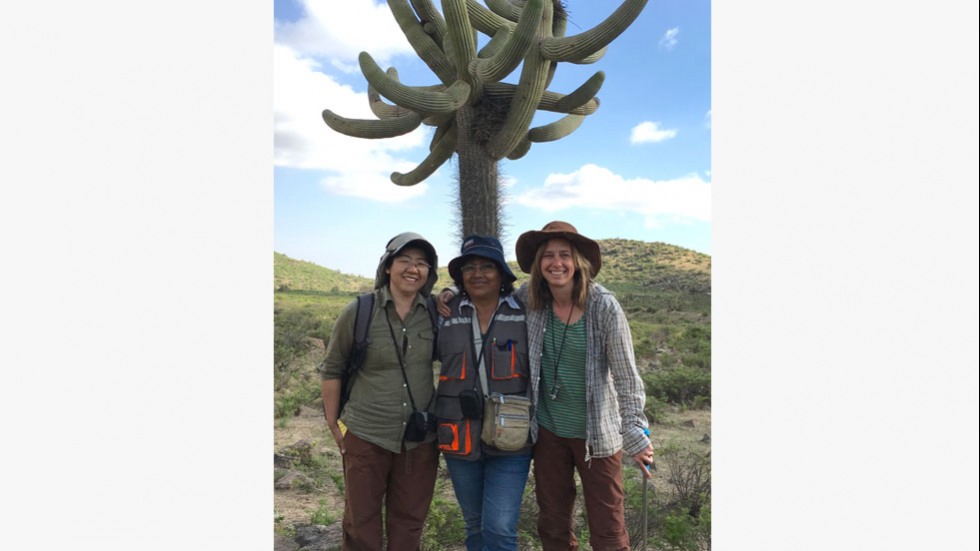

As part of research that won her recognition from President Obama at the White House May 5, Erika Edwards took her class to the desert mountains of Peru in March to survey patterns of plant growth and different means of photosynthesis. Erika Edwards

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Here are two things that Erika Edwards picked up this spring: some dusty dead branches in Peru’s Atacama Desert, and in-person plaudits for her Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers at a White House ceremony with President Barack Obama.

And yes, they have everything to do with each other.

Both the award and Edwards’s expedition, conducted with the 12 undergraduate students in her Biology of Desert Plants class, stemmed from research funded by the National Science Foundation since 2013. Edwards investigates how a lineage of plants called portulacineae have evolved special means of photosynthesis to cope in situations where regular photosynthesis isn’t feasible. This year the White House honored her work and her teaching with the nation’s highest award for young scientists.

“We congratulate these accomplished individuals and encourage them to continue to serve as an example of the incredible promise and ingenuity of the American people,” Obama said in a statement in February when he announced all 105 PECASE award winners, including Edwards.

In pursuit of photosynthesis

The special photosynthetic means that Edwards studies are known as “C4” and “CAM.” She pursues them through deep time and around the globe to learn how, when and where they came to be.

Everyone learns in school about the garden variety, or C3, brand of photosynthesis: Plants use chlorophyll as they take in carbon dioxide, light and water to make sugar. But when water is scarce, plants prevent it from escaping their leaves by closing up the little holes called stomata that they also use to take in carbon dioxide. C4 and CAM are ways of making the most of the carbon dioxide they can get when threatened by drought (or if carbon dioxide is scarce in the plant for some other reason).

In CAM, the focus of the Peru expedition and PECASE award, the scheme evolved this way: Plants open their stomata at night when temperatures are cooler, rather than during the day, which means they lose less water. They then store the carbon dioxide in chambers in the leaf for photosynthetic use in the day when there’s light. That may sound simple, but it requires a logistical coordination of many different enzymes and structures within the leaf that must have required many distinct evolutionary changes.

“We don’t really know anything about how this system evolves,” Edwards said. “The purpose of the grant is to start to suss that out, by focusing in on one group of plants that we think has evolved CAM many times over the last 40 or so million years. We have also identified many species that are neither C3 nor strictly CAM — rather, they have a photosynthetic system somewhere in the middle.

“The goal is to place all of these species in their phylogenetic tree and reconstruct the order of events during CAM evolution,” she said. “What happened first? Next? What sorts of environments select for CAM? What non-photosynthetic plant traits are essential for the emergence of a CAM system?”