Battles depicted in art are familiar scenes throughout the history of Ancient Greece, beginning with the Mycenaean culture of the early Bronze Age. Throughout the rise of the polis, war scenes lauded the Greek culture and heightened a sense of nationalism and Greek pride. They appeared in many mediums, from the painted clay of pots to the huge stone pedimental sculptures of temples. Interestingly enough, there is only one existing temple decoration that shows a historical battle, rather than a mythological one. The Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis in Athens shows the defeat of the Persians within its pediments. But aside from the Temple of Athena Nike, pedimental sculptures largely illustrated myths and legends from Greek history. Such legends include the battle of the Gods and the Giants, the Amazons and the Greeks, and the sack of Troy. However, the most identifiable of all these battles is undoubtedly the epic battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs.

In a sculptural context, centaurs are difficult to misidentify, with their human torsos perched on top of equine withers. These mythological hybrids of man and horse represent the wilder, untamed side of human nature. They were said to be susceptible to all sorts of “animalistic” vices, and are infamous for their tales of drunken debauchery. Centaurs are a staple throughout Greek art and literature. According to legend, the race of centaurs descended from Apollo. It is said that the warriors Centaurus and Lapithes were the offspring of Apollo and the river nymph Stilbe. Lapithes went on to found the Lapith race while the deformed Centaurus mated with mares to produce centaurs. Therein lies irony of the battle between the Lapiths and the centaurs; it was, essentially, a battle of brothers.

The legend goes that the centaurs were invited to the wedding of King Pirithous of the Lapiths and Hippodameia. Apparently, the centaurs couldn’t quite hold their liquor. Everyone drank copious amounts of wine, and as Pirithous and Hippodameia were about to be wed, the centaur Eurytion jumped up and attempted to make off with the bride. This caused quite a stir as each centaur took it in his head to violate the wedding guests. Of course, the Lapiths would have none of it, and a great battle ensued. The Lapiths emerged victorious, and drove the centaurs from their lands.

The Temple of Apollo at Bassai

Above is a photograph of the frieze from the Temple of Apollo at Bassai. Currently, this frieze resides in the British Museum in London. However, it once graced the walls of the Temple of Apollo, bordering on a gaudy glory. According tho Biers, the highly ornate sculpture is gracelessly executed, only a pale imitation of the Parthenon.

At Bassai, the Amazons battled here near the centaurs in stone, as the valiant Greeks fought each vicious opponent off. The sculpture here is unusual for the extreme nature of the relief; in some places, the figures have broken almost completely free of their stone background. Each clump of fighters is separated from the rest, so that the battle is easily untangled by the eye.

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia

The drawing pictured above is a reconstruction of the western pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, built in the fifth century BCE. Here, the centaurs appear in rare form, grimacing at their foes and captives. One centaur growls as his intended victim elbows him in the temple; yet for all of the horror of her situation, the woman's face remains expressionless. This pediment summarizes wonderfully the severe style of the first half of the fifth century BCE. Apollo presides over the slightly wild scene, while each perfect human being seems to gaze vacantly at the viewer. Incidentally, centaurs make excellent subjects for pedimental sculptures because of their unusual shape; their rectangular form is well suited compositionally to a triangular pediment. The remains of this pediment can be seen today in the Archaeological Museum in Olympia.

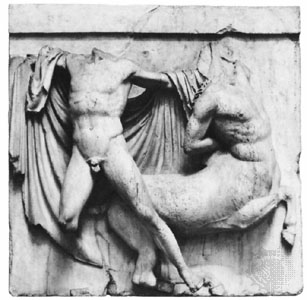

The Parthenon

The ever present centaurs appear again on the metopes of the parthenon (see above). Here, the centaurs must share architectural prominence with the Amazons, the Giants, and the Trojans as enemies of the Greek state. As the metopes were carved by various sculptors, they vary greatly in aesthetic value. The metope pictured above is considered of one the most technically skilled and compositionally sound of all of the depictions of the Lapiths and the centaurs in the Parthenon. The folds of the fabric serve to bring the figures of man and centaur forward in space, while the fabric itself has been carved in a very technically skilled manner. Man and beast strike a beautiful balance here, as the outstretched arm of the Lapith counters the heavy forelegs and shoulders of the horse.

The Temple of Hephaestus

The Temple of Hephaestus is particularly interesting because it represents a transition in classical architecture. It was build in the fifth century, and while the outside seems absolutely Doric in style, the inside contains the first Corinthian column, and many Ionic characteristics. The centaurs pictured above appear in an ionic frieze stretching the circumference of the opisthodomos.

-

Shanks, Michael. Classical Archaeology of Greece: Experiences of the Discipline. United States: Routledge, 2004.

Whitley, James. The Archeology of Ancient Greece. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

-

Posted at Dec 11/2007 10:14PM:

keffie: I really like your treatment of this common theme in different media and contexts. Good connections.