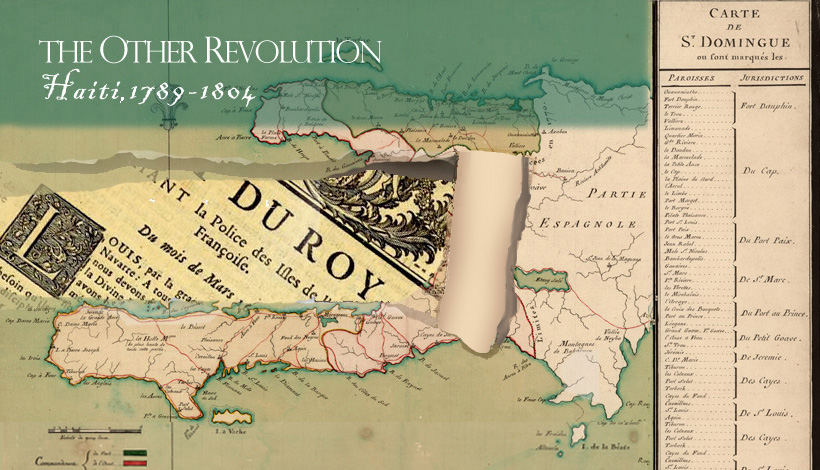

iii. the august 1791 slave revolt |

||

Revolt in the North The August 1791 slave revolt broke out in the northern plains of Saint-Domingue, in the area to the south of Cap Français. Two events are believed to have been of particular significance in triggering the revolt. The first was an August 14, 1791 meeting of slave leaders at the Lenormand plantation, in the parish of Plaine du nord, where the rebellion appears to have been planned and organized. The second was the famous voodoo ceremony on the night of August 21-22 in the forest of Bois Caïman, or “Alligator Wood,” supposedly on the mountain of Morne Rouge. There continues to be much debate among historians as to the exact nature and timing of these events. |

||

Paris dictates full civil rights for free people of color On May 15, 1791, after a highly contentious debate, the National Assembly decreed full civil rights for free people of color born to free parents, effectively enfranchising only a few hundred persons. Nonetheless, white planters regarded the measure as an intolerable intervention in the internal affairs of Saint-Domingue. On August 23, the day after the slave revolt broke out, but roughly two months before news of the uprising could have arrived in France, a planter from the northern province warned a sympathetic Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce that the decree would lead to a massacre of the white population. |

||

Paris interference = Chaos in St. Domingue Exiled and dispersed from the colony in August 1790, the autonomist Saint-Marc Assembly was succeeded by the like-minded Second Colonial Assembly. (The Saint-Marc deputies were pardoned by the National Assembly and allowed to return to Saint-Domingue in late 1791). Both the Saint-Marc deputies and their planter-successors in the Second Colonial Assembly doubtless interpreted the news of the slave uprising as a vindication of their position that the legislature in Paris was causing chaos by interfering in the colony’s internal affairs. More immediately, as this broadside addressed by the Second Colonial Assembly to the king and National Assembly testifies, the planters were desperately focused on securing relief from the government in France. |

||

North reduced to a “pile of ashes” This remarkable letter details the devastation wrought by the August 1791 slave revolt. It was written by members of the Provincial Assembly of the North, the more moderate body of planters who opposed the autonomism of their counterparts in the Saint-Marc (and later the Second Colonial) Assembly. The northern province, they write, had been reduced to nothing more than a pile of “ashes.” “Our fertile fields are flowing with the blood of our brethren.” Over two hundred sugar plantations and the majority of the province’s coffee plantations, the letter indicates, had been entirely destroyed. |

||

Royal backing for the slave revolt? One of the earliest of efforts to explain the slave outbreak of 1791 took the form of assertions that King Louis XVI of France had emancipated the slaves. Indeed, the connection between royalism and insurrection would grow so strong that for much of the revolution the slaves were forced to rebut charges that they were counter-revolutionary allies of the king, the Capetian “tyrant.” In the immediate aftermath of the August 1791 revolt, however, the planters were concerned above all to refute the suggestion that the slaves’ actions had royal backing. Condemning these rumors as the work of “true enemies” of Saint-Domingue, the Provincial Assembly of the North called upon the planters to unite or face “total ruin.” |

||

Emancipation as reward The Gazette de Saint-Domingue began publication during the revolutionary years. The first reference to the August 21-22 slave revolt and its unfolding did not appear until September 3, suggesting an editorial agenda to minimize, if not deny altogether, the reality of the northern planters’ loss of control over their slaves. This report recounts the Colonial Assembly’s decision to emancipate a plantation slave driver named Jean, in exchange for his help in capturing Jean-Baptiste Cap, one of the leaders of the August 1791 revolt. Emphasizing that it was important “in the present circumstances to present this example as a model” to the colony’s slaves, the Colonial Assembly ordered the issuance of a silver medal in the driver’s name. Jean-Baptiste Cap, the elected “king” of Limbé and Port-Margot parishes, had been captured while trying to recruit slaves on a plantation and was broken on the wheel. |

||

Equality between free people of color and whites deemed essential It was not surprising that a white planter community threatened by the events of August 1791 would turn to the free people of color for help, for they had traditionally played a significant role in leading and serving in the colonial militias that chased down fugitive slaves in the mountains of Saint-Domingue. This service lent the free people of color a strategic importance that was recognized in October 1791 by a white planter named Milscent, himself a leader of a fugitive slave militia. Milscent intervened to inform the public that his experience in containing slave resistance is “necessarily linked to the facts that trouble the colony at this moment.” For Milscent, the equality of free people of color with whites was essential to the very preservation of slavery in Saint-Domingue. |

||

| Exhibition prepared by: Malick W. Ghachem (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), guest curator, with assistance from Susan Danforth (Curator of Maps and Prints, John Carter Brown Library). |