| Francesca Fiorani: Jeannette D. Black Memorial fellow, 1994-1995 The Enduring Power of Forgery and Imagination |

||||

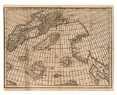

In 1558 a map appeared that seemed to advance knowledge of northern Europe. Its title, Carta da navegar de Nicolo et Antonio Zeni furono III Tramontana l’anno 1380, claimed that it was made by the brothers Nicoló and Antonio Zeni in 1380. The map was an instant success and many copies survive, including one at the John Carter Brown Library. Renaissance mapmakers were determined to represent those areas of northern Europe that Ptolemy did not know about, but lacked reliable sources to meet the demand for news from the European reading public. Caught in the impossible bind between wishing to complete Ptolemy’s world and having little to rely on, mapmakers cherished the new map, even though that meant to trust a fiction. |

||||

The map was first published as a foldout illustration of a book with a lengthy title by Nicoló Zeno (1515-1565), a patrician from Venice, De i commentari del viaggio di M. Catarino Zeno il K. & delle guerre fatte nell’imperio Persiano dal tempo di Ussancassano in quà. Libri due. Et dello scoprimento dell’Isole Frislanda, Eslanda, Estotilanda, & Icaria fatto sotto il Polo Artico, da due fratelli Zeni, M. Nicolló il K e M. Antonio. Libro uno. Con un disegno particolare di tutte le dette parte di Tramontana da lor scoperte (Venice, 1558). The book meant to assert the place of the Zeno family in the history of Venice, listing the public offices of its members over the centuries and relating Caterino Zeno’s ambassadorial post in Persia between 1471 and 1475. Its bulk however was dedicated to the deeds of another ancestor and a namesake, Nicoló Zeno (d. ca 1395), a Marco Polo of the North. The young Nicolo’ had found in his family house letters that told the story of the old Nicoló, an expert navigator who, on his way to England and Flanders, shipwrecked near the Island of Frislanda. Saved by the local ruler, he was hired to command the fleet of Frislanda. Nicoló wrote a letter inviting his brother Antonio in Venice to join him in Frislandia. Antonio came and the two brothers shared duties, honors and adventures there until four years later Nicoló died. Antonio stayed ten more years before returning to Venice but wrote regularly to a third brother, Carlo. It is from these letters written over an extended period of time that the young Nicoló extracted his ancestors’ voyages to Engroneland (Greenland) and to distant islands to the west, Estotiland and Drogero. |

||||

A map survived with the letters. Young Nicoló tells us that “although it is rotten with age I have succeeded quite tolerably” in restoring it and inserted it in the book, but the map was in such high demand that it was also sold separately. Its popularity had little to do with cartographic accuracy and a lot with young Nicoló’s imagination and talent as a writer. He captured the interest of readers eager to learn about northern Europe, its geography, peoples and fables. His main cartographic source was Olaus Magnus’ equally fantastic map of northern Europe (Venice, 1539), the Carta Marina, but many features were fruits of his literary imagination, especially the Island of Frislandia and its mythical ruler who had bestowed honor and power on his ancestors. |

|

|||

| The enchanting power of this Renaissance fabrication was irresistible even for the most rigorous sixteenth-century mapmakers. Giovanni Battista Ramusio reprinted text and map in his Navigationi et viaggi (Venice 1550-1559), a widely-read collection of real and imaginary travels. Girolamo Ruscelli, a Venetian intellectual who published a pocket-size Italian edition of Ptolemy’s Geography in 1561, included the Zeno map among the newly discovered lands, although he detached Greenland from northern Europe. Abraham Ortelius relied on it for his world map of 1564. Gerard Mercator provided his authoritative support by inserting Zeno’s Greenland in his world map of 1569. In the early 1570s the Italian polymath Ignazio Danti used it in a painted map for the Medici Duke. | ||||

| The story of the Zeno map is an instructive and fascinating journey into the contradictions that shaped the mapping of the world in the sixteenth century. Rather than a rigorous scientific project, Renaissance cartography was in reality a hybrid product in which imagination and forgery played as crucial a role as voyages and discoveries. | ||||

On the Zeno Map, see: Philip D. Burden, The mapping of North America: A list of printed maps, 1511-1670 (Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire, Raleigh Publications, 1996) , 31-32. |

||||