PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In 2011, with an urge to pursue a deeper education in health care, medical research assistant and phlebotomist Akosua Adu-Boahene moved to Rhode Island from Kentucky to earn a master’s degree in public health at Brown University. The move brought the young Ghana native into Providence County’s community of more than 13,000 fellow immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa.

Before enrolling at Brown, Adu-Boahene spent more than two years working at Women & Infants Hospital. Her personal experience as a health care worker and an immigrant, combined with what she often observed among her friends and neighbors at the Empowerment Temple of the International Central Gospel Church in Pawtucket, made it apparent that for many people, the culture shock of moving from West Africa to New England included significant barriers to accessing health care. With the encouragement of her pastor, she decided to help by organizing church health ministry programs such as quarterly health fairs with screenings and educational events. She resolved to start a more permanent clinic in Pawtucket and, as a student at Brown, dedicated her thesis work to conducting a health needs assessment within the community.

A summary of those results appear this month in the Rhode Island Medical Journal. The paper provides a rare quantitative and qualitative assessment of health and health access in a sampling of Rhode Island’s large African immigrant community. That community is a diverse population that often gets errantly lumped together with U.S.-born African Americans, but a common theme in the data is that despite a prevalence of developing chronic health problems, many immigrants don’t seek, and don’t know how to seek, care.

“When we emigrate to the U.S., we have little background knowledge of preventive medicine,” Adu-Boahene said. “But there are real needs. Even if we do seek care, we have limited information on how to access the U.S. health care system.”

Meanwhile, local researchers haven’t known much about the population’s needs, or about the community’s disconnection from care.

“There have been some studies of African immigrant communities in the United States but none in Rhode Island,” said co-author and thesis advisor Bart Laws, research assistant professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown’s School of Public Health. “It was necessary for Akosua to go out and get some primary data.”

Chronic conditions, sporadic care

Adu-Boahene conducted a “mixed-methods” study, meaning that she not only recruited and surveyed 101 immigrants from Ghana, Liberia and Nigeria to amass quantitative data, but also she interviewed a clinical pharmacist, five local physicians and three clergy members who serve the community to gain a deeper, more qualitative understanding than numbers alone can produce.

Adu-Boahene’s sample consisted of a young (75 percent under age 44) and well-educated (83 percent with at least some college) population with a high rate of employment (90 percent). More than half had become either U.S. citizens or permanent residents. Three out of four participants had health insurance.

Even though nearly half reported a chronic health problem, the group was somewhat disconnected from routine care. Among those with insurance, only 69 percent had a blood pressure screening in the past year, 54 percent had a dental exam and 49 percent reported having a cholesterol screening.

The sample revealed a variety of chronic ailments. Topping the list were joint and back pain, high blood pressure, diabetes and being overweight. They also reported high levels of stress.

“The culture shock is huge,” Adu-Boahene said. “It’s fast-paced over here, but we’re so laid back where we come from. And we are very communal — in the U.S., it’s ‘each man for himself.’”

The interviews with doctors and pastors backed up the insight that many immigrants — especially undocumented individuals, who were not well-represented in the sample — don’t seek the preventive care that could prevent or address some chronic ailments.

“Informants also concurred that African immigrants tend to be slow to seek health care and may present with relatively advanced problems,” reported the study, co-authored with Dr. Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie, clinical associate professor of medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School. “This was seen in part as a function of unfamiliarity with preventive care and of concern about cost. However, physicians and clergy also perceived African immigrants as stoical, with a high threshold for pain.”

A common stress for many immigrants is that their education often doesn’t translate to commensurate careers in the United States. The fact that many take jobs with a lot of hard physical work instead helps to explain the prevalence of joint and back pain.

Adu-Boahene said she was surprised by the prevalence of hypertension. One possible explanation could be the stress. Another could be the prevalence of salt in U.S. urban diets, where fast and processed foods are abundant. She was also surprised by anecdotal evidence that the baseline health of refugee immigrant children is good, it sometimes worsens considerably within a year.

“They are worse off than their socioeconomic [counterparts],” she said, referring to people of similar socioeconomic status but who were born in the U.S.

Much of the concern about health needs came not from her fellow immigrants but from the pastors and doctors, she said.

“We’re not too forthcoming about our health problems,” she said. “If someone has cancer, they’re probably not going to make that revelation to you. I got this piece of information from the informants.”

Pursuing a clinic

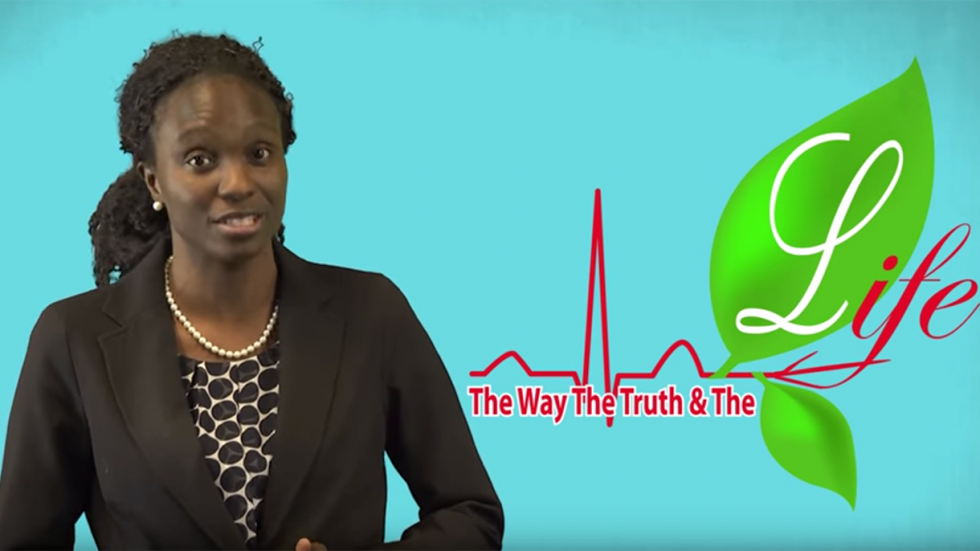

If members of the community aren’t quite rushing to the clinic, then Adu-Boahene hopes to bring it to them. Since graduating from Brown in May 2016, she’s continued to work to realize her vision of establishing the WTL Health Clinic, a free clinic initiative (WTL stands for "The Way, The Truth and The Life"). She’s been talking with potential partners to arrange space, funding and volunteers while also checking off key administrative steps such as incorporating and securing insurance.

Adu-Boahene’s master’s research has helped her focus on the initial suite of services she’d like to offer.

“We’re going to begin by looking at diabetes, hypertension and behavioral health, based on the findings from the health needs assessment” she said. “We will then expand upon our services in the future.

Having documented the needs as a student, Adu-Boahene is now working as a graduate to meet them.