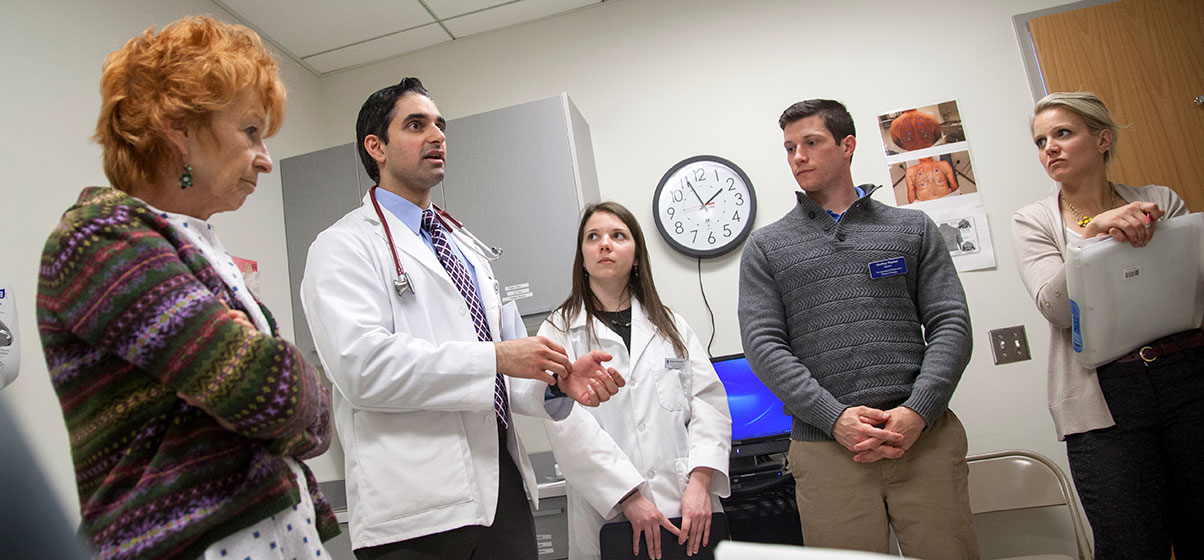

With "patient" Susan to his right, Medical student Anshul Parulkar talks about her case with URI pharmacy student Stephanie Komjian, URI physical therapy student Geoffrey Phaneuf, and Rhode Island College social work student Rebecca Sumner. Images by Nicholas Dentamaro

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Susan, a middle-aged state government accountant, sits in her gown on the examination table, surrounded by a care team. She’s come for her annual checkup, complaining of back pain from a herniated disc diagnosed a year ago.

The team’s two nurses take Susan’s vital signs and ask her to describe her pain. The doctor listens to her breathing and measures her pulse. The social worker asks about life, the physical therapist inquires about the back pain, and the pharmacist asks whether she is taking other medications or has allergies.

Along the way, everyone gently probes for details about symptoms and how she’s managed them. Susan reveals that she only received a month’s supply of the opioid painkiller Percocet a year ago. After that, as her back continued to nag her, she bought the medicine from friends. More recently, to save money, she’s been buying heroin in the park. Twice a day she takes the drug.

“I need it before I go to work,” Susan says.

The team points out the dangers of opioid dependency, but they don’t judge. Instead, they ask for more information as they carry out the routine steps of an annual physical. They ask about her goals for her care. She wants options other than heroin, she says, provided the team can make the pain go away.

“I don’t want to be on this stuff, you know,” she says. “I did what I had to do.”

Parulkar listens to Susan's breathing while she explains why she's begun using heroin.

In reality, Susan is an actor and the care team is composed of students at institutions from across Rhode Island. At the moment, they are still training for the roles they play in this workshop convened by the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Under the observation of a Rhode Island College social work professor, they are practicing a “patient encounter” that is quite deliberately typical of the state’s opioid addiction epidemic.

Collaborative care

In total, two April workshops at Brown served about 500 students from the medical school, the University of Rhode Island’s schools of nursing, pharmacy and physical therapy, and Rhode Island College’s schools of nursing and social work. The principal organizer is Dr. Paul George, associate professor of family medicine at Brown.

George says it was especially important this year to focus on training students to deal with the opioid epidemic because of how pervasively it is ravaging the state. With dozens of Rhode Islanders dying in accidental drug overdoses every month, it seems almost inevitable that these students will have both the opportunity and the obligation to pull addicted patients back from the brink to save their lives.

“Opioid misuse is a growing problem in the U.S., and I think Rhode Island is number one in the country as far as recreational drug use,” George says. “This is something that our students in all the health professions are going to see fairly regularly.”

At the workshop, the team leaves Susan for a moment to discuss a care plan out in the hall. Brown medical student Anshul Parulkar of Northborough, Mass., takes on the role of moderator as each member contributes ideas. They want to treat her addiction, but they respect that she wants to address her pain. They decide to order a new scan to confirm the herniated disc. They’ll prescribe a new, lowest-possible dose of Percocet because they hope that will keep Susan engaged in a comprehensive pain management plan that will not rely on drugs. That will center on an eight-week course of physical therapy and other non-pharmaceutical tips for managing pain. They’ll also provide counseling to address her addiction — an important resource because she doesn’t want to confess her secret to her friends or family.

Back with Susan, the students don’t moralize or threaten. They empathize and seek to persuade. Parulkar resumes counseling her about the danger opioid dependency poses to her health and tells her that even if she does have to take a bit of a harder road to managing her pain, staying off of heroin or high doses of other opioids will be much better for her. For instance, he points out, the drugs slow breathing, reducing oxygen intake. Susan has reported that she’s a smoker, too.

“One of the reasons we’re trying to be as conservative as possible with this approach is so that you are able to continue to breathe,” Parulkar says.

Then things get real

In the next session, the patients are real. Dr. Josiah Rich, a Brown professor of medicine and of epidemiology, takes the stage with two Rhode Island residents, both recovering from heroin addiction, to speak a full auditorium of workshop students. The patients, “Ike” and “Rhonda,” don’t hold back in sharing how terrible it was to be “chasing the drug.”

Honestly told, each patient’s story evokes and tests the students’ sympathies. Ike warns them that desperate people with addiction can be dangerous and violent. One of his stints in prison came from an incident where he walked, filthy and sleepless, into Rhode Island Hospital’s emergency department and attacked a health care worker there after she made him feel disrespected.

“The look that she gave me and her tone of voice made me snap, and I just grabbed her by the hair and pulled her over the table,” he says. “I didn’t hit her. I just poured on all kinds of ‘B’s’ and ‘Mother Fs.’ I went to jail and did a year for that.”

Rhonda says she sustained herself as a serial shoplifter. She was shot in the chest within months after she became addicted to cocaine and started hanging around on streets where her mother had implored her to never go. Soon after, she switched to heroin.

Both Ike and Rhonda say they knew they were doing bad things, but once the heroin had taken hold, they didn’t care because they were getting what they needed. They could only do what would get them their next hit. Their paths to recovery, however, were cleared by people who could see past the disease and regarded them as people who still needed and deserved help.

“Please try to be compassionate,” Rhonda says. “I think that goes a long way. People want to feel like they aren’t being looked down on like a piece of crap. We just want to feel some love and attention.”

Timely training

These were timely encounters and exercises for Parulkar and his fellow medical students. They’ve studied opioid addiction in textbooks and watched videos. It’s in his lecture notes, and it’s been on his exams. But this year, his third, he’ll head into the doctors’ offices, hospital rooms and emergency departments of Rhode Island to observe and participate in real patient care.

It was important to hear the stories of Ike and Rhonda, Parulkar says.

Parulkar said the workshop will help him be a compassionate advocate for people with opioid addiction.

“It made a very strong impression. I will try to be especially compassionate when dealing with a patient who has opioid addiction. I think I’ll be able to advocate for them a lot better. I think I’ll be able to relate to them more.”

Two more workshop sessions follow. In the next, the team that met Susan reunites to discuss the case of another patient, this time presented on paper. A homeless house painter shows up at the Rhode Island Free Clinic with a nasty cough and a history of heroin use. The students infer what they are supposed to: HIV is a distinct possibility for this patient and with it, tuberculosis. His care needs — both immediate and long-term — will be complex, and so will finding the resources to help him.

Before the afternoon is over, the students also learn how to administer Naloxone, or Narcan, the seemingly miraculous drug that reverses opioid overdoses. They not only have to know how to administer it, but also how to teach patients —and their friends of loved ones — to do so. Overdoses are not rare in Rhode Island, but they don’t often happen with a health care professional already on the scene.

“One of the things that’s happening very frequently now is that Naloxone is being co-prescribed with opioids,” George says.

That kind of complexity, in which a prescription for pain comes with a second prescription to mitigate the danger of the first, is just part of why the state’s future health care workers are being trained together by the hundreds at Brown.