Amarna: The City of Akhenaten?

|  |

Whit Schroder Amarna Final.doc

Whit Schroder Amarna Final.doc

In the middle of the 14th Century BC, the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten adopted the main worship of a single god, the sun-disk or Aten, eradicating Egyptian traditions that had lasted for millennia and drastically altering the art style to reflect this new freedom of expression. Along with these changes, Akhenaten moved the Ancient Egyptian capital from Thebes to a new city, ancient Akhetaten or modern-day Amarna. Most current research has relied on texts that reflect the views of the pharaoh and the elite. Admittedly, little other evidence from material remains has been available. Texts describe Akhenaten's founding of his city based on his personal vision of the Aten. In my paper, I will attempt to find evidence suggesting a larger role of private citizens in the construction of the city, whether eugertism played an important part in its brief success. Was Akhenaten a tyrant who forced his own idea of the Aten and Egyptian religion on his subjects, or were citizens allowed to practice their own beliefs? Did Akhenaten have to essentially bribe his citizens, convincing them to remain in his capital or does evidence support the contrary, that loyal citizens helped to support the city through gift-giving and the funding of construction projects? If the latter, why was Amarna abandoned after the death of Akhenaten? Because the city was abandoned so quickly, archaeological evidence provides a snapshot of history that does not exist in any other city in Ancient Egypt. If this paper fails to answer the questions it poses, it will at least suggest areas of the city to excavate further, in search of answers.

Egypt Before Akhenaten

|  |

|  |

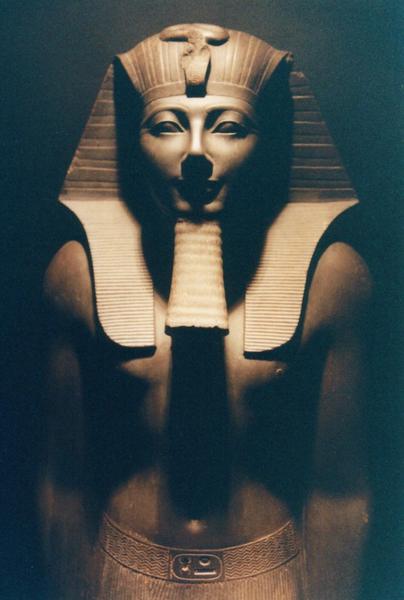

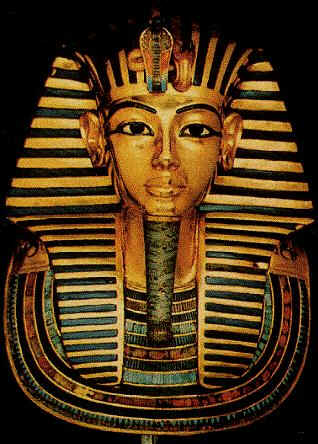

Akhenaten ruled during one of Egypt's strongest and richest periods, the 18th Dynasty, which lasted from 1550 to 1292 BC. This dynasty included some of the civilization's most well-known pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and of course, Tutankhamen. The 18th Dynasty began with the expulsion of the Hyksos, or foreign rulers, who had taken over Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, a dark ages of sorts between the Middle and New Kingdoms. The early rulers of the 18th Dynasty led numerous campaigns against the Hittites and Assyrians to the North and the Nubians to the South. The rule of Amenhotep III (Akhenaten's father and immediate predecessor) was characterized by peace and wealth, gained through the tribute from the various conquered enemies.

Akhenaten was born Amenhotep IV, and was the younger son of the pharaoh. If his older brother, a Theban prince named Thutmose, had not died, the Amarna period would have likely never occurred. Amenhotep IV may have served as coregent to his father due to major illness that struck Amenhotep III in the last years of his life, though this theory is highly debated among modern Egyptologists. Amenhotep IV did not reveal his true deviations from Egyptian society until the death of his father.

The Heretic Pharaoh

Amenhotep IV's first breach of Egyptian etiquette seems to have occurred in his third regnal year when he chose to celebrate the traditional Egyptian Sed festival, normally held after a pharaoh's first 30 years of rule. Amenhotep IV then began the construction of some of Egypt's most major temples up until that time at Karnak. Not surprising was the size of these temples but the fact that they were all dedicated to one god, Aten, represented by the solar disk. At the time, some of the major Egyptian gods were Amen (after whom Amenhotep IV had been named), Ra, and Horus. Initially, Amenhotep IV shrewdly presented Aten as a combination of these three deities (Amen and Ra had already been merged into a sun cult, Amen-Ra). But soon, Amenhotep IV showed that he would not tolerate representations of Egypt's more traditional deities, and he had his scribes erase all mentions of gods other than Aten, especially focusing his crusade on the cult of Amen-Ra.

The Amarna Art Style

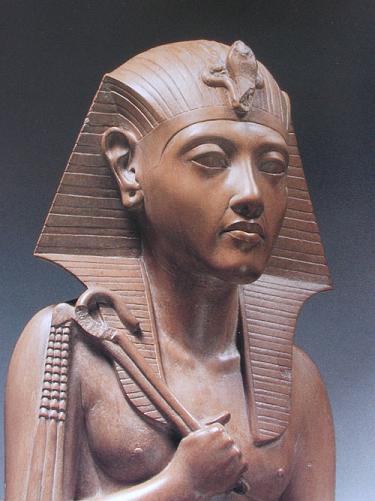

To underscore the new religion, Amenhotep IV introduced a new art style based on more fluid forms. The androgynous depiction of Amenhotep IV has inspired numerous theories regarding genetic diseases in the royal family, explained by incest, which was common in Ancient Egypt. Egyptologists have interpreted this art style as being more realistic than the traditional art preceding Amenhotep IV's reign. But a casual look at all art during this period reveals that everyone, not just the pharaoh and his family, was represented in the same manner. Other theories suggest that the Amarna Art Style was an attempt at a more fluid sculptural form or an intended representation of the pharaoh as a fertility symbol, having both male and female characteristics. Also, the royal family was depicted in more intimate scenes of worship. Soon, however, Amenhotep IV would take far larger steps in changing Ancient Egyptian infrastructure.

The City of Akhetaten

Some time between Amenhotep IV's fourth and fifth regnal years, following the obliteration of representations of Amen-Ra, he changed his name from Amenhotep ("Amen is satisfied") to Akhenaten ("Servant of the Aten"). At the same time, Akhenaten decided that in order to give Aten full attention, a new city would have to be constructed. As the story goes, Akhenaten was journeying north of the Egyptian capital, Thebes, until he saw the sun rise through a dip between two mountains, which was coincidentally the Egyptian hieroglyph for "horizon." At this spot, Akhenaten decided to build his new capital, aptly named Akhetaten, meaning "The Horizon of the Aten." The city today lies near a modern village, Et Til el Amarna, and, thus, the ancient city is more commonly known as Amarna, and the period during Akhenaten's reign as the Amarna Period. "The settlement was founded by Akhenaten in the fourth or fifth year of his reign, and was clearly intended to be a new capital city, dedicated to the Aten and therefore purposely established on a virgin site so that the new temples could be built on ground untarnished by any previous religious structures." (Shaw 1996: 92)

Amarna's Architecture

Amarna's architecture is as different from traditional Egyptian architecture as the period's art style is from art before Akhenaten's rule. Ian Shaw observes that "the presence of ramps and steps flanked by balustrades in most of the major buildings at el-Amarna suggests that Akhenaten was obliged to devise innovative architectural forms to provide suitable contexts for the worship of Aten" (Shaw 1994: 109) as Diane Favro and Fikret Yegul wrote of the utilitarian street designs in Rome and Ephesus, respectively. In Akhenaten's interpretation of religion, the citizens' honoring of the Aten involved the worship of the royal family worshiping the sun disk, as the only true connection between the Egyptians and the Aten was through Akhenaten. Thus, temples at Amarna had to have much more open space than did more traditional Egyptian temples at Karnak, and Akhenaten's adoration of the Aten had to be not only visible in art but also in person.

Other depictions of the pharaoh show Akhenaten and his family handing out gifts, in the forms of gold and jewelry, to his subjects from such ramps and steps. Was Akhenaten bribing citizens to remain in the city and follow his radical religion? Or was he simply rewarding and thanking his loyal subjects? Obviously, textual evidence would support the latter, but what does material culture reveal?

Textual Evidence Vs. Information Gained in the Field

Ian Shaw writes:

- "Throughout the pharaonic period the particular kinds of evidence provided by archaeology and texts are often difficult to reconcile satisfactorily. This is particularly true of the Amarna period, when the distinctive texts written in the temples, palaces and tombs of the elite seem to find few recognisable counterparts in the material culture of the great mass of the population. What evidence there is suggests that the 'heresies' of the Amarna period may have had surprisingly little impact on the majority of Akhenaten's subjects. The elite, however, must have felt the full brunt of the reforms, as they would have been obliged to change their names, their religious observances and even their homes (in the case of those officials who moved to el-Amarna)" (Shaw 1996: 89-90)

However, in the case of the question posed above, material remains tend to support the textual evidence. Private houses at Amarna, while having the conforming representation of the royal family and the Aten, contained depictions of other gods that were worshiped before their eradication by Akhenaten. Particularly in the worker's village, located just outside the city of Amarna, evidence shows that the workmen had private shrines to numerous gods, supporting Shaw's theory that Akhenaten's "heresies" had little impact on the common people.

Of course, all texts, describe Akhenaten's supreme role in the founding of Amarna. But did he play as large a role as previously believed. According to Alexander H. Joffe, construction of Amarna began while Akhenaten was still coregent with his father, Amenhotep III, likely during the first two years of his reign. Before Akhenaten moved the capital to Amarna, the site probably already had agricultural villages and craftsmen, "was thus partially complete when Amenophis [Amenhotep] IV assumed the throne" (Joffe 1998: 553). Amenhotep IV chose the site to be the capital because it afforded unlimited space, but was a small settlement already present before the move took place? Only further excavation can answer this question. What is known is that Akhenaten defined the site with boundary stelae, proclaiming the founding of the city.

I'm Not Done Yet!

Over the next few days, I will find more evidence for eugertism at Amarna, and I will post it here as I write my paper.

Notes

"The city of el-Amarna is unique not merely because of its unusual religious and political context, but also because of its astonishingly brief period of occupation: no more than 20-30 years. The preservation of such a wide range of architectural and artefactual data represents an unrivalled opportunity to examine the socio-economic patterns within a community which lasted for barely a generation." (Shaw 1996: 93)

"The ruler also became dependent on his newly situated bureaucrats and military ... Royal vulnerability was increased from all sides by disembedded capitals. ... Though they were part of developed state systems with complex economic interlinkages, the disembedded capitals examples discussed all appear to have had adequate local resources and rural hinterlands to be agriculturally self-sufficient ... New capitals were also centers for craft production, since elites sought to bring under control the production of the ideologically and symbolically charged architecture, art, and small objects ... The creation of palatial complexes, another common feature, provided powerful visible symbols of the new elites." (Joffe 1998: 569)

"Our understanding of Egypt is limited by a dearth of documentation from non-royal sources and by the lack of opposing voices in available sources. It appears, however, that Akhenaten adopted a radically different strategy than his Mesopotamian counterparts by depriving the religious elites of their established theological and economic prerogatives." (Joffe 1998: 570-571)

"Akhenaten began to overturn ancient economic, as well as social, expectations, apparently without attempting to mollify or negotiate with the temples ... The social distance of disembedded capitals and royal policies generated by ideological constructs had to be adequate for a regime to distinguish itself from tradition and competitors but not so great that established interests were completely alienated." (Joffe 1998: 571)

"Their instability and degrees of spatial and social artificiality are reflected in their ultimate fate, which minimally and almost invariably included the loss of status as capital and, at the extreme, complete abandonment ... The process of building a new capital is not, strictly speaking, one of disembedding but rather of reembedding to create a new locus for power which is apart from existing loci but comprised of the same fundamental components and relationships ... disembedded capitals are automatically reembedding into those patterns, entailing adroit administrative and ideological manipulations, plus a threat or the use of some force." (Joffe 1998: 573)

Selected Bibliography:

"Disembedded Capitals in Western Asian Perspective" by Alexander Joffe

"Royal Cities of the Biblical World" by Joan Westenholz

"Building a Sacred Capital" by Ian Shaw in "Capital Cities"

Shaw, Ian. "Balustrades, Stairs, and Altars in the Cult of the Aten at el-Amarna." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 80. 1994. [link]

"Social History of Ancient Egypt" Bruce Trigger

Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology of Near East

Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt