PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Timing is everything. When doctoral student Aaron Held came to Brown University in 2012, the opportunities he’s enjoying today had only just begun to take shape. But more than three years into his work, he’s become the vital linchpin between two labs in a diverse collaboration dedicated to disarming a horrible disease. That has given him several chances to learn new techniques and new biology.

Held earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Boston University, studying molecular biology, biochemistry and biotechnology – particularly in stem cells and muscle. He wanted to continue to work in molecular biology and became excited about Brown.

“I really liked the atmosphere here,” he said. “When I came to interview all of the graduate students I talked to seemed pretty happy and that they were doing well, publishing papers and being productive.”

He joined the lab of biology Professor Kristi Wharton. At the time, she and several colleagues were just moving into an urgent area of research: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A group of scientists at Brown had figured out they could create accurate models of the incurable, degenerative neuromuscular disease in organisms such as flies and worms. They were hatching a plan to perform massive genetic screens of these ALS models to find and study random, natural mutations that might keep the disease in check.

Like more than a dozen graduate and undergraduate students who’ve become involved in the ambitious challenge, Held grabbed a hold of the banner and has helped to carry it forward. Senior Sarah Grosser in the lab of neuroscience Professor Anne Hart, for example, has been creating worm models of ALS, and fellow graduate student Amanda Duffy in the lab of neuroscience Professor Justin Fallon is using automated behavioral monitoring system developed by Professor Thomas Serre, to observe disease progression in ALS mouse models.

Labs ‘held’ together

“Both labs bring very different perspectives to the table on how to do different experiments or answer different questions.”

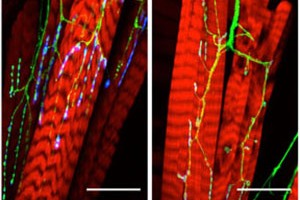

Held’s work unites two labs in the collaboration. Following a rotation in the Wharton lab examining genes known to control strength of the junction between a motor neuron and its target muscle, he did a rotation to learn electrophysiology techniques in the lab of neuroscience Professor Diane Lipscombe, who studies neurons in the spinal cord and elsewhere. With biology Professor Robert Reenan generating ALS mutations in flies as a model and collaboration building between the Wharton and Reenan labs, Held’s newly found skills in electrophysiology provided an important means to measure the functional consequences of the ALS mutations in flies, Wharton said. Continuing his training with Lipscombe in electrophysiology makes him a vital link between the Lipscombe and Wharton labs.

“Aaron has been really terrific and that has helped with the collaboration, bridging between Diane’s lab and my lab,” Wharton said.

Meanwhile, in other work on the project, Held has learned other things. He’s gained significant experience in how to make use of the sophisticated genetics of Drosophila to probe questions involving the nervous system and he’s learned skills such as how to write computer code to run advanced sequencing experiments on different genetic strains.

Working across two labs has definite benefits, Held said.

“Both labs bring very different perspectives to the table on how to do different experiments or answer different questions,” he said. “It gives you a broader base of knowledge and approaches to work with, which is pretty awesome.”

The zeitgeist of 2014 also gave Held the unusual opportunity of taking the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge with the University president. He stood right behind Christina Paxson and among other brave volunteers for the cause.

The chill didn’t bother him much.

“I did grow up on the Cape, where the water is pretty cold,” he said. “It’s not too different from that.”

But in many important respects, Held’s time at Brown has been marked by novel learning experiences.

“It’s been challenging,” he said “but also very rewarding.”