Ferdinand Magellan left Spain in 1519 to be the first to circumnavigate the globe. The voyage succeeded in 1522, but for two minor inconveniences: first, Magellan, and four of his five ships, didn't make it - Magellan died en route. Second, despite the remaining captain's careful record keeping, he found that upon returning to Iberia, he and the landlubbers disagreed as to what day it was. Though sure he had counted every sunrise and sunset, he appeared to have gained a day with respect to the home calendar (Bartky 9).

Well, we know what happened. Because Magellan's fleet sailed from east to west - sailing through the Straight of Magellan to the Philippines to the Cape of Good Hope and back home against the direction of the sun's travel - each day spent traveling was just slightly longer than a Spanish day. Really, we would say that he had crossed the International Date Line, but, of course, that hadn't been invented yet. Let's consider that, shall we? If you thought about it, the idea made sense even before Magellan's discrepancy - Nicolas Oresme thought off a "date line" in the 14th century (Bartky 9). Despite this forward-thinking man, numerous instances of date discrepancies occurred.

Perhaps the most famous of these, the one that stuck in the minds of Westerners, is the fictitious case of Phileas Fogg, hero of Jules Verne's 1872 book, Around the World in 80 Days. Fogg, a wealthy whist-playing English gentleman, bets his friends half his worth that he can circumnavigate the world in 80 days. To his dismay, at the end of his 80th day of travel, he has not made it back. But upon picking up a newspaper, he realizes his miscalculation: unlike Magellan, Fogg traveled west to east, losing a day. So, according to the stationary British calendar, he still has a couple hours left. Of course, he wins the bet with seconds to spare (Bartky 26).

Jackie Chan as Phileas Fogg

As a thought exercise, imagine three friends: one travels west to east, one travels east to west, and one stays at home. By the time the two travelers returned, assuming each kept track of his own days, the first would find out that today is yesterday, and the second would see that today is tomorrow. Confusing?

Well, ship captains eventually began changing their "todays" in the Pacific Ocean, roughly along the meridian that runs through the western tip of Russia and the Aleutian Islands, but that didn't really solve the problem officially. Despite the existence of a de facto, if highly variable, date-change line, "There is no international date line," wrote surveyor and geodesist George Davidson in 1901. "There is a theoretical date line through the Pacific ocean dependent on the adoption of a prime meridian through Greenwich or some place in Western Europe" (Bartky 30).

So now the clocks of the world become dependent on the maps of the world, and the politics of how the world draws and measures its maps. The start and end of each day come to rest on politics. So you see, today isn't simply today because of the sun. It's much more complicated than that.

To draw the line, as it were, conferences were held in Rome and Washington, DC. Interestingly, one speaker noted that the adoption of a standard meridian would save time and work (Bartky 76). But we're getting ahead (or is it behind?) of ourselves again...

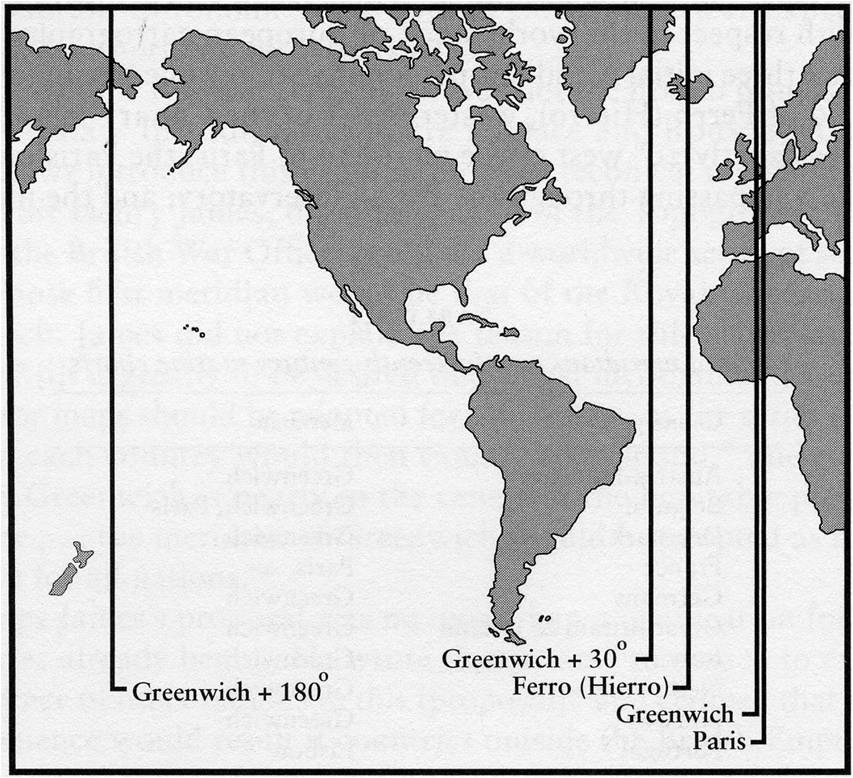

The problem was that different maps were drawn with different prime meridians in mind. So, five main options were considered by Otto Struve:

*Greenwich

*Paris

*Ferro (one of the Canary islands), 20 degrees west of Paris.

*30 degrees west of Greenwich

*180 degrees from Greenwich, its antimeridian (Bartky 38)

(Bartky 38)

(Bartky 38)

Some lobbied for a prime meridian that passed only through ocean so that it would be politically neutral and would not bisect any countries, creating the confusion of positive and negative longitude. When they actually thought about it, they realized that this was ridiculous. No one would pay to build an observatory in the middle of the ocean, and it wouldn't be as reliable anyway. Besides, many nations had adopted the meter, an originally French standard, without loss of pride. Greenwich won out as the Prime Meridian because delegates felt it had the best chance of being actually adopted. 90% of navigators' maps at the time based their longitudes from Greenwich, so it would be the simplest change (Bartky 77).

Forget the hour, minute, and second, for a moment. We didn't even know what day it was until we decided, after getting through this political debate. Think time is inevitable and absolute? Think again!

The Clock main page: Nathan's Thing / Time as Social Concept / Clock as Social Object / (Im)Precision in Time / Yesterday and Tomorrow / To Catch a Train / Experiencing the Clock