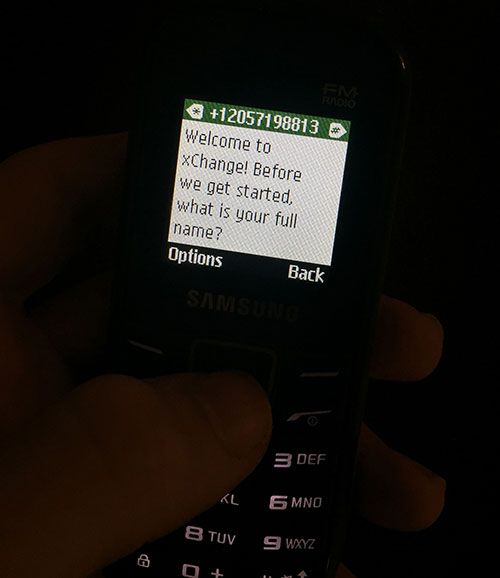

Farmers in remote locations can often have trouble finding buyers for their crops. Wilson Cusack developed a text-message platform that connects farmers and buyers.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — For most students a senior thesis represents a valuable learning exercise and the culmination of several years of careful study. Brown University senior Wilson Cusack’s was certainly both of those, but it’s also about to be an international agricultural technology project sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

For his honors thesis, Cusack developed a text message platform that connects farmers with goods to sell to buyers looking to purchase them. He thought the platform could fill a need for rural farmers in the developing world who often have trouble finding buyers and getting a fair price for what they grow. The Gates Foundation agreed, awarding Cusack and his company, Trade, $100,000 to implement the platform in Ghana.

For the 23-year-old native of Grand Rapids, Michigan, the grant helps to launch an idea that started cooking before he got to college. “It’s kind of amazing how full-circle it’s come,” Cusack said.

During a gap year between high school and college, Cusack spent some time living in Guatemala and India where he worked on various development projects. He saw firsthand the crushing poverty faced by many small-scale farmers in the developing world.

“Pretty much everywhere I went in India, agriculture came up as a problem,” Cusack said. “That year, on average, a farmer committed suicide almost every 30 minutes.”

He spent a lot of his time in India visiting markets and talking to farmers. He started to get a sense that many farmers — especially those living in remote locations — were simply having trouble finding buyers for their goods. And when a farmer did find a buyer, it was usually a trader who would pay a fraction of what those goods were actually worth and then resell them in a market for a huge profit.

“I had this really simple idea,” Cusack said. “Why can’t farmers text in to a platform and say what they want to sell and be connected with a buyer who texts in to say what they want to buy?”

Such a platform, if widely adopted, could bring together farmers and buyers who would never have crossed paths otherwise. It would also bring a bit of transparency to the pricing of goods, potentially helping farmers get more for their crops.

Cusack kept the idea in mind and started reading up on commodity markets and supply chains. The summer before his sophomore year, he worked with Eleni Gabre-Madhin, an economist who had led a team that created Ethiopia Commodity Exchange, the second commodity exchange in Africa. After coming to Brown as a transfer student in 2013, Cusack interned at the agriculture technology company FarmLogs and with the food-processing firm Cargill.

“I spent a lot of time trying to get people to convince me that this cell phone platform wouldn’t work,” Cusack said. “But people just convinced me more that it would work and that it was a good idea.”

He decided he would pursue the idea as his honors thesis, working with professors Rodrigo Fonseca in computer science and Andrew Foster in economics.

Cusack set to work developing the code for the platform, which he designed to make transactions as quick and easy as possible. In just a few texts, farmers can enter the market with what they have to sell and how much they want for it. Buyers can do the same for what they’d like to buy and how much they’ll pay. A matching algorithm then finds the best pairings based on quantities to be traded and the asking and sell prices.

Once he had a working version of the system, the big question became whether people would actually use it, and there was only one way to find out. This past January, Cusack headed to Ghana to see if he could talk some farmers and traders into using the system.

Field test

Cusack chose Ghana for several reasons. English is pervasive there, so language wouldn’t be too much of a problem. The country also has 116 percent cell phone penetration — more cell phones than people. Professors at Brown and elsewhere helped put Cusack in contact with professors and students in Ghana to help get the project off the ground.

It didn’t take long to find a few farmers and traders willing try it.

“I went to villages and told farmers that I would buy from them right then, paying above market, if they used the platform to facilitate the transaction,” Cusack said. “I then went to buyers in the urban markets and told them that I would sell to them right then, below market, if they used the platform to facilitate the transaction.”

He then told everyone he’d worked with that if they had anything they wanted to buy or sell over the next few days, they could use the platform on their own. That was really the big test: Would people use the platform without Cusack standing in front of them as the buyer?

They did.

Over the next week, farmers began independently texting their goods and asking prices to the platform. Buyers texted their bids, and in short order the system had facilitated the trade of around 500 kilograms of maize.

“People who had used it were excited about it,” Cusack said. “In that respect, the trip was a really big success.”

Now that he knew he had a platform people would use, it was time to refine the matching algorithm and write up the thesis. He wanted to add a parameter to the algorithm that took the locations of buyers and sellers into account when making a match. He also wanted to make sure could run efficiently and make matches quickly. That made the algorithm much more complex than the original.

“It was funny because when we started this we wondered if there was really enough technical meat here for this to be a computer science thesis,” Cusack said. “But when I came back in the spring, I realized I actually had a real-deal computer science problem because I could have spent an entire year just thinking about the matching algorithm.”

Cusack is still working to refine and expand his algorithm. He’s now working to loop transporters into the mix so they can bid to move goods once deals have been struck. That, he says, will be a critical new part of the platform moving forward.

Grand Challenges

In the midst of working on the project, Foster mentioned that the project would be a nice fit for the Gates Foundation’s Grand Challenges Explorations program. One of the challenges in the latest round of the program sought projects that dealt with the delivery and use of digital financial services.

Cusack applied and the project ended up as one of 43 projects selected for funding out of nearly 1,400 applications.

With that funding in place, Cusack will move to Ghana this summer to set up a full-scale pilot of the project. The money will cover his living expenses and the cost of hiring technical and managerial staff, among other things.

It will make for a whirlwind few months.

“I'm packing a lot of big life stuff in,” Cusack said. “I graduate May 29th, get married June 4th, and then will move to Ghana full-time end of July.”

He admits that prospect of moving to a new continent to set up a complex project is mildly terrifying, but having the support of his fiancée helps a lot, he said. He had been planning to do this whether the Gates Foundation supported it or not, but the funding makes things much easier.

“The stamp of approval is really helpful,” Cusack said. “There’s suddenly a bunch of people who didn't want to talk to me before who do now. It also helps to validate that this is maybe a decent idea, and that someone outside my mom and me believes in it.”