as Ellis notes, the ideal of the American dream had somehow gone sour (Ellis 1986).

Let’s put aside these newly discovered half-ideals for a minute and look back at the basic two figures seen in film with a Tommy Gun: the soldier and the gangster. So far we've yet to include something very important: the violence itself, as portrayed in the film and produced by the Tommy Gun, which in turn is controlled by the soldier or the gangster. Usually, this is where discussion about media and desensitizing violence stops--ie., gangsters and soldiers endlessly shooting on screen desensitizes the viewer to violence.

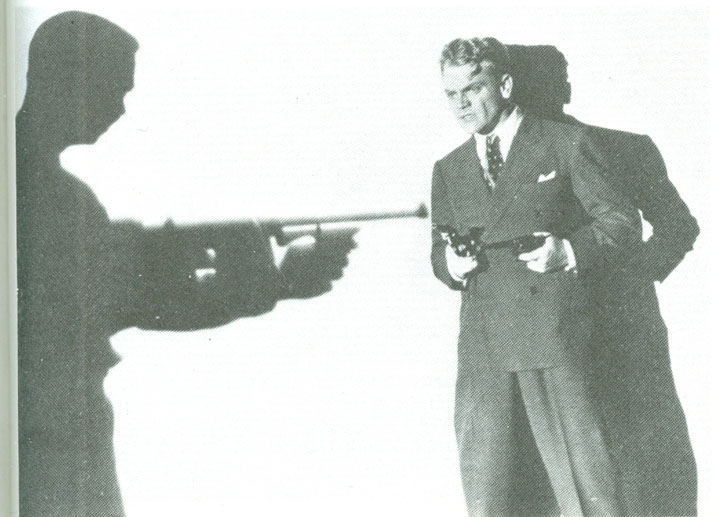

But we can yet delve deeper into this discussion when we consider what, exactly, makes up the images of the movie gangster or the soldier in propaganda. More specifically, these images aren’t just defined by the person we see—they are indefinable without also acknowledging their relationship to things. A gangster without a Tommy Gun or a solider without a submachine gun seems incomplete enough just in principle, and in film such an omission seems almost fatal: the viewer expects these things to be with these people in media. Without it there is an inevitable wrongness with the image portrayed.

By extension we can’t simplify the overall glorification of the gangster or the soldier—we have to consider the Tommy Gun and the human as conjoined but still distinct entities. Each entity represents different principles when seen in a movie. The soldier and the gangster carry the ideals they represent, however flawed or clouded they may be, which then become ingrained into the overall image that is glorified. The Tommy Gun’s presence ingrains violence in raw form into the image as well, which brings us to the crux of the glorification of violence: violence itself is not so directly glorified as much as it in a sense attaches itself to the ideals represented by the human in the relationship and subconsciously rides on the coattails of the ideals’ increasing positivism. In simpler terms, the ends (ideals) and the means (violence) of the gangster or the soldier are glorified together, resulting in the image of violence becoming not fully positive but instead simply tolerable and normal.

The situation becomes even more problematic when we put the Tommy Gun’s penchant for unqualified and continuous violence into the mix: now the violence of the gun is not even associated with possible positive ideals associated with violence in media such as courage or skill, because the nature of the Tommy Gun diminishes the need for either trait. The gun kills quickly and easily and requires little to no skill in aiming or decided when to shoot, and it is so massively powerful that as long as one shoots first the gun carries little risk of failure or one’s own death, especially considering how hard it is to miss with a Tommy Gun.

The Tommy Gun also specifically plays into this situation because of its iconic status as a producer of violence. In many ways film acts as a cycle for the Tommy Gun to become known more and more as symbolic of raw violence and death—the Tommy Gun in history is extremely violent, which is the basis for its extremely visible and iconic violent nature in film. And as the Tommy Gun attracts film makers to the 1920’s or World War II again and again it becomes more and more violent—thus desensitizing the violence it produces more and more as it is repeated through history in the form of movies. Even if another, later model of submachine gun is present the film (and think of how many submachine guns are present in modern films—very, very many) some amount of the violence portrayed is linked to the Tommy Gun simply because the Tommy Gun was the first of its kind—the first gun capable of continuous and unqualified violence. In this way the reality of the Tommy Gun seems to be forever blurred by itself and its ancestors, immortalized as the gun that grows up alongside the movie. And the desensitization and glorification of violence we have discussed continues all the same, and will likely never end considering America’s constant fascination with its violent past.

Thus we can see how the Tommy Gun in media could have changed itself. We also see how it changed us—it desensitized us and conditioned us to be able to refer to such a deadly device with ease, not because we condone violence but because we forget to take into account the nature of human-thing relationships when we develop our ideals and take in influences from the world around us. If there is a basic lesson to be gleaned from this discussion, it is that just as much as things evolve, they shape us. They always condition our minds and perception in both positive and negative ways—the Tommy Gun is no different.

From here you can go to:

Continuous Violence: Limitations, Adoption and Context

Social Acceptability: How Does Society React To Unqualified Violence?

Or if you've finished all three: