Back to The Game of Chess...

This essay will focus exclusively on chess, chesspieces, and people. However abstract as it is, it will reflect on what precisely happens while a human player goes about playing chess.

The Power of the Pawn

While the modern game has run away with embellishments to the "back row" characters, the original chatrang featured the pawn. The game's rules were simple enough that the pawn was almost a principal piece. Pawns could cluster and trap other pieces more effectively in their large numbers.

In chess, each piece carries some weight. The French ambassador Foix noted that "If we lose a Pawn it seems a small matter; but the loss often brings with it that of the whole game." (1) The possibilities in chess are such that a single pawn can determine an entirely different flow in the course of the game. Although we have previously seen an overriding medieval hierarchy, consider that a pawn may save a king or take a knight or rook. So even a smart pawn can lead to victory!

The Vulnerability of the Pawn

The other side of the story is that a pawn is a bargaining chip. The player throws his pawns at the enemy to take more significant pieces. The king is not so powerful without his lowly pawns, but this possibility is always there.

As a result, the pawn is almost always an undistinguished piece. Which is a shame, in light of the above. Crucially, however, the pawn is a mere tool in the course of winning the game. Henceforth and forever, the pawn is a figure without agency. Extended further, the pawn is at the will of authority.

We're all Pawns

Except for the king, of course. Playing chess, you transcend your existence as a pawn and momentarily get to be king.

Consequences: Status

John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding cites a common theme that although the figures live out their duties on the chessboard, most of the time they are thrown into a bag and stored together. Tragically, this became a metaphor for the human condition.

In a sense, we are each drawn from the bag to play out our certain role and follow the rules that have been deigned to us by the world. At the end of the game, everybody - from king to pawn - is thrown into the same receptacle (which to many serves as the afterlife). This of course has certain implications: 1) that life and fate are random, 2) that we are bound to serve our duty, and 3) that we are all equal in death. The last point was extended to imply that one not seek to change his or her status during his or her lifetime, thus serving the narrative nobles created for feudal society. And although chess later became a democratizing factor (as will follow), even up to Locke's Enlightenment this view was meant to silence the masses.

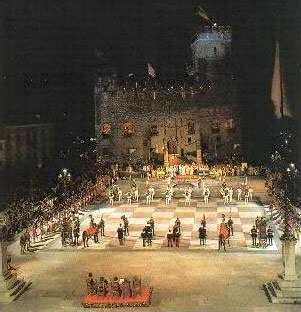

If you've ever seen a human chess match, you can see the metaphor lives on. We are all players on the stage, or equally, on the chessboard. Remaining today is the human feeling that some greater influence and or rule-set is in charge.(2)

Consequences: Occupation

Chess is constant with regards to occupation. It solidifies certain roles in the codification of its pieces - the royalty, bishop, knight, rook, and pawn. In effect, the game might be hard to coalesce with a contemporary narrative on occupation. Regardless, the game reflects a constant construction of borrowed monarchical traits from the Indian caste system, to the Persian kings, to the medieval.

With these categories, it may be seen that indirectly every person is under the influence of some king and/or queen. The wide category of the pawn seems to swallow the recently developed positions of scientist or philosopher - effectively homogenizing classes of no external authority. Those powers that are emphasized are the king and queen (dictatorial and social authority), the bishop (religious), and war-making (rook = chariot, knight). Chess would imply that all other pursuits serve the aims of these greater authorities in reality. They are not the sources of agency in chess.

Consequences: Gender

The queen did not gain her advanced movements until the 15th century. During the Persian/Indian play of the game, the piece in the queen's place was an underpowered minister to the king. While the exact reason for the change is unknown, it probably has to do in part with 1) the increased play of female scholars in the game and 2) the adoption of chess as a pastime for courtly love.

During medieval times, the role of the female was increasing, as disputes between kingdoms often rested on familial ties. In the Renaissance, we also witnessed women becoming monarchs in their own right. Thus, the game became a sort of narrative on sexual equality. Thomas Middleton's, A Game at Chess, describes a royal wedding fracas in terms of chess - and indeed, even domestic disputes could be modeled through chess. Perhaps, it is suggested, the strength of the queen piece was used as a ploy to bring Renaissance women to the table. Rather than play to win, courtiers would attempt to complement women on their chess games. It is no doubt why, during this time period, that there emerged books that described how to make moves based on a dice roll instead of by cunning intelligence.(3)

- Shenk, David. The immortal game. Loc. 1025.

- Shenk, David. The immortal game. Loc. 1075.

- Shenk, David. The immortal game. Loc. 930, 1040