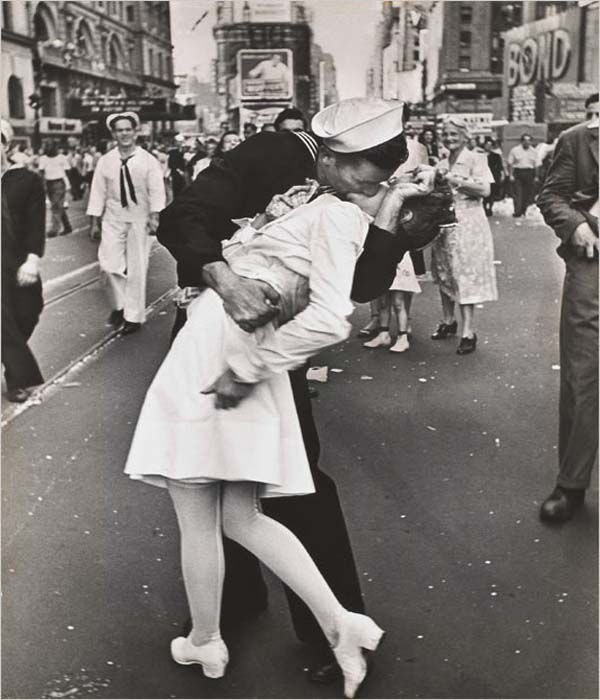

Think, for a second, and visualize what comes to mind when considering the close of the Second World War. Perhaps, for some, it is the photograph of a sailor returning home to kiss a woman out of sheer joy. Perhaps it is the patriotism-inspiring image of five marines lifting a flag atop a Japanese knoll. But for millions of Americans in the late forties and early fifties, it was something far worse. The minds of civilians were dominated by the horrific imagines of Auschwitz’s mass graves, carbon shadows of hundreds of thousands disintegrated by a single bomb, Omaha beach turned red with the blood and viscera of thousands of young American men.

These atrocities, in the minds of American civilians, destroyed the notion of the natural body. How could these four limbs constitute God’s greatest creation? How could this bag of flesh possibly hope to survive in a mechanized world of destruction? Fear gripped the hearts of millions. War could no longer be imagined as a source of honor and glory, only a terrifying machine built for terror, pain, and death. These sentiments are perhaps best captured in William Faulkner’s iconic Nobel Prize acceptance speech given in Stockholm on September 10, 1950:

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid: and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed--love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice.”

Yet in his lament for humanity, Faulkner offers a guiding light for the future. He tells us to forget our fear and to labor, to devote all the mental and physical power of the individual to elevate humanity, to rebuild.

Consider, for a moment, the state of American civilian life in 1940. The “mobilization of hundreds of thousands of women in the labor force, combined with the prolonged absence of men from traditional positions of family and community authority, began to give a new shape to civilian domestic culture.” 1 Millions had purchased best-selling book, “Generation of Vipers” in 1942 which author Philip Wylie “coined the term ‘Momism’ to describe what he perceived to be the emasculating effects of aggressive mothers and wives of the behavior of passive sons and husbands as a consequence of the reconfiguration of traditional gender rolls.” 2

At this moment in American history, fear held sway. Civilian men were terrified of losing their power to women. Women feared the potential backlash of the male dominated culture. War veterans worried away every minute of their voyage home wondering if they would have a place in their society. The recently disabled feared the ostracism of their pre-war friends. And in the back of every mind was the looming darkness of annihilation by the atomic bomb.

Now consider the following story: Jimmy Wilson, army private, sits restlessly in his transport plane. Suddenly, in a burst of flame and light, the plane is shot down, hurtling to the ground. The other nine men are killed instantly. But Wilson survives. For forty-eight hours, he lies in agony amid the smoldering wreckage until he is recovered. Army doctors, in a last ditch effort to save his life, amputate all four of his arms and legs. Less than a year later, with the aid of a wheelchair and two mechanical arms, Wilson owns his own house, where he lives with his wife, Dorothy, and is studying law under the brand new GI bill. 3

Could there possibly be any greater testimony to the power of the human to rebuild himself? If Wilson could overcome so impossible an obstacle, men could regain their masculinity, women could find their place in the workforce, veterans could become heroes in their hometowns, the disabled could achieve normality in American society, and most of all, humanity could triumph over its wartime atrocities and infernal weapons of mass destruction.

All of this hope for the future was born from the prosthetic. The image of the disabled man no longer inspired a sense of social awkwardness or weakness. The prosthetic limb was no longer an attempt at simulating a human function: it was a genuine attempt at improving the natural state of man. The holy study of medicine had become paramount in American culture. And for the first time in history, prostheses were a part of normal medicine, not some strange afterthought or a half-venture into aiding the disabled.

Certainly, something other than advances in materials such as “acrylic, polyurethane, and stainless steel” 4 allowed for this monumental shift in conception. I argue that we owe this transition to the destruction of the body. While wartime horrors were exactly that, they shattered man’s image of the body as the pinnacle of natural achievement. After the Second World War, the body was no longer seen as an untouchable paragon, but merely an opportunity for improvement.

Back to The Wheelchair Table of Contents

Footnotes

1 Serlin, David. The Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2004. p. 23

2 Ibid, p. 23

3 Ibid, p. 30

4 Ibid, p. 26