Perhaps the oldest form of clock is the sundial. This can be as simple as a vertical stick with surrounding markings, since it works by having the sun cast a shadow. As the sun moves in its daily arc from east to west, the shadow cast by the stick (also called a gnomon, hence the study of sundials as gnomonics) (Rohr 4) will change length and move during the course of the day. Sundials can be simple, but they can also be quite complex; in either case, designing an accurate one takes a reasonable understanding of geometry and trigonometry, since shadows are all about angles.

Sundials were more or less perfected by the end of the Crusades in the 13th to 14th centuries (Rohr 16). That's not to say, however, that all sundials since then are the same. They continued to vary greatly in style, form, and location. pictures

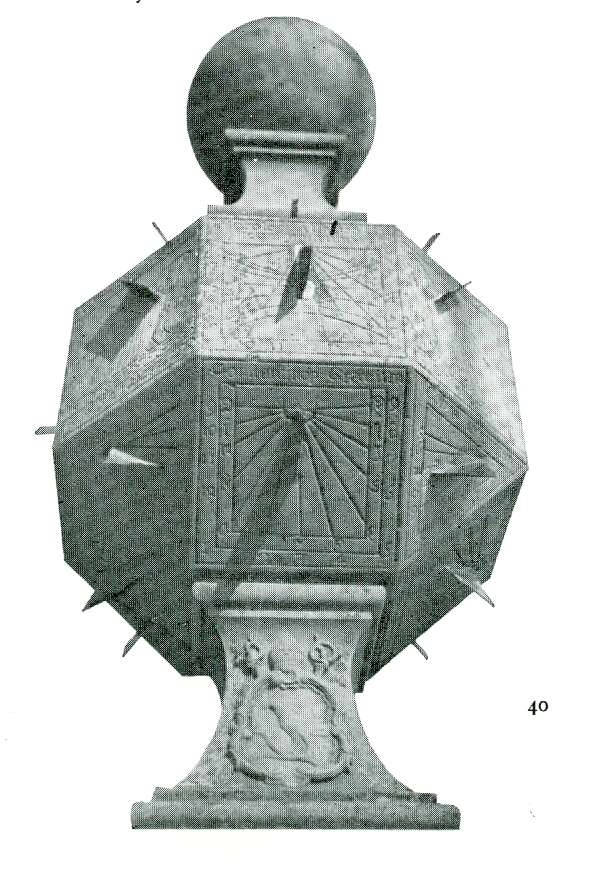

Consider these two exceptional sundials:

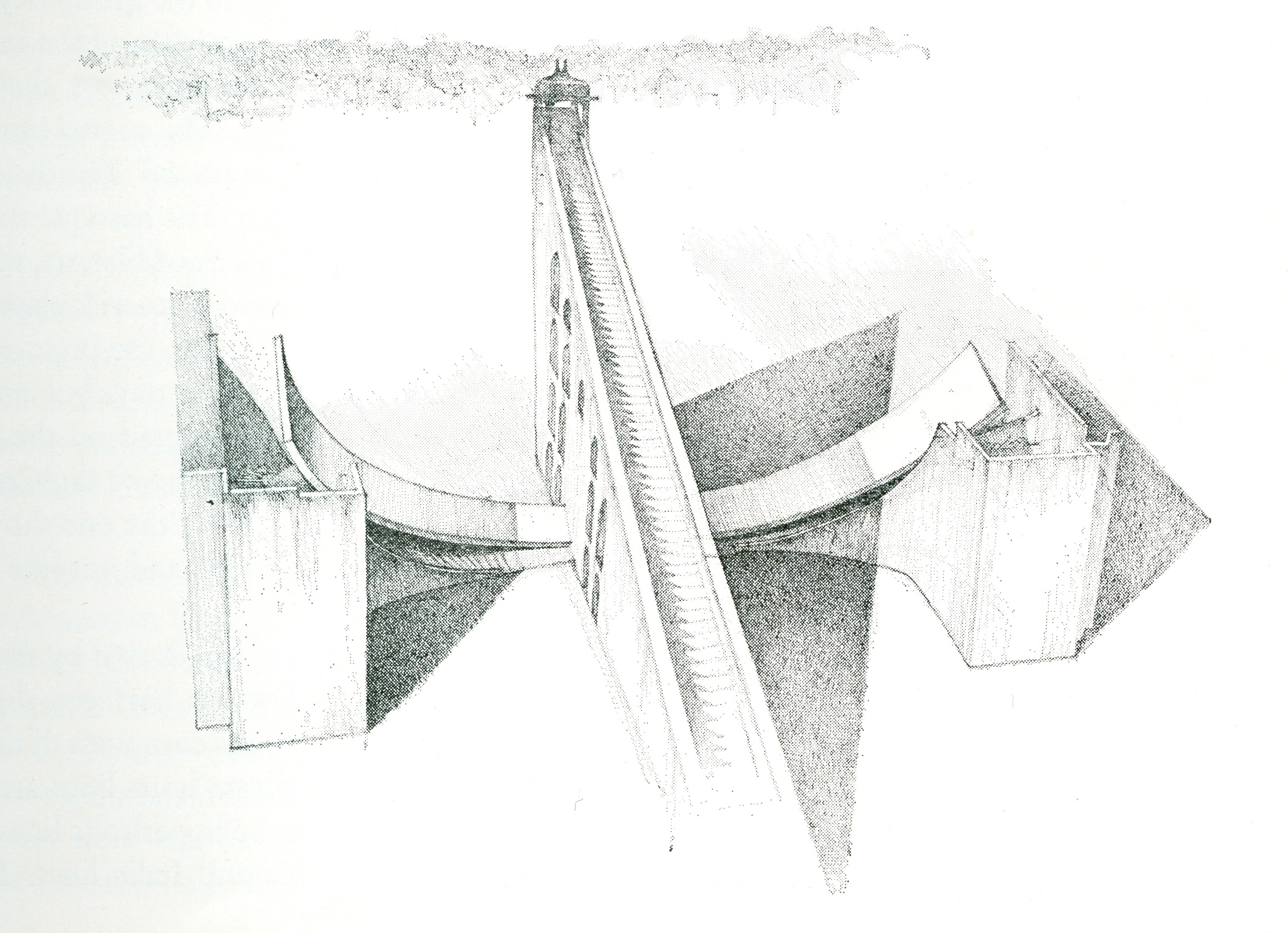

The central part of this giant sundial at the Jaipur Observatory is wide and long enough to be steps ascending to a pavilion! The steps stretch for over 100 feet in length.

(Rohr 119)

(Rohr 119)

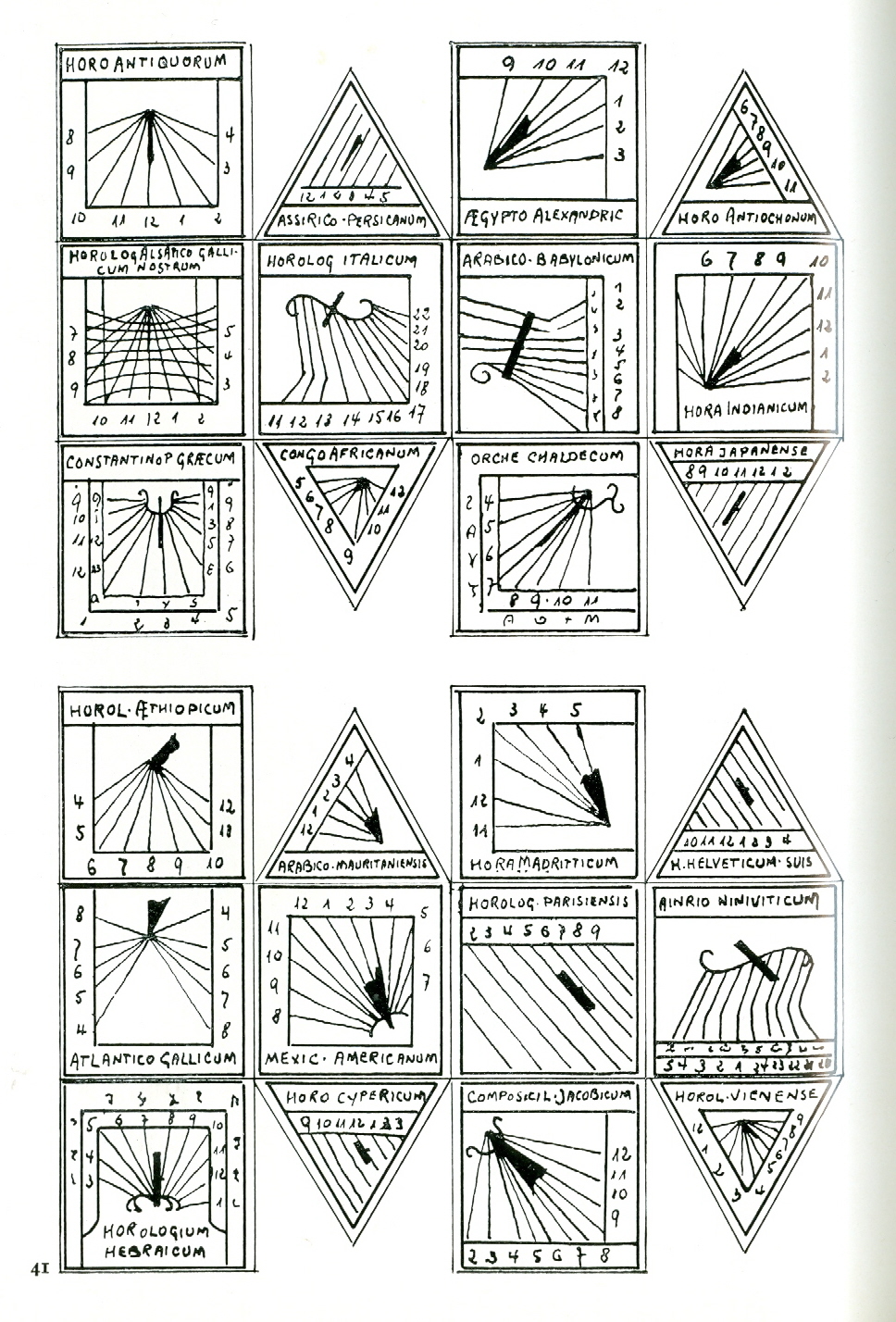

This sundial from Mont Sainte-Odile in France (early 18th century) shows 24 different times, including "Horologium Alsatico Gallicum Nostrum" (the local time, and the face with the most specific markings), "Congo Africanum," "Horolog Italicum," "Hora Japanese," "Horologium Hebraicum," and others. Here's a very clear example of awareness and technology to consider and calibrate other local times. (Below is the author's drawing of each face of the dial as if it were unfolded flat.)

(Rohr 94).

(Rohr 94).

Sundials, like any sort of clocks, can vary significantly in their accuracy depending on their calibration, precision of the marker, and size - bigger gnomons are more accurate than smaller ones since the change in shadow length over the course of the day is larger. They can be very rough approximations of the hour, but modern sundials ("heliochronometer" sounds fancier, but means essentially the same thing) could be accurate to the nearest minute, and they were used up until 1900 by French railroads to uniformly set their clocks (Rohr 16). Keep this in mind for later...

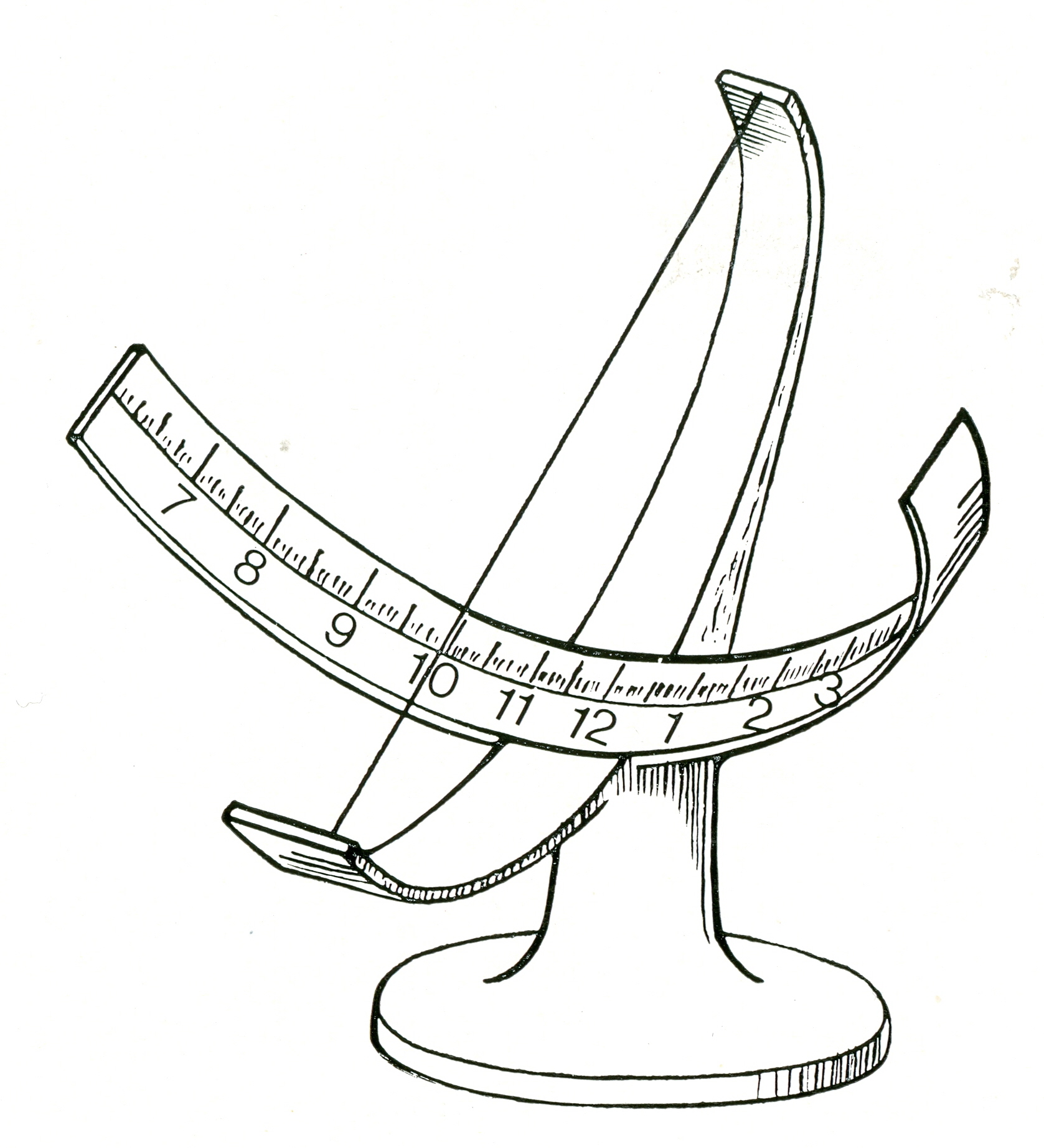

This French heliochronometer consists of a wire set parallel to the Earth's axis.

(Rohr 16)

(Rohr 16)

As for mechanical clocks, they too changed in precision over time. Early clock faces had only one hand that displayed the hour. Another hand to tell the minute was a later development, and a third to show the passing seconds still later. Each additional hand lets the clock display a more precise time. But bear in mind that precision and accuracy are not the same thing. The idea of accuracy requires a truth, in this case, a true and/or accepted time. That is a totally separate idea from precision, which I take to mean the degree of specificity displayed by a clock, as well as its internal consistence (i.e., a clock that displays hundredths of a second but loses an hour every day would not be considered precise).

Even greater precision was made possible in 1967, when the second was redefined to be equal to the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of radiation of the Cesium 133 atom (Audoin 56). 1970 marked the introduction of the most precise time yet: atomic time (TAI, for the French Temps atomique international). It is based on readings from multiple such atomic clocks obtained via GPS (Audoin 263). TAI is so precise that the current time can be known to an uncertainty of +/- 10e-15 seconds (Audoin 263). That's a femtosecond, a millionth of a billionth of a second. A femtosecond is to a second what a second is to 31.7 million years. That's absurdly precise.

An "atomic clock." Get it?

'The Clock main page: Nathan's Thing / Time as Social Concept / Clock as Social Object / (Im)Precision in Time / Yesterday and Tomorrow / To Catch a Train / Experiencing the Clock