v. war and occupation (1793-1798)

|

||

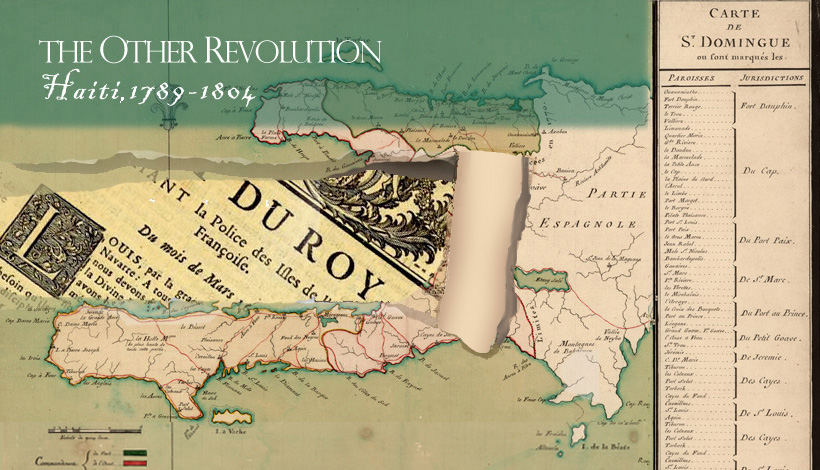

British occupation In September 1793 British forces arriving from Jamaica began a five-year occupation of parts of the western and southern provinces of Saint-Domingue. Sonthonax and his fellow civil commissioners thus found themselves managing a three-way territorial war against both Britain and Spain. In the western and southern provinces this war partly took the form of efforts to secure the allegiance of the free people of color. In this exchange of letters, John Ford, the commander of the British squadron, warned Sonthonax of an impending invasion of Port-au-Prince and promised to safeguard the interests of the free people of color. Sonthonax replied that the city’s white residents were sworn to “remain French or die,” and that they would never again allow their “brothers of color” to suffer the “yoke of barbarous prejudices.” |

||

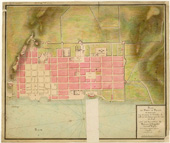

Port-au-Prince under occupation Port-au-Prince became the administrative capital of Saint-Domingue in 1750. Like Cap Français, it was the site of one of the colony’s two high courts, or Conseils Supérieurs. In September 1793, British forces arriving from Jamaica began a five-year occupation of parts of the southern and western provinces. The British started by occupying the southern port of Jérémie and would eventually take Port-au-Prince itself in June 1794. |

||

British invasion, 1793-1798 Military plan. The “British frontier line,” marked in red, refers to the invasion under Brig. Gen. Richard Whyte, 1793-1798. |

||

Campaign to impeach Sonthonax and Polverel In the aftermath of slave emancipation and British invasion in late 1793, a group of planter representatives began an unyielding campaign before the National Convention to impeach Sonthonax and Polverel as “counter-revolutionaries” responsible for the “disasters” of Saint-Domingue. The National Convention succeeded to the Legislative Assembly following the overthrow of the French monarchy in August 1792. In addition to Page and Brulley, the group included Jean-Baptiste Millet (a planter from Jérémie) and the lawyer-planter Larchevêque-Thibaud, deported from the northern province by Sonthonax. In June 1793 Sonthonax and his fellow commissioners left Saint-Domingue for Paris to defend themselves. Sonthonax insisted here that the colony would have succumbed entirely to foreign invasion without his decision to free the slaves, which created 200,000 new soldiers “in a single day” for the Republic. |

||

Sonthonax and Polverel on trial After a series of delays, the trial of Sonthonax and Polverel proceeded under the auspices of the National Convention’s colonial commission, chaired by an antislavery Parisian lawyer named Jean Philippe Garran de Coulon. Known as “the affair of the colonies,” the debates between the planter representatives and the civil commissioners lasted from January to August 1795, and resulted in an acquittal for Sonthonax (Polverel died midway through the trial). The civil commissioners argued that Saint-Domingue had already been in the midst of upheaval before they arrived, due to the brutally repressive tactics of Brulley and company in responding to the unrest in the northern province. |

||

Slave revolution vs. mulatto consolidation One of the chief axes of division within Saint-Domingue throughout the 1790s was that between the slave revolution in the north, led by Toussaint Louverture, and the mulatto effort to consolidate power in the south, led by André Rigaud (1761-1811). Rigaud was a former member of the French contingent that had served in the American revolutionary war. In this letter written from Les Cayes, Rigaud denied allegations that he was entering into negotiations with the British to surrender Léogane, and promised to put up a fight for the southern province. In 1799, Louverture’s and Rigaud’s forces began fighting the War of the South, which would end in victory for Louverture in August 1800. |

||

The pillage of Haut du Cap |

||

St. Domingue émigrés celebrate Bastille Day in Charleston |

||

St. Domingue’s ills blamed on Sonthonax This diatribe against two of the key military figures in Saint-Domingue as of 1795 and 1796 was yet another attempt to explain the breakdown of order in the colony by blaming it on persons connected to Sonthonax. Named interim governor of the colony by Sonthonax back in October 1793, Etienne Maynard Bizefrance de Laveaux (a white officer) rose to the top of the military hierarchy to become a division general by 1795. Jean-Louis Villatte was a mulatto who had been given an important military commission by Sonthonax in 1793 and later led a movement against Laveaux. In the passage shown here Laveaux was singled out for destroying the peace of Saint-Domingue. |

||

View from the metropole - Use force to pacify St. Domingue The restoration of “order” and French sovereignty in Saint-Domingue remained a priority for both the metropolitan government and the planters throughout the years of British occupation and Toussaint Louverture’s consolidation of leadership over the slave revolution. In this address to the Council of 500 (the lower house of the French legislature during the period of the Directory), a former military officer and then-deputy named Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse (1748-1812) advocated the use of force to pacify the “Vendée” of Saint-Domingue. He meant to compare the slave revolution to the royalist, pro-clergy peasant uprising in the west of France in late 1793 that was brutally repressed by the French revolutionary armies, at the cost of tens of thousands of lives. Villaret de Joyeuse would later serve under General Leclerc as commander of the French fleet that invaded Saint-Domingue in 1802. |

||

Contemporary history of the Haitian Revolution Not all metropolitan voices in 1797 were raised in favor of a counter-revolutionary restoration of slavery in Saint-Domingue. Garran de Coulon closed his chairmanship of the commission assigned to investigate the causes of the slave revolution with this report “on the troubles of Saint-Domingue.” Technically a summary of the trial of Sonthonax and Polverel before the National Convention, the report remains one of the most important contemporaneous histories of the Haitian Revolution. In his introduction Garran de Coulon warned that any attempt to return the Haitians to slavery would result in the irreversible loss of Saint-Domingue and the massacre of the colony’s remaining white population. |

||

| Exhibition prepared by: Malick W. Ghachem (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), guest curator, with assistance from Susan Danforth (Curator of Maps and Prints, John Carter Brown Library). |