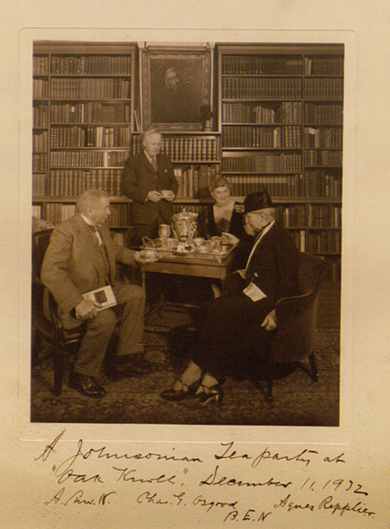

"A Johnsonian Teaparty," 1932, Photograph

(Image Source 5)

"A Johnsonian Teaparty," 1932, Photograph

(Image Source 5)

Our attitudes toward dictionaries differ vastly from those held in Johnson’s day. We regard dictionaries as reference items; it is highly uncommon to hear of a person who has undertaken to read one in its entirety. The widespread use of the online dictionary has almost entirely erased its standing as a literary artifact. But even into the nineteenth century, reading the dictionary (or portions of it) sequentially was not an unusual pastime. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in his Biographia Literaria, wrote of Johnson’s Dictionary, “I should suspect the man of a morose disposition who should speak of it without respect and gratitude as a most instructive and entertaining book …but I confess, that I should be surprised at hearing from a philosophic and thorough scholar any but very qualified praises of it, as a dictionary.” (DeMaria, 1986, p. 3). Johnson probably wouldn’t have protested Coleridge’s appraisal. In fact, he often spoke of his Dictionary (and none of his other texts) as “my Book.” (De Maria, 1986, p. 4).

A departure from the highly specialized, technical lexical indices available by the middle of the eighteenth century (over 20 such references had been produced in the preceding 150 years), Johnson’s Dictionary has a democratizing imperative. He expressed a desire to write a text to be of “advantage to the common workman…designed not merely for criticks, but for popular use.” (DeMaria, 1986, p. 12). And indeed there was great demand among the general public. At the time, the print industry was undergoing a revolution of sorts, which empowered enthusiastic multitudes to take up writing. Censorship was scaled back, the copyright was introduced and handbills, receipts, tickets, advertisements and posters began to be printed. Johnson sardonically grumbled that “so widely is spread the itch of literary praise, that almost every man is an author, either in act or in purpose.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 32)

18th Century Printing Shop

18th Century Printing Shop

Broader cultural motives were also at work when Johnson set about writing his Dictionary. Hitchings describes the dictionary’s place among a whole host of phenomena introduced to satisfy “a rage for order,” including “the price tag, standardized weights and measures, the proliferation of signposts on public highways, the increased use of account books and calendars.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 50). Moreover, as England was assuming its identity as an Empire, establishing an official, standardized lexicon was paramount in lending credibility to the new idea of “Britishness.” Hitchings maintains that “Imperialism is in part a feat of rhetoric,” requiring “Britishness, in its many guises, to be codified , in order to be exportable.”(Hitchings, 2005, p. 51). England was under keen pressure to match the accomplishments of French and Italian lexicographers.

Navigate: Don't Judge A Book By Its Cover: An Introduction / The Early Life of Samuel Johnson / The Dictionary in a Sociocultural Context / Nine Years in the Making / The Dictionary Hits the Shelves: Critical and Public Reception / Traces of the Author and his Time / Conclusion: The Legacy of a Book / *Bibliography*