"I believe I shan't undertake it," (Reddick,1990, p. 17) Johnson told his friend Robert Dodsley at the suggestion that he author a dictionary. Fortunately. Dodsley, an astute entrepreneur, was able to convince Johnson of the propitious opportunity. In 1746, the small group of London booksellers who comprised Dodsley's associates in the venture invited Johnson to draft a comprehensive description of his proposed work. If approved, they would sign a contract with Johnson to publish the dictionary.

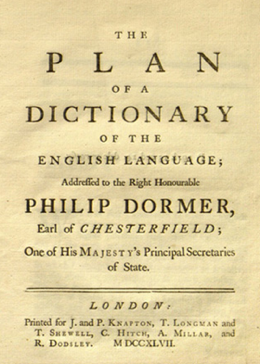

The Plan of a Dictionary of the English Language was completed in 1947. Lexicographers past had left Johnson with no records of their process to aid his work; he was left to intuit the proper methods. His detailed and logical scheme impressed the booksellers and, to Johnson’s chagrin, attracted the patronage of Philip Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield. The Earl’s backing would, Johnson reluctantly recognized, lend the project authority; the Italian and French dictionaries had enjoyed the benefaction of entire national academies. (Reddick, 1990)

Soon after signing the contract with the booksellers (which allotted Johnson £1,575 in compensation), he moved to 17 Gough Square in order to be close to his printer, William Strahan. Strahan became a close friend of Johnson’s, as well as an indispensible aid. Strahan “was his paymaster, acted as his unofficial banker, franked his letters, and even periodically provided him with breakfast.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 60). This warm account notwithstanding, Strahan was frequently the mediator between Johnson and the shareholders, who often bickered over matters of scheduling. The dictionary could not be printed all at once; it had to be set to type in installments, inspiring frequent discord between Johnson and his business-minded investors.

"No. 17 Gough Square," Artist Unknown, Watercolor

"No. 17 Gough Square," Artist Unknown, Watercolor

Johnson employed six amanuenses to help distribute the overwhelming burden of menial, mechanical labor that attended the Dictionary’s slow construction. These six men (of which no more than four was at work at any one time) were grateful to act as servants and companions to Johnson, and therein take steps to alleviate the poverty to which they were all accustomed. (Hitchings, 2005).

Despite the dedicated support of his cadre of assistants, the intricate decisions regarding content and structure fell solely to Johnson’s discretion. Johnson maintained the confident (and unrealistic) notion that it should take no more than three years. When his friend William Adams reminded Johnson that it had taken the French Academy’s forty workers upwards of forty years to complete, Johnson replied acerbically, “Sir, thus it is. This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 73). His three-year estimate was, of course, inaccurate.

In fact, Johnson composed and subsequently abandoned an entire manuscript of three years’ work, resolving to broaden his sources and methods. “The wealth of possible usages for words,” Reddick explains, “as he read through printed books gathering his examples, swelled to exceed the expectations of even the keen, extremely well-read Johnson.” (Reddick, 1990, p. 26). Writing his Dictionary was not a fluid process and he encountered no shortage of setbacks before refining his strategy. These turbulent first years also saw the death of Johnson’s wife in 1752.

The approach he eventually adopted was unorthodox. Rather than begin with a wordlist, and from there seek illustrative quotations, Johnson started with books. Most of his 160,000 quotations tap a predictable pool of English authors: Shakespeare, Dryden, Swift, Pope, Addison, Hooker, Bacon. (DeMaria, 1986, p. 17). He literally tore through stacks of material, returning the volumes he borrowed from generous collectors in varying degrees of ruin. When he found a passage that warranted inclusion in his Dictionary, he underlined the word he wished to illustrate, bracketed the relevant passage and wrote the first letter of the word in the margin. The amanuenses then copied the marked portions of text onto slips that were stored in bins in alphabetical order. This haphazard procedure caused some slips to be lost; these errors are occasionally evident in his Dictionary, as when he explains vaguely that the verb “to cream” is “used somewhere by Swift.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 79). In spite of these problems, Johnson’s system imbued his work with unique character. “His decision to extract the word-list from books,” Hitchings observes, “and his generous deployment of illustrative material, meant that his conception of the Dictionary was rooted in the experience of reading and interpreting texts. In particular, it was the naturally critical tendency of his reading that shaped the work.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 82)

A page from Johnson's annotated copy of Isaac Watts's Logick

A page from Johnson's annotated copy of Isaac Watts's Logick

Johnson’s etymologies are drawn from a more limited pool of sources than his quotations and many of the philological texts he consulted were obviously unsatisfactory in his view. Stephen Skinner's etymological dictionary was among his most frequently used sources, though Johnson seems to doubt his authority on a number of occasions. Skinner provides several hundred words on the etymologies of “brawn” and “admiral”; Johnson writes dismissively in his Dictionary that they are “of uncertain etymology.” (Hawkings, 2005, p. 97). Overall, the etymologies in Johnson’s work are concise and don’t seem to have been treated with the same exacting attention he brought to his definitions. He didn’t dare truncate definitions of even the most common words. “In” garners sixteen definitions, “up” receives twenty and “time” carries fourteen. His definition of the verb “to put” covers three pages and comprises more than 5,500 words. “To take” runs five pages and 8,000 words. Johnson presents the reader with a subtle sarcasm when, having listed sixty-four sense of the verb “to fall,” the final, sixty-fifth entry admits plainly, “This is one of those general words of which it is very difficult to ascertain or detail the full signification.” (Hawkings, 2005, p. 93). It was his goal from the start to “to pierce deep into every science, to enquire after the nature of every substance of which I inserted the name, to limit every idea by a definition strictly logical.”He would later admit that these were the optimistic “dreams of a poet doomed at last to wake a lexicographer.” (Hitchings, 2005, p. 101).

Navigate: Don't Judge A Book By Its Cover: An Introduction / The Early Life of Samuel Johnson / The Dictionary in a Sociocultural Context / Nine Years in the Making / The Dictionary Hits the Shelves: Critical and Public Reception / Traces of the Author and his Time / Conclusion: The Legacy of a Book / Bibliography