PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In the 40 years since it prohibited Medicaid funding for abortion, the “Hyde Amendment” has not only persisted but also pervaded an ever-wider policy blueprint for restricting access to pregnancy termination. In an article in JAMA tracing the amendment’s history and impact, two Brown University authors note that the Hyde blueprint now has a renewed chance of becoming codified into law.

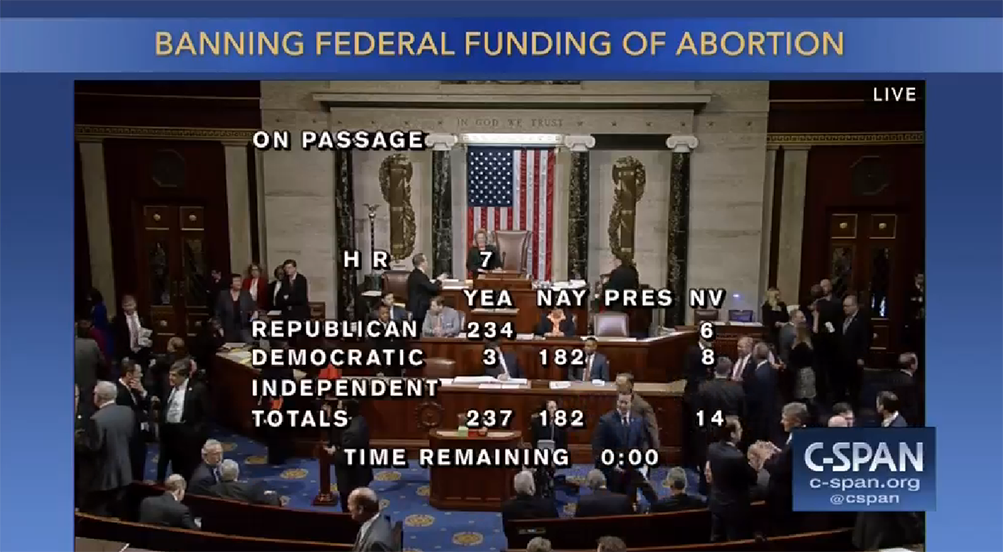

Passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on Jan. 24, the “No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion and Abortion Insurance Full Disclosure Act of 2017,” a bill also known as H.R. 7, would prohibit all federal funds from underwriting abortion or subsidizing insurance that provides coverage for abortion. That would essentially turn the Hyde blueprint of restricting public funds for abortion into permanent law. The bill’s fate in the U.S. Senate, where it likely lacks a filibuster-proof majority, is unclear, but for the first time since it was first introduced in 2011, it has a receptive president in the White House, said essay co-author Dr. Eli Adashi, professor of medicine and former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University.

Under former President Barack Obama, Republicans knew “there was no future for the bill,” Adashi said. “Now there is at least a theoretical possibility that something will happen.”

A history of expansion

The Hyde Amendment was born on Sept. 30, 1976, as a one-sentence rider on an appropriation bill for fiscal 1977, wrote Adashi and Rachel Ochiogrosso, a student at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School. It was specific to Medicaid and allowed an exception in the case of danger to the life of the mother.

After the rider survived a four-year legal battle resolved in its favor by the Supreme Court, the blueprint of prohibiting federal monies from funding abortion continued to expand to new areas of the federal budget. It is now the policy of the Peace Corps, the federal employment health benefits plan, the federal prisons, Medicare, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the city of Washington, D.C.

“It is remarkable,” Adashi said. “You have initially a rider that is fairly circumscribed, and then if you were to use a medical analogy, it metastasized.”

Though most Democrats oppose the Hyde Amendment and all but a handful voted against H.R. 7, it was the passage of the Affordable Care Act — aka “Obamacare” — in 2010 that gave the Hyde blueprint relevance to private insurance, the essay notes. A compromise to ensure the law’s passage extended the funding prohibition to federally subsidized health insurance. Today, 32 states prohibit their funds from going to abortion care.

Throughout its history, Adashi and Ochiogrosso wrote, the original Hyde Amendment has endured under Congressional majorities and presidents of both parties. Yet it has also never been formally made permanent law. Instead it lives on as an annually renewed appropriations rider.

“There’s a lesson here not to dismiss riders in general or to assume they will stay where they are,” Adashi said.

So long as the blueprint persists, in whatever form it does, the net effect of the Hyde Amendment is that abortion remains difficult to attain for low-income women whose insurance or benefits prohibit it, Adashi and Ochiogrosso wrote.