PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When clashes between government protestors in Syria and the regime of Bashar al-Assad spiraled into civil war, many Syrians took up arms — others, like Dr. Khaled Almilaji, countered the violence with a different manifestation of courage. He shipped in medical supplies, built hospitals, vaccinated children and treated the wounded, even while he was a prisoner of the regime.

His latest step to fight the escalating horrors in his country is to earn a master’s in public health at Brown University. As the conflict has grown in scope and complexity, Almilaji’s humanitarian responsibilities have as well. He’s committed to gaining the additional education to provide the best care for his country. That means not only continuing to solve urgent problems, as he has done in myriad ways, but also studying how to build, assess and improve those systems for the long term.

“The international NGOs have been doing a great job in Syria,” said Almilaji, who moved from Turkey to Providence in September to begin his studies at Brown, supported by Provost Richard Locke and the School of Public Health. “But they are still working in a concept of relief. After five years, we really have to step out and look at what we are doing, improve our performance and prioritize our activities for a long-term and consistent way of doing things.”

A young doctor before the war

Almilaji grew up in Aleppo, the devastated metropolis that is now the focal point of the conflict. Many members of his family worked in health care. His uncle, a surgeon, operated a hospital and lived on the top floor. As a teenager, Almilaji would accompany his uncle on rounds and developed a desire to practice medicine.

After graduating from medical school in Aleppo in 2006, Almilaji earned a residency at a small military hospital in the coastal city of Latakia. He focused on otolaryngology because of how it combines medicine and surgery. He also took a side job as a lecturer and sales representative for the French drug company Sanofi.

In early 2010, Almilaji earned another residency in Germany, where his uncle had trained. He couldn’t leave immediately, though, because he needed to first study the language.

Syria’s troubles started in early 2011 in the southern city of Daraa. The government’s harsh treatment of young protesters angered their families, Almilaji said. As the crackdown widened, the cycle of protests and brutal government reprisals spread north to cities such as Homs. When it reached Latakia, a whole neighborhood became besieged as residents held off intelligence and police forces, he said.

That’s when Almilaji first became a humanitarian responder. He helped to send money, food and medical supplies into the neighborhood. By May 2011 he began treating injured protesters in improvised hospitals set up in Homs and other cities. Activists couldn’t go to regular hospitals for fear of arrest or execution.

Arrested, tortured and forced to flee

In September of the same year, after Ramadan, Almilaji traveled to Damascus to resign his sales job. His involvement in supporting the protesters, he said, presented too great a risk for his colleagues and the business. With his resignation tendered, Almilaji headed back onto the street to meet friends.

“In the street we were arrested like in a Hollywood movie,” Almilaji said. “The cars were everywhere and we were surrounded by people with guns.”

The police took Almilaji to a cell built for perhaps four people but holding 25. For two weeks, they tortured him.

“I was electrified,” Almilaji said. “They broke my finger, they broke my rib.”

Others would be taken away from the cell and brought back bloodied.

Yet even after they hurt him, the guards still depended on him to treat the other sick and injured prisoners they were torturing, Almilaji said.

After they were released, several fellow prisoners called Almilaji’s family members to tell them he was still alive, defying explicit warnings from the police.

In early 2012, after six months of captivity, the police released him to make room for more militant prisoners —but not without a warning to halt his support for activists and rebels.

“They told us that they hoped that we learned from this lesson,” Almilaji said. “Nobody who was released just gave up. When you see the savagery and the torture in the prison, you will never stop fighting this regime.”

With main roads cut off, it took seven days to get to Aleppo from Damascus, but Almilaji managed to return to his family. There he found that the relatively quiet city had become the new home of internally displaced refugees from the more tumultuous cities in the south.

People trusted Almilaji because he had been arrested. With donations from contacts around Syria, he and his family worked to help find new homes for the displaced families. When intelligence agents raided a friend’s house, Almilaji knew he would soon be back in trouble, too.

“Usually when you are arrested for the next time, it will be the last time,” Almilaji said.

He fled to Turkey. He joined a cousin in Gaziantep near the border.

From prisoner to leader

Flooded with refugees and wounded rebels, Turkey needed doctors who could speak to the Syrian patients, sometimes to mediate difficult discussions about needed amputations. The newly exiled Almilaji soon filled in, providing translation for the Turkish medical staff.

He didn’t just do it himself. He formed a team to cover a network of about two dozen hospitals in eight cities along the border. The team also connected patients with local charities and social services.

In 2012 Almilaji began leading the Turkish medical branch of a large Saudi charity. He led an effort to procure ambulances for the Turkish Red Crescent to help transport wounded people from the border to Turkish hospitals and engaged in planning projects to improve Syrians’ access to care.

In March 2013, Almilaji landed a new opportunity. The Syrian opposition, which held significant territory by that time, had formed a humanitarian arm called the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU). They wanted him to lead its medical office.

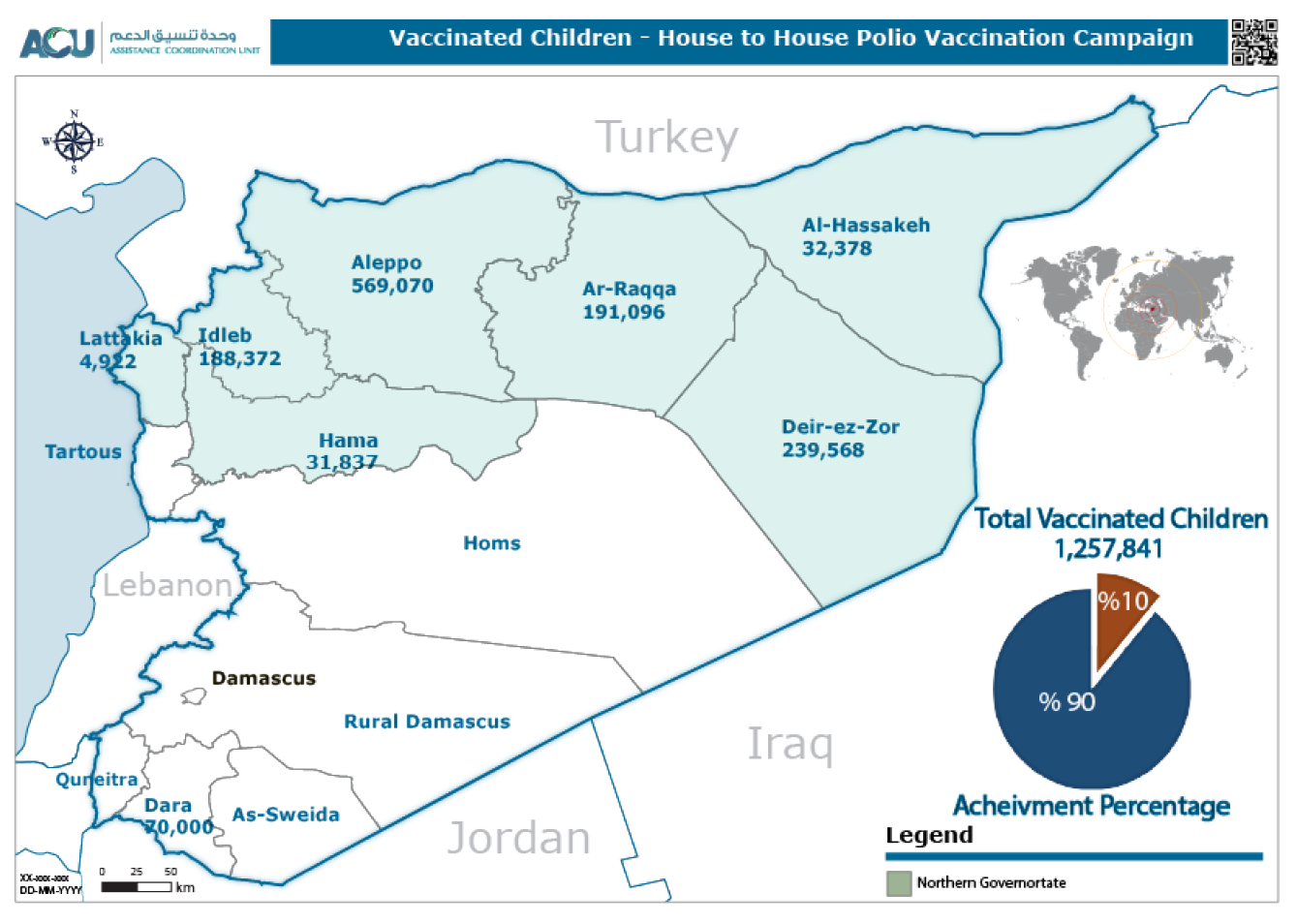

A map shows where the Assistance Coordination Unit was able to vaccinate children against polio.

Courtesy Khaled Almilaji

Almilaji helped to coordinate hospitals and manage medical resources in opposition-held areas of Syria to provide faster service to the wounded, who sometimes died on the way across the border. But Syrian hospitals were themselves coming under attack. So one of Almilaji’s projects at the ACU — one he acknowledges was controversial because of the expense — included starting to build underground hospitals.

Preventing polio

In June 2013 Almilaji met with representatives from the World Health Organization, which had become worried about the spread of disease. Almilaji suggested a health surveillance network among hospitals and clinics in Syria. The WHO and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided support and training for the team that would staff the new Early Warning Alert and Response Network (EWARN).

A few months later, the network discovered an outbreak of polio after transporting suspected viral samples from patients in Syria to a lab in Ankara for confirmation. Despite some complex bureaucracy, the WHO and Turkish government provided vaccines to the ACU. Employing thousands of workers over several rounds of vaccination, the network’s Polio Control Task Force managed to vaccinate 1.25 million children and to suppress the spread of the virus.

“We didn’t have any new cases after the first round,” Almilaji said. “But we had to repeat the campaign every month. You need two years of campaigns to make sure all children under five were vaccinated — newborn and older children who were missed.”

The U.S. and French governments and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation helped to fund latter stages of the campaign. The foundation also became a donor supporting EWARN.

As he was working in Turkey and Syria, Almilaji began to meet and befriend volunteers from Canada, who were helping to train medical staff. Together with Dr. Jay Dahman, paramedic Mark Cameron and Dr. Ammar Zakaria, Almilaji founded the Canadian International Medical Relief Organization in 2013. CIMRO has provided direct medical aid and has been working with the United Nations and other organizations to bring medical and relief supplies into Syria and to document and monitor the needs of internally displaced refugees in the country.

Almilaji in 2012 with Dr. Jay Dahman and paramedic Mark Cameron, with whom he founded a new humanitarian organization.

Courtesy Khaled Almilaji

CMIRO has also continued the work to raise money for underground hospitals near Hama and Idlib. Construction is now complete, and Almilaji expects them to open this year.

In 2014, Almilaji left the ACU to work with CIMRO full-time, handing over EWARN to other, trusted hands.

Coming to Providence

Among the key supporters who have aided Almilaji’s work has been Dr. Annie Sparrow, a critical care pediatrician and assistant professor of global health at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Her husband is Brown alumnus Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch and board member at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. Roth is also a key participant in the Provost’s effort to identify displaced Syrian scholars.

Roth and Sparrow suggested he consider studying public health at Brown. Including Almilaji, the University has identified and extended support to three displaced Syrian scholars and their families during the past year.

With the connection made, School of Public Health Dean Terrie Fox Wetle met with Almilaji. It had been a long five-and-a-half years since the days when he was a young ear, nose and throat trainee. Since then, circumstances and the will to respond to them had made him a prominent practitioner of humanitarian public health.

“I have done the fieldwork,” he recalled telling Wetle. “I got a good result but I didn’t know that I got the good result because I was lucky or I was doing it in the correct way. I needed really to know what are the standards of public health, what are the principles.”

That’s why Almilaji is now in Providence taking classes such as “Burden of Disease in Developing Countries,” epidemiology and biostatistics. He has been, after all, working to manage disease outbreaks and to coordinate massive amounts of medical information about a large subset of his country’s population. CMIRO now has a contract with the World Health Organization to coordinate health information across field hospitals within Syria.

As he walks the campus of Brown and the streets of Providence, with a major election looming in the United States, he said he hopes that people won’t take democracy for granted. It’s something that both Americans and now Syrians have sacrificed and suffered to obtain.

“Hundreds of thousands of people now are killed, hundreds of thousands are in the jail, and hundreds of thousands are missing,” he said. “Those people, they really want to live in a country where they have democracy and their human rights respected. Don’t underestimate what you have in the U.S. because it’s really valuable. For us, we need to establish everything from scratch.”