PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Public health research shows that alcohol may be a factor in more than 13 percent of deaths due to infectious diseases, including HIV. Drinking undermines the fight against the virus in two main ways, researchers have found: it makes transmission through risky sex more likely and undermines health by relaxing the rigor with which infected people take virus-suppressing medicine.

Over the last few years, Rebecca Papas — research assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University — has worked with experts in Kenya to bottle up the advance of the country’s HIV epidemic (and related violence) by piloting a culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program to promote alcohol abstinence among HIV-infected residents.

Now, building on the pilot program’s results, a new study led by economist Omar Galárraga, an assistant professor at the Brown University School of Public Health, projects that scaling the program up nationwide would save money by preventing costly new infections and improving productivity among the population.

The key, according to Galárraga, Papas and co-authors of the study published in BMC Health Services Research, is that treatment can be successfully delivered by “paraprofessionals” with limited training, who are in far greater abundance than the nation’s limited number of psychiatrists, estimated to be 75 in 2010. Those with as little as a high school education have been successful trainees in the pilot program.

“In our pilot intervention study, we demonstrated that trained paraprofessional therapists in Kenya were independently rated to be as competent as college-educated U.S. therapists when delivering a standardized CBT intervention to reduce alcohol use,” Papas said. “This new cost-effectiveness study goes a step further by considering the long-term health and economic benefits to rolling out this task-shifting approach to more people.”

The cost to treat 13,440 people over five years would be $554,000, but the benefits of reduced HIV drug costs and improved worker productivity would be valued at $628,000, according to the team’s “base case” projections.

Benefits outweigh costs

In trials of the pilot program involving about 700 HIV-infected Kenyans who receive antiretroviral medications and also drink alcohol, the team showed that trained paraprofessionals can boost alcohol abstinence rates to 69 percent compared with just 38 percent using the prior standard of care. CBT, which can be delivered to groups in weekly sessions with monthly refreshers, helps participants explore their thoughts, actions and feelings in situations where the risk of drinking is acute, so that they can better resist it.

The new study projects the costs of training and then continuously employing enough paraprofessionals to deliver the CBT at 12 sites in five regions around the country. The costs included paraprofessional salaries, travel expenses, housing allowances, and even furniture and equipment.

“The scale-up was developed in consultation with on-the-ground experts who thought carefully in terms of feasibility of the piloted model and how it could be expanded across five regions in Kenya given the infrastructure and knowledge that already exists,” Galárraga said. “It is meant to be a realistic approximation of what can be done if there is the political will to act on this promising and economical intervention.”

Those costs, meanwhile, were tallied alongside the economic benefits that would accrue from the net additional reduction in drinking from CBT over standard care: reduction in new HIV infections, improved health, and therefore improved labor productivity among people who were more consistent in taking their medicine.

“Each new case of HIV averted implies tremendous costs saved because it is an expensive, lifelong treatment,” Galárraga said.

He his co-authors drew on numerous research sources to provide an evidence base for their projections. These included rates for how often alcohol abstinence translates to reduced HIV transmission and comparisons of the rate at which HIV-infected people who drink adhere to their medication vs. HIV-infected people who don’t drink.

A key assumption in the model was that the effect of the CBT — alcohol abstinence — would last for at least two years. To ensure they explored the implications of being wrong, the team also crunched the numbers for durations of one, five and 10 years. In the study, the authors acknowledge that the net savings disappears if CBT’s effects last for only a year, but they also increase considerably if people stay abstinent from drinking longer. Similarly, the researchers varied other key parameters to understand how sensitive their projections were to different assumptions.

“The sensitivity analyses show that under most assumptions the benefits are still greater than the costs, meaning that the intervention makes sense not only in terms of health impact but also in monetary terms,” Galárraga said.

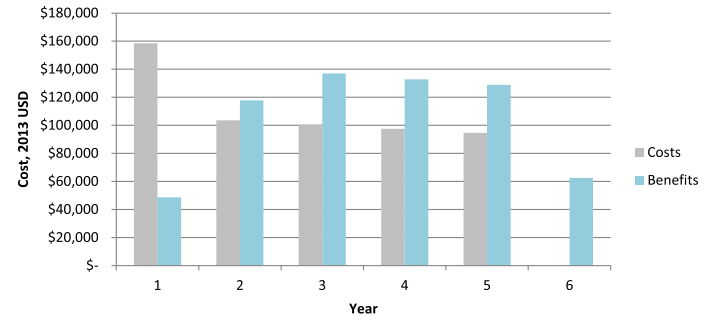

With the upfront costs of all the training, the benefits don’t begin to exceed the costs until the second year of the program, they project, but from year two on, the program recoups more economic value than it costs until the total benefits overtake the expenditure, yielding savings.

Global relevance

The authors argue that not only should the program expand in Kenya, but that other countries with HIV and alcohol use problems should also consider the intervention, which is now being further tested in a larger efficacy trials.

Galárraga said the study demonstrates the potential contribution that mental health treatment can play in fighting infectious disease.

“Budgets are being cut everywhere and many public health interventions, including mental health, are being relegated and even abandoned,” he said. “Showing that there is a high impact not only in health terms but also in monetary benefits may help in funding allocation discussions.”

He added that Americans benefit when researchers work with colleagues overseas to address problems like epidemics. As HIV, Zika and Ebola all illustrate, infectious diseases don’t stop at borders. Addressing misery and economic deprivation, both consequences of health crises, can also reduce the appeal of extremism, he said. It is a positive application of “soft power” for the United States, he added, to lead by helping to spread global health benefits.

“We live in a globalized world with global threats,” he said. “Higher HIV rates in sub-Saharan Africa present a destabilizing and threatening environment not only locally but also abroad.”

In addition to Galárraga and Papas, the paper’s other authors are Burke Gao, Benson Gakinya, Debra Klein, Richard Wamai and John Sidle.

The National Institutes of Health funded the intervention study.