PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — On a research dive in 2011 off the Aegean Sea coast of the fishing village Çeşmealtı, Turkey, a lucky pair of graduate students bore accidental witness to a phenomenon scientists have otherwise only ever seen in the lab: the theater and violence of male cuttlefish competing for a mate.

Equipped with video cameras to record data for a study of camouflage, the team captured the combat, analyzed it and have now published the results in the American Naturalist to share the science and the spectacle with the world.

“This male just kind of appeared right next to my left side and rested next to a clump of algae on the sea floor,” recalled Justine Allen, who went on to earn her Ph.D. in neuroscience at Brown and is now an adjunct instructor in the University’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “The female was a few meters in front. Out of nowhere he just swam up, grabbed her, and they mated in the head-to-head position.”

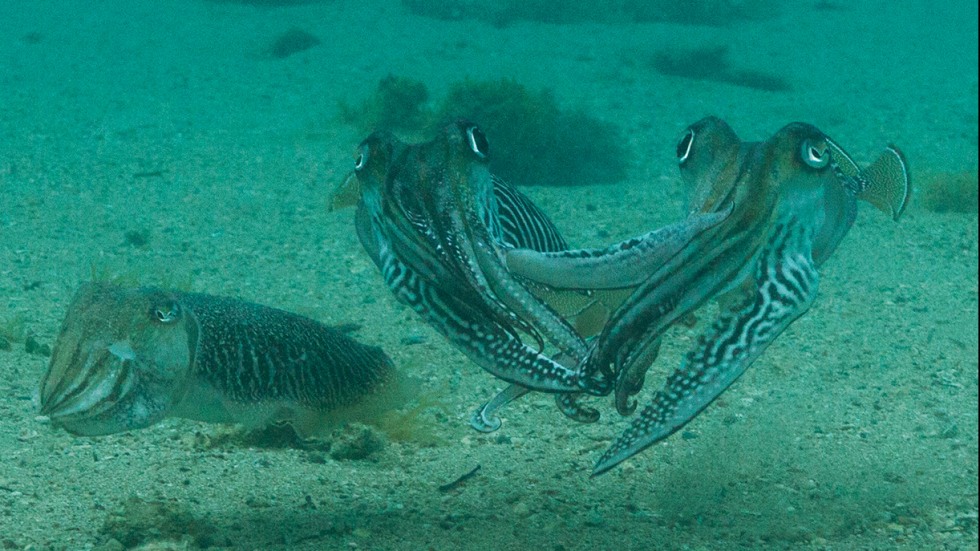

The video she shot with co-author Derya Akkaynak, now at the University of Haifa in Israel, shows a dramatic sequence of events. The female and her newfound male consort finished mating and started to swim off together — a male common European cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis, will “guard” his mate to make it more likely that it’s his sperm that she’ll use to fertilize her eggs when she lays them.

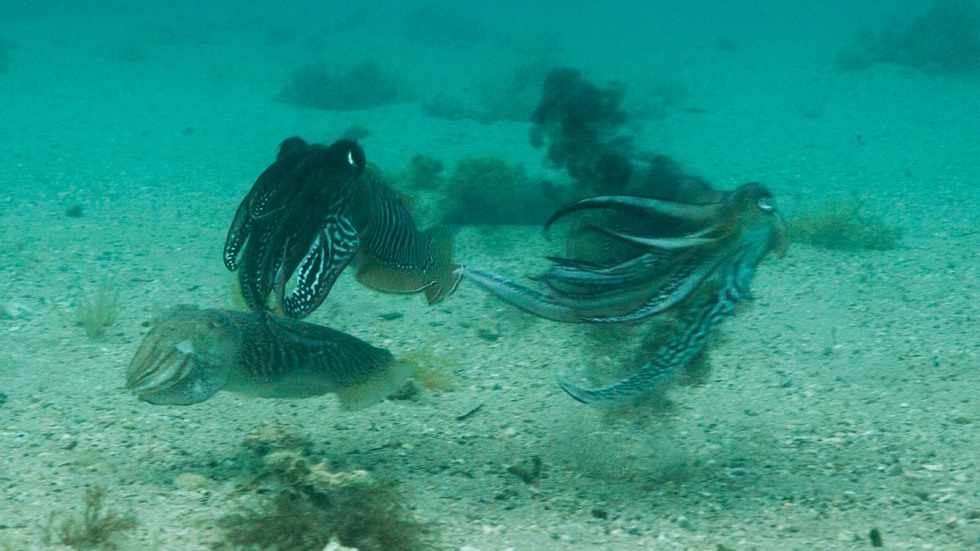

But a little more than three minutes later, a second male disrupted the new couple’s harmony. To announce his intrusive intentions, he brandished two of the many peculiar gestures cuttlefish employ to show aggression: He extended his fourth arm toward the consort male and dilated the pupil of the eye that faced his foe.

“They have a whole repertoire of behaviors that they use to signal to each other, and we’re just barely starting to understand some of them,” said Allen, who is also the training grant manager in Brown’s Office of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies. “A lot of their fighting is done through visual signals. Most of these battles are actually these beautiful, stunning skin displays. It’s a vicious war of colors.”

But sometimes, as the study documents, they’ll attack physically.

In the paper, the authors analyze the emergence and progression of these behaviors, recorded for the first time ever in the wild, in the context of game theory. Scientists since Aristotle have been curious about the courtship and sexual selection behaviors of cuttlefish. In any species, Allen points out, the way mating takes place has everything to do with their survival as a species.

The height of those stakes are why things then proceeded to get nasty.

Three escalating bouts

The intruder’s pupil dilation and arm extension began the first of three brief bouts over the course of about four minutes, each with escalating levels of aggression. The consort male met the initial insult with his own arm extension and — as only color-changing animals like cuttlefish can do — a darkening of his face. Then both males flashed brightly contrasting zebra-like bands on their skin, heightening the war of displays further.

Bout number one would go to the intruder as the consort became alarmed, darkened his whole body, squirted a cloud of ink in the intruder's face and jetted away.

For more than a minute, the intruder male tried to guard and cozy up to the female, but the consort male returned to try to reclaim his position with a newly darkened face and zebra banding. He inked and jetted around the pair to find an angle to intervene, but the intruder fended him off with more aggressive gestures including swiping at him with that fourth arm. Bout number two again went to the intruder.

Then the intruder crossed a line.

He grabbed the female and tried to position her body to engage in head-to-head mating, but she didn't exhibit much interest, Allen said.

The intruder’s act brought the consort male charging back into the fray with the greatest aggression yet. He grabbed the intruder and twisted him around in a barrel roll three times, the most aggressive gesture in the cuttlefish arsenal. He also bit the other male. The female, meanwhile, swam out of the fracas.

The intruder fled, chased off by the victorious consort male. Study co-author Roger Hanlon, Brown University professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and senior scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., moments later observed and filmed the consort swimming with the female. Allen was affiliated with the Brown-MBL Joint Program in Biological and Environmental Sciences while Akkaynak was studying in a joint Massachusetts Institute of Technology-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute graduate program.

“Male 1 wins the whole thing because we saw him with the female later, and that’s really what matters,” Allen said. “It’s who ends up with her in the end.”

Fight analysis

Though more violent than most of the interactions scientists have documented in lab tanks, the field observation appears to back up the scientific community’s working hypothesis of male cuttlefish rivalry: It suggests a “mutual assessment” model of game theory in which the combatants base their actions on how they judge their ability to prevail relative to their opponent’s ability. That model predicts, for example, that the cuttlefish will escalate the fight at the same rate, as if to feel each other out. It also predicts that the fight will end when one has gained a clear upper hand over the other. Both of these predictions appeared to play out in the three escalating bouts and their conclusion.

The alternative models, where the combatants don’t factor in their opponent’s strength, make different predictions that were not as evident in the way this particular fight proceeded. Study co-author Alexandra Schnell of Normandie University in France led this analysis.

Of course, exciting as it was, the episode amounts to only one observation, Allen acknowledged. Many more observations and carefully designed experiments are needed to truly understand cuttlefish reproductive behavior. That speaks to the value of getting out of the lab and away from the computer.

“A lot of science, especially animal behavior, needs to be done outside, in the field, with wild animals,” Allen said. “You have to be lucky enough to catch them on film to analyze what they are doing, but science is happening outside all around us, all the time.”