PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Eight will enter, but only three (maybe four) will emerge.

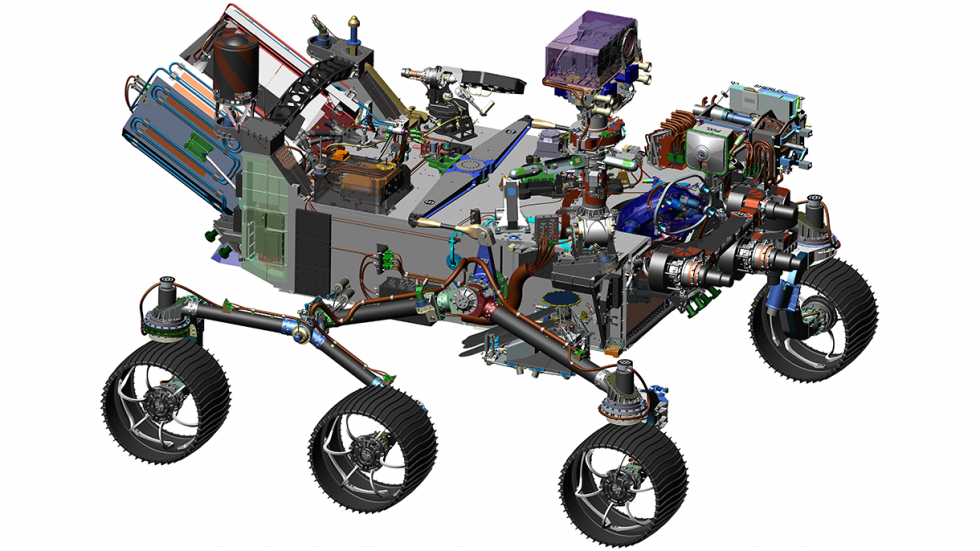

This week, NASA will winnow down the list of potential landing sites for its new Mars rover scheduled for launch in 2020. At a workshop kicking off Wednesday in California, planetary scientists from around the country will gather to hear the scientific merits of the eight potential sites now on NASA’s list. On Friday, the scientists will vote for those they think are best. And based on that vote, NASA will cut the list to “three or four” sites, according the workshop website.

Brown faculty members, as well as current and recent graduate students, have been deeply involved with the Mars 2020 site-selection process from the beginning. Three of the eight sites on the current list of contenders were proposed by Brown researchers, and they’ll be at the workshop to make the case for their sites.

Anyone can follow the proceedings live at https://ac.arc.nasa.gov/mars2020. Presentations begin at 11:30 AM Eastern time on Wednesday. Voting takes place Friday at 1:00 PM. [Editor's note Feb. 10: Two Brown-led candidates, Jezero and NE Syrtis (more information below), came in first and second in Friday's vote.]

The workshop is a little like a “bake off” or the prize pig competition at the county fair, says Jim Head, a professor in Brown’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences who is involved in two of the three Brown sites. “Everyone comes with their favorite science and exploration site and proudly strives to show how it has just what the NASA officials, engineers and the scientific community want,” Head said.

Brown professor Jack Mustard is well acquainted with the kind of site NASA wants for its new rover. He’s a member of the site-selection steering committee for the mission and was chair of the Mars 2020 science definition team, the group that helped set the mission’s science goals.

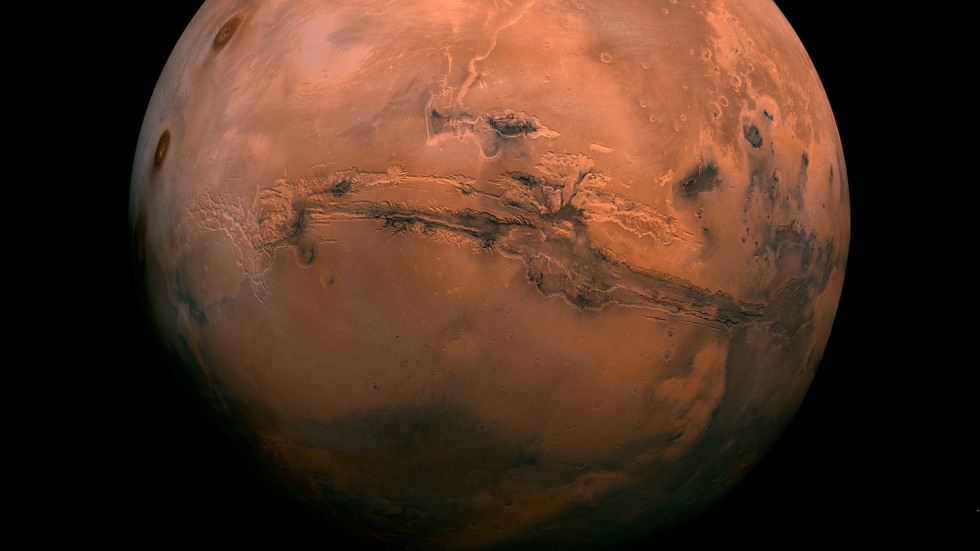

Those goals, Mustard says, include searching for the signs of potential past life on Mars and doing fundamental science aimed at better understanding the history of the Red Planet. A key part of the mission is collecting a set of rock samples and caching them away at the landing site. The plan is for a future mission to collect them and bring them back to Earth for analysis that can’t be done currently with a robotic rover.

The Mars 2020 landing site needs to be the best possible spot on Mars to achieve those objectives.

“We’re looking for a site that’s ancient — around 4 or so billion years old — because that’s when we think Mars had water flowing and a more clement environment,” Mustard said. “We need to be able to characterize the habitability of that environment and look for preserved biosignatures. And in addition to the science on the ground, we need to find the right samples to return later.”

Having survived two previous elimination rounds, the Brown sites have shown that they have right stuff so far. The presenters are hoping to drive the point home at the workshop this week.

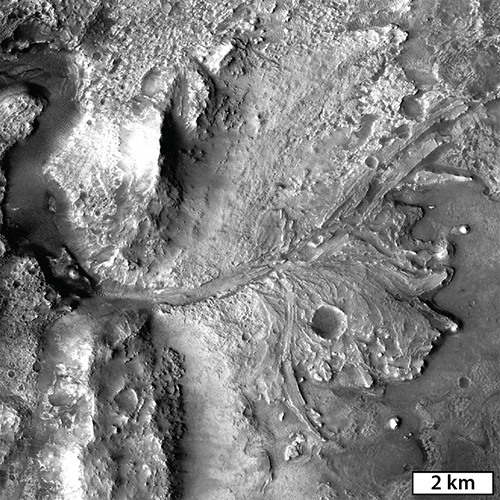

An ancient lake

Tim Goudge, a recently graduated Ph.D. student who worked with Head and Mustard, will make the case for Jezero Crater, a circular gash in the Martian surface about 30 miles across that is believed to have been home to an ancient lake. The site’s key feature is a large delta deposit emplaced where a river once fed the lake. The sediments in that deposit were drawn from a 4,600-square-mile watershed, Goudge says. And that’s part of what makes Jezero such an attractive spot for exploration.

Credit: NASA/MSSS/ASU/GSFC

“Any organic matter that might have been in that [watershed] is going to get concentrated in an area we can explore with a rover,” Goudge said. “That makes it easier to maybe find the needle in the haystack because you’re potentially collecting lots of needles in one spot.”

While the delta is the main attraction at Jezero, it’s not the only one. The floor of the crater is lined by what appears to be a lava flow, which could shed light on the volcanic history of Mars. There are also mineral deposits that could offer clues about what the ancient atmosphere of Mars was like.

“It’s not just a one-trick pony,” Goudge said. “It’s like you get to see the Rolling Stones, the Beatles and The Who — quite a lineup.”

Life underground?

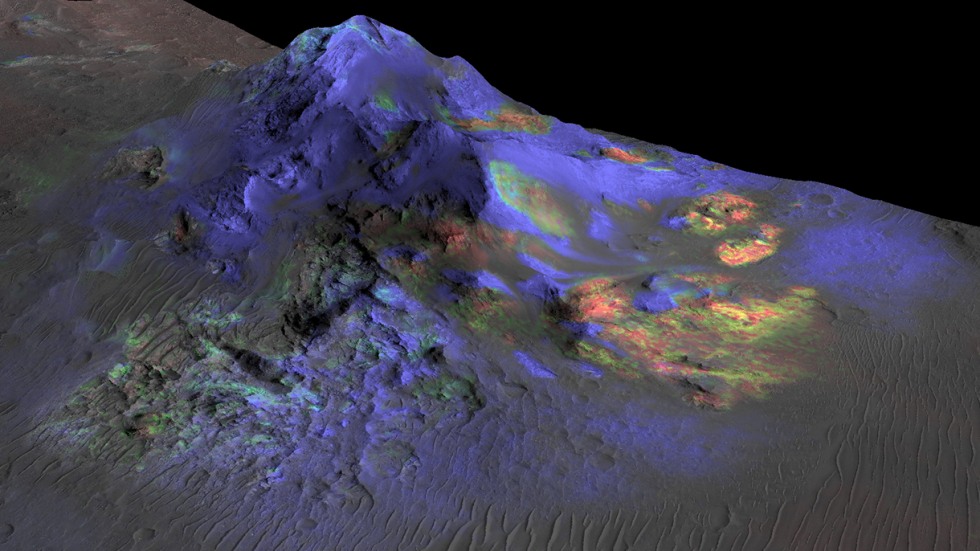

Mustard is leading the charge for a very different kind of site known as Northeast Syrtis Major. Whereas Jezero represents an ancient lake on the Martian surface, NE Syrtis has the remains of a hydrothermal system where water once percolated just beneath the surface. Mustard and many other scientists think spots like this may be the best place to look for signs of ancient Martian life.

And NE Syrtis had a particularly interesting hydrothermal system, Mustard says. Orbital observations have shown patches on the surface where the mineral olivine has been altered by water to form carbonate. That olivine-to-carbonate reaction is known to liberate hydrogen, which could have been an energy source for microbes.

“On Earth we have evidence of these ancient lineages of bacteria that lived off of rocks in the subsurface, feeding off of chemical energy,” Mustard said. “Here we have that feedstock and there was water, so that makes it really exciting.”

And like Jezero, there’s more at NE Syrtis than just one main attraction. Mike Bramble, Mustard’s graduate student who will also be presenting on NE Syrtis at the workshop, says the spot is among the most mineralogically diverse on Mars, with many different kinds of deposits within quick roving distance. The site also allows access to some of the planet's oldest exposed surfaces.

“The rocks we would touch down on would be 4 billion years old, older than any rocks on Earth,” Bramble said. “So that’s a chance to answer all kinds of questions about the formation of Mars and the formation of planetary surfaces in general.”

Two different environments

Brown’s third site is known as the Nili Fossae trough, a groove nearly 20 miles wide that stretches nearly 400 miles across the Martian surface. Kevin Cannon, a Ph.D. student who will make the case for the trough, says the region boasts two different types of habitable environments.

First, Cannon says, there are alluvial fans created when ancient waters washed into the trough. They may represent a habitable sedimentary environment similar to the one at Jezero. But the region is also home to debris blasted out of nearby Hargraves crater, a spot that is thought to have been home to a subsurface hydrothermal system similar to NE Syrtis. Cannon says that debris is a good candidate for having preserved biosignatures from the subsurface.

“That subsurface environment would have been protected from radiation and oxidation when it was in place,” Cannon said. “Then it was excavated much later by this impact and deposited where we would land.”

Plus, Cannon and Mustard discovered recently a number of craters on Mars similar in size to Hargraves that are rich in glass created by crater-forming impacts. Hargraves likely has it too. Impact glass has been shown by Brown geologist Pete Schultz and others to preserve ancient biosignatures from Earth. Perhaps it could do the same on Mars.

And like the other Brown sites, the trough has a wealth of mineralogical features — as well as a huge sheet of volcanic material — which could help scientists piece together the geological history of the planet.

Brown on Mars

While each of Brown’s planetary scientists has their own favorite in the site-selection race, all are hoping that at least one (and hopefully more) Brown site makes the final cut. It certainly wouldn’t be the first time Brown put its stamp on Mars exploration.

In the early 1970s, the late Brown professor Tim Mutch helped select the site for the Viking lander, and was principal investigator for the spacecraft’s camera system. “Since that time, dozens of Brown planetary scientists have contributed to the site-selection process and to the missions once they have successfully landed,” Head said.

Mustard, Head and the rest of the Brown planetary team hope the Mars 2020 rover will be another example.