| |

SUGAR, TECHNOLOGY, AND SLAVERY: THE PLANTATION

Sugar production was an agro-industrial process; it began with sugarcane cultivation, followed by a multi-step extraction that usually ended with the production of semi-refined sugar. This muscovado sugar was then shipped to Europe for further refining. Rum and molasses were also made, but rarely pictured in production. Images that focus on the agricultural part of the process tend to rework the European genre of the georgic landscape, which pictures rural life as happy, bounteous, and harmonious. The extraction/refinement process often centers on the mill and uses another European genre, the composite view, which condenses into one composition stages of a process that usually take place at different times and in different spaces.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Figuring Slavery

"Nigritae exhaustis venis metallicis consiciendo saccharo operam dare debent," hand-colored engraving. In Theodor de Bry, [America. Pt. 5. Latin]. Frankfurt am Main, 1595.

One of the first engravings of sugarcane milling and of slavery in America, this plate was made for de Bry's beautifully illustrated compilation of writings on the Americas; it illustrates Benzoni's history of the Spanish colonies. The text refers to the Spanish switching of black slaves to sugar production in Hispañola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) when gold mining ran out. Although the text identifies the figures as blacks, they are pictured as light-skinned. At this moment human difference was marked as much by culture (dress, religion, etc.) as by skin color, hair texture, and physiognomy. These figures' near nudity codes them as more savage than Europeans, thus candidates for enslavement. While processing cut cane occupies most of the composition, the viewer's attention is also drawn to distant cane fields by the smiling sun beaming down on the fields and laboring slaves.

|

|

|

The Plantation as Curiosity

"Sucrerie," engraving. In Jean Baptiste du Tertre, Histoire général des Antilles habitées par les François. Paris, 1667-71.

In this composite view of a sugar plantation in the French Antilles a white overseer, stick in hand, directs the actions of black slaves who scurry to take their bundles of cane off to the three-roller cattle mill in the background. As is common in this kind of view, cane fields are relegated to the background and shown here as a tightly compressed block. Less common is the focus on slave huts (marked 10 in the right foreground); usually they are placed in the distance when shown at all. The plate is also striking in its emphasis on tropical plants. Boldly modeled and outlined and placed like a screen in the foreground, the exotic trees and plants threaten to draw the viewer's attention away from the titular subject of the print. Natural history and production scene combine here to form a decidedly curious image.

|

|

|

Up-scale and 'Natural:' Sugar in Brazil

"Brasilise suyker werken," engraving. In Simon de Vries, Curieuse aenmerckingen der bysonderste Oost en West-Indische verwonderens-waerdige dingen. Utrecht, 1682.

The boiling house is foregrounded here; behind the slaves skimming and pouring sugar liquor are rows of cones. These are visual reminders that the Portuguese in Brazil commonly produced pure white crystals, rather than the crude muscovado that was imported to Britain, France, and Holland. Not one, but two large mills dominate the middle ground, one driven by cattle, the other water. They suggest the large scale of the operation in Brazil, where milling was often centralized and the labor force increased by planters renting slaves from other proprietors. This composite view has some of the liveliness and naturalism of contemporary Dutch landscape painting. Note here the light raking across the scene from left to right, the agitation of the water, and the hint of a breeze rippling though the sugarcane plants in the center. |

|

|

Doing Double Duty

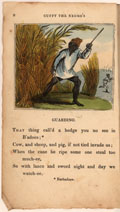

"Guarding," hand-colored wood engraving. In Cuffy the Negro's doggrel description of the progress of sugar. London, [1823].

The scores of composite views of sugar plantations published in the early modern period repeatedly draw on a limited set of scenes and visual elements that define important stages in transforming cane into crystals. Guarding introduces another element, highlighting the value of the sugarcane crop and the violence needed to protect it from animals and people. Sword in one hand and lance in the other, this slave seems ready to kill and harvest all at once. |

|

|

The French Country House Goes to Cayenne

Nicholas Chalmandrier, "Vue de l'habitation du Sr. de Préfontaine située à Cayenne/Plan général d'une habitation," etching. In Chevalier de Préfontaine, Maison rustique, a l'usage des habitans de la partie de la France équinoxiale, connue sous le nom de Cayenne. Paris, 1763.

This plate appears in a manual designed for new planters in the French colony of Cayenne. It contains two plans that offer idyllic visions of sugar plantations styled after a French country estate. On the left, the elaborate birds-eye plan includes a chapel and an olive grove, as well as a sugar mill and a cattle pen. The stress is on opulence and order: most of the estate is bounded by fences and organized by trees and paths set in straight lines. Like a French chateau, there is a formal garden, replete with ornamental fountain, next to the planter's house. The second plan (small, but still including a large formal garden) emphasizes surveillance: everything is organized along a narrow axis and the text states that all activities take place under the master's eye. |

|

|

Guarded Bounty

Brooks, "Here you may view the vast luxuriant plains, the bounteous mother of the teeming canes," frontispiece, engraving. In Joshua Peterkin, A treatise on planting. St. Christopher, 1790.

This frontispiece to a planter's manual celebrates the bounty of the sugar plantation in an amateurish image and georgic verse. Both word and image operate through excess. The verse is loaded with adjectives; in the image, leafy branches spill over the wall, and cane fields extend to the mountains. The estate's buildings are nearly obscured by the line of palm trees marching across the background. In the foreground two white men are inspecting cane plants, while a black slave cuts cane behind them. As in the previous two plates (to the left), guarding and surveillance assume visible form—here in the well-built wall with its guardhouse and large, pointed gates, which not-so-subtly frame the slave.

It is unusual to find a print engraved and published in the West Indies at such an early date, since presses for making copperplate engravings and, later, lithographs weren't imported until the nineteenth century. |

|

|

Imperial Georgic

"The Buildings of Maran Estate in the island of Grenada. The Property of Thomas Duncan Esqr.," watercolor, 1822.

This anonymous watercolor submits the agro-business of sugar-making to the conventions and ideology of georgic landscape painting. The georgic celebrates the bounty, peace, and harmony (social and visual) emanating from the agricultural landscape. This composition is harmoniously ordered through the rhythmic line of the green hills and the central trees that soften and partially obscure the buildings on the estate. Labor is banished almost completely—there are two slaves in the middle ground, but it is unclear what they are doing. The horses and cattle all seem to be at rest, although someone is working—given the blue smoke that pours from the chimney on the boiling house. |

|

| |

Exhibition may be seen in Reading Room from SEPTEMBER 2013 through december 2013.

K. Dian Kriz (Professor Emerita of History of Art and Architecture, Brown University), guest curator, with assistance from Susan Danforth (Curator of Maps and Prints); Elena Daniele (JCB Stuart Fellow 2012-13), curatorial assistant. |

|