PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — For scores of years after the first medical school opened in China in 1886, the country progressed in building a medical education system for its fast-growing population. Then 50 years ago, it not only came to a screeching halt, but to a full reversal with the Cultural Revolution.

“Indeed, throughout the decade in question (1966 to 1976), all extant medical schools were effectively shuttered and their faculty disbanded,” write the authors of a new paper describing the history and current status of China’s medical education system. “It was only in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution and the passing of Chairman Mao Zedong in 1976 that the medical education enterprise embarked on a slow recovery process during which some of the schools affected were allowed to reopen.”

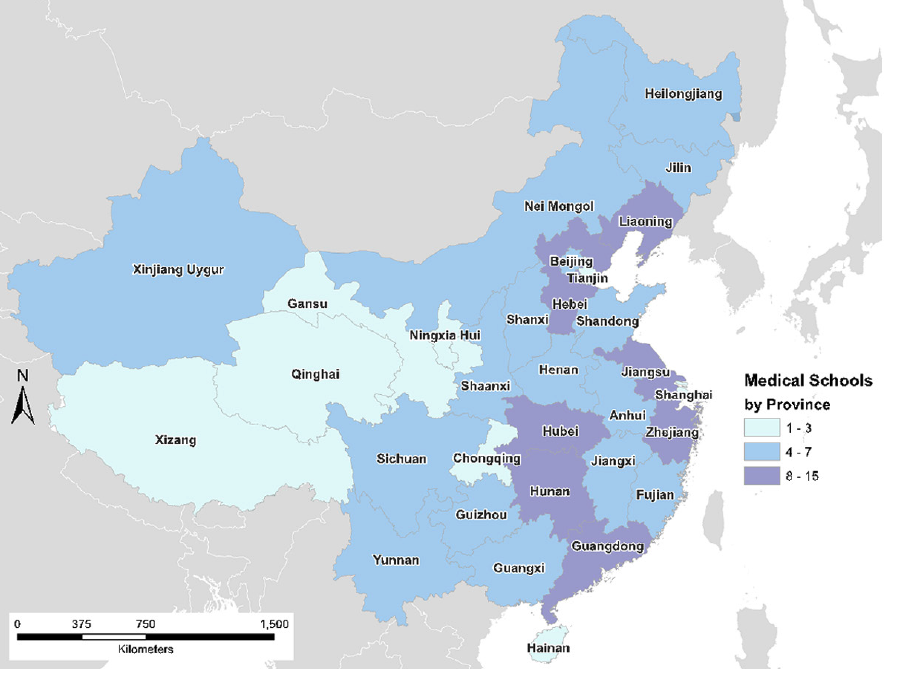

Since then, the pace has quickened considerably to the point where the country has more than 2.1 million practicing physicians and more than 167 civilian medical schools enrolling about 64,000 students. The restoration of a large national system for undergraduate medical education in just 40 years is remarkable, said study corresponding author Dr. Eli Adashi, former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University.

“They had to go from 0 to 60 in three seconds,” said Adashi, who has visited China many times since 2008, often to study and to advise colleagues within the system. “They had to cover a lot of ground, and since they are trying to catch up to the rest of the world, they had to go about it fairly quickly. For the hardships and difficulties and hugeness that characterizes China, they’ve done pretty well on the medical school part.”

In addition to Adashi, the authors of the paper in the American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology are Dr. Nan Du, a graduate of Brown University’s Alpert Medical School now at Yale, and Dr. Huanling Zhang of Fudan University in Shanghai.

Peculiar paths

Despite China’s overall progress, two overarching peculiarities remain in the system by which China’s Ministry of Education produces its physicians, Adashi said. One is the complex diversity of paths an aspiring doctor can follow to gain medical training and become a practicing doctor. The other, which Adashi said is a more serious concern, is a near-complete lack of standardized residency programs, or graduate medical education.

Chinese students can follow many paths to becoming a doctor, including curricula lasting three, five, seven or eight years. As in most places around the world (except the U.S.) enrollment in a medical education program occurs in lieu of obtaining a four-year non-medical undergraduate college education.

Instead, the vast majority of Chinese medical students (about 58,000) attend a five-year program after high school to earn a bachelor’s degree. Then they serve in a one-year clinical internship before taking the nation’s standardized medical licensure exams, which measure both knowledge and clinical skills. Upon passage, they can register as medical practitioners.

Those who pursue the more elite seven- or eight-year curricula gain additional training and research experience and earn more prestigious degrees (master’s or doctorate respectively), before taking the same licensure exams as their bachelor’s degree-earning colleagues.

Though the varied tracks offer differing levels of rigor in the classroom, Adashi said the consistency of the licensing exam requirements ensures a baseline of training and competency across the profession.

Image: Eli Adashi

“If everybody takes the same licensing examination, I think it really doesn’t matter if you do it in eight years, or seven years or five years,” Adashi said. “If you have an equating national benchmark that allows you to compare students from anywhere in the country then you are in reasonably good shape.”

In addition, China appears to be working toward winnowing the number of different paths into the profession, Adashi said. The seven-year programs have been left out of several recent ministry reports on the future of medical education.

Residency difficulties

Where China’s medical education system urgently needs more development, Adashi said, is in creating residency programs like those pioneered in, and required in, the U.S. Residency, after all, is where newly credentialed doctors grow into truly experienced hospital physicians by way of the structured evaluation and guidance of seasoned supervising doctors.

“It’s essential to the patient to know that the doctors who are training, for instance to do surgical procedures, are carefully supervised, their progression is monitored, they take exams to prove their competence, and they acquire graduated responsibilities as they proceed,” Adashi said.

After many false starts over decades, China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission has recently defined requirements of between one and three years of graduate medical education, depending on undergraduate training and desired specialty. But the standards of evaluation vary widely by region, Adashi and his co-authors wrote. Adashi said they do not yet amount to a rigorous, nationally reliable standard.

“Their residency program is their challenge,” Adashi said. “It is unstructured and non-uniform. It is everything you don’t want it to be.”

China is clearly keen to continue building a robust residency system for its aging population of 1.4 billion, Adashi said.

“They understand the importance,” Adashi said, “but they have barely gotten underway.”