PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In 1916, when Anna Hass Morgan was a student at the Women's College in Brown University, her English professor told her that Eugene Debs would be speaking in Providence. Her professor had read Morgan’s politically themed essays and thought she might be interested in hearing the socialist candidate for U.S. president speak.

Morgan, who lived in nearby Rehoboth, Massachusetts, and commuted to Brown, decided to attend — even though she knew her mother wouldn’t approve. When she arrived, she was surprised to see her father there, too.

“I went up to my father and I said, ‘Hello… I told Ma I went to a movie.’ And he looked very embarrassed, and he said, ‘I told your mother I was working overtime.’”

In the subsequent years, Morgan became a political activist, raising money to buy ambulances for the rebels during the Spanish Civil War and organizing laborers for the Workers Alliance during the Great Depression. She was an early supporter of civil rights and protested the Vietnam War. She became involved with the Communist Party, and in 1952, because of her open support for leftist causes, she was called before the Ohio Un-American Activities Committee. She refused to testify and was charged with contempt. Morgan’s first husband left her because of her politics.

“He told me that I could choose him or the Communist Party,” she said. “I chose the Communist Party.”

Morgan’s story, peppered with anecdotes like these, is housed in the Brown Women Speak oral history collection, part of the Christine Dunlap Farnham Archive on the history of women at Brown University. It comprises nearly 200 oral interviews of Pembroke/Brown alumnae who graduated between 1911 and 1993. During that time, the Women's College in Brown University was renamed Pembroke College in Brown University in 1928 and eventually merged with the men's college in 1971. The stories they tell offer an intimate peek into what life was like for women at Brown over the course of those 82 years — they also shed light on the many paths they took after graduation.

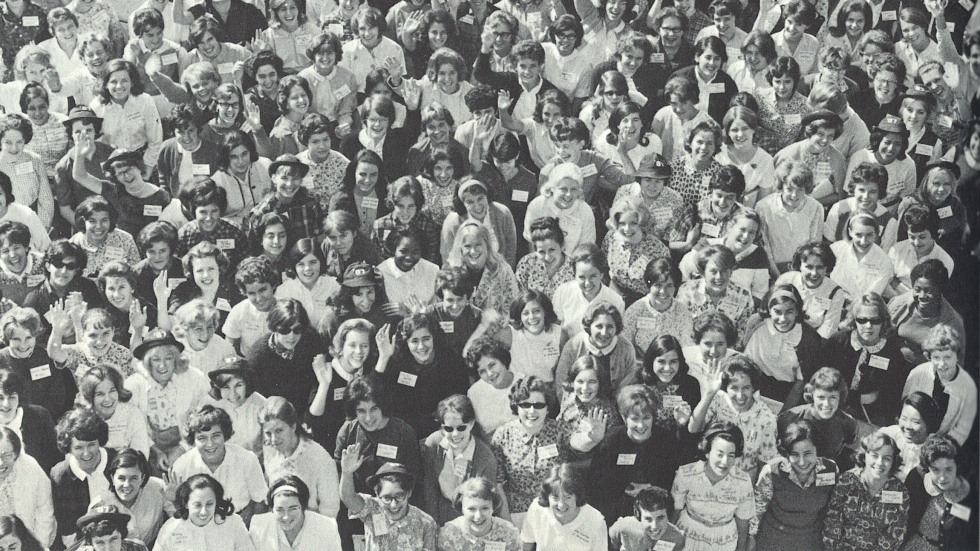

This year, as Brown celebrates the 125th anniversary of women first enrolling at the University — a major conference begins on Friday, May 5, bringing more than 700 alumnae and prominent guest speakers to campus — the Brown Women Speak collection is marking its own 35th anniversary.

Initiated in 1982 by the Pembroke Center Associates — a group of alumnae, parents and friends who support the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women — and Pembroke Center founding director Joan Scott, the oral history project was created to document the daily experiences of the women who went to Pembroke and Brown and the effect those experiences had on their lives.

The personal conversations and moments captured in these stories, like those of Morgan’s, make them an integral part of the historical record, says Mary Murphy, the Nancy L. Buc ’65, ’94 LLD hon. Pembroke Center Archivist.

“Oral histories give you the close read of history as opposed to a historical text that gives you a more distanced read,” Murphy said. “Some of the things that women bring up in these interviews, they can be such tiny details of the conversation or something they say in passing. But in aggregate, when 20 or 30 women mention one thing in passing, you begin to see this picture emerge about events or people that might have been missed in the official history.”

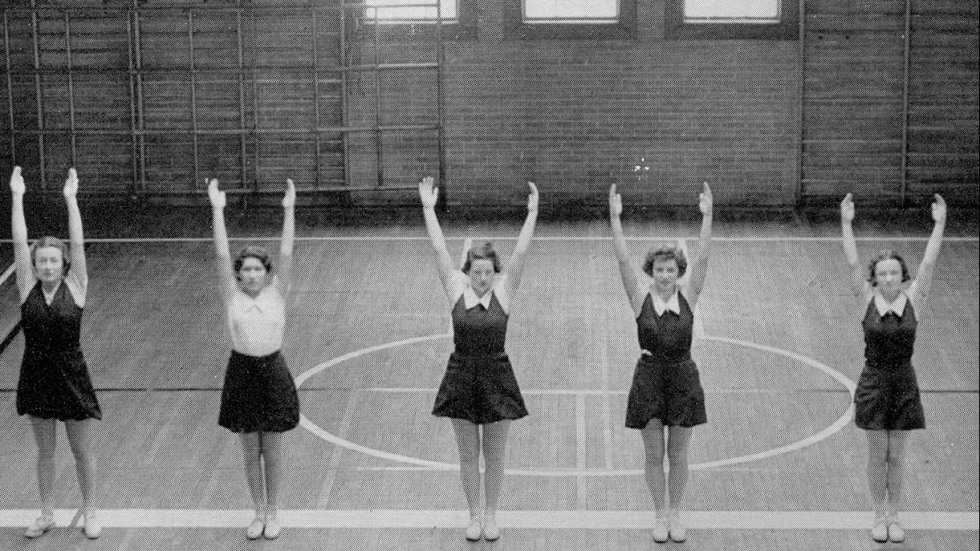

Several examples in the archive illustrate this point, Murphy says: memories of the “parietal rules” that strictly governed the behavior of Pembroke women in ways far different than those governing Brown men; mentions of Arlene Gorton, the beloved Pembroke College director of physical education and athletics from 1961 to 1971, who later became the assistant athletic director when Pembroke and Brown merged; and references across the decades about struggles to access birth control and reproductive health care.

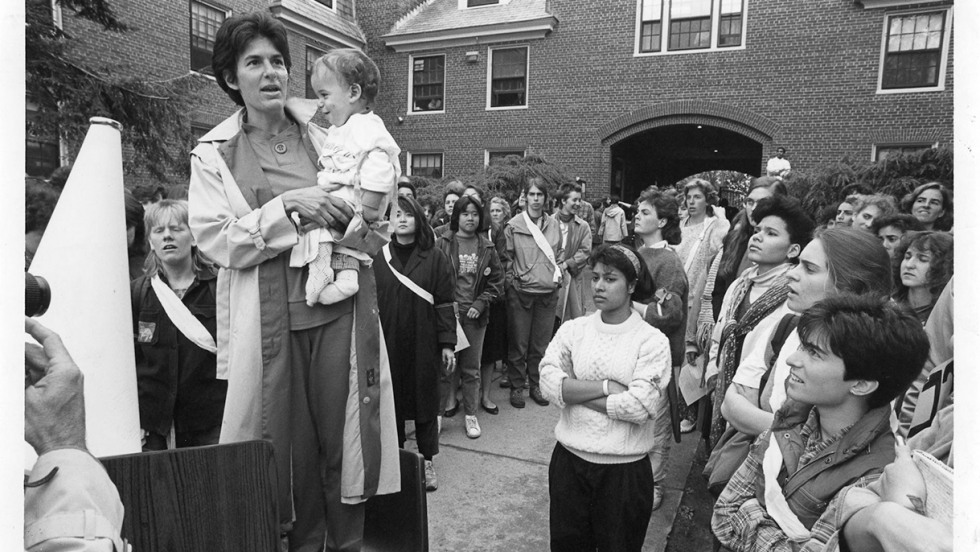

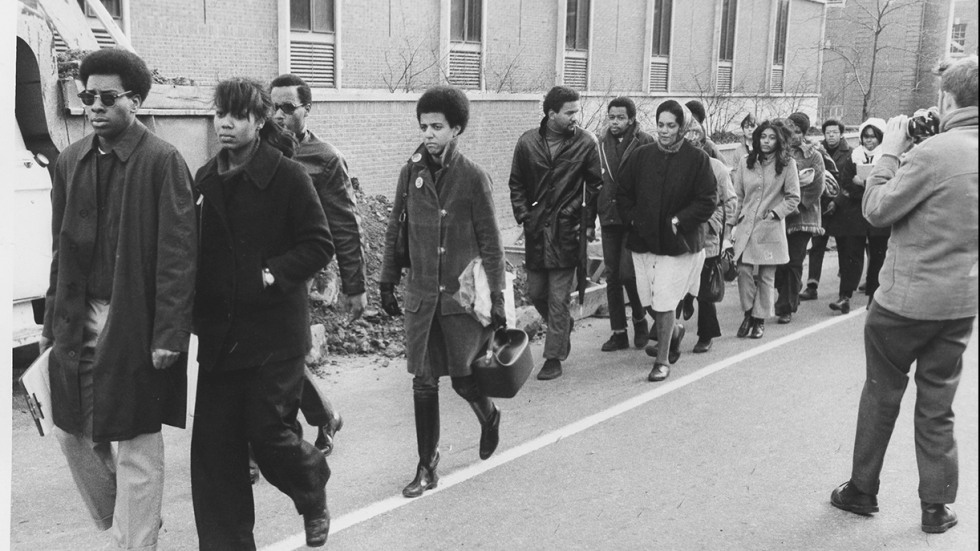

The archive additionally details major historical events, both on campus and off, including the Depression, both world wars, the merger of Brown and Pembroke, and campus activism and protest in the 1960 and ’70s.

But the histories are also filled with happy recollections of day-to-day life at Brown: parties, friendships, theater productions, classes, professors and careers that are clearly cherished memories.

“There’s a great joy in a lot of the interviews, too, a deep devotion to Pembroke and Brown,” Murphy said. “These interviews are really heartfelt, and that’s also just something you can’t get from a book.”

In 2012, the Pembroke Center launched an ambitious effort to digitize the entire collection and make it publicly accessible. This spring, the project was completed. Nearly all of the recorded histories are available online, each accompanied by a full transcript and a photo of the alumna interviewed. Each history is tagged with the topics covered within it to make searching for specific themes easier.

Throughout the years, alumnae have contributed to the archive, serving as both interviewees and interviewers. Mimi Pichey, a founding member of the feminist activist group Women of Brown United and a 1971 graduate, has been involved since the archive’s formation. In her oral history, she describes the campus atmosphere of gendered social rules and the struggle for equal representation after the Pembroke-Brown merger, as well as the broader political environment of student activism during the Vietnam War and civil rights movement.

Over the years, Pichey has also interviewed a broad range of alumnae, including a psychologist, a romance author, a union organizer, a rabbi, a dramaturge and a teacher. As a longtime feminist activist, Pichey says that Brown Women Speak has provided her with important perspective.

“Despite the fact that progress has been slower than many of us would have liked, when you listen to the archives you see how women today do have many more opportunities than they did in the past,” she said. “For Brown, I think the archives are important for understanding the institution itself and how it’s grown and developed… It helps you understand how institutional and personal decisions that are made today could possibly impact the people of the future.”

Murphy, the archivist, hopes that now that the archive is more accessible, it will begin to serve as a valuable resource for scholars, both within the academy and the community. One downside to having the archive publicly accessible online, she says, is that there is no way to tell exactly who is using it. But the demand is there. This past April, the archive received more than 2,500 unique views, a good monthly result, Murphy says, for a project that is 35 years old and with such a specific niche.

Last year, the Hearthside House Museum in Lincoln, Rhode Island, used the archive for a multimedia exhibit on Rhode Island in the 1920s, and both Loyola University and the Library of Congress have contacted University archivists looking for advice on best practices for this kind of long-term oral history archive.

More recently, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, who graduated in 1967, asked for examples from the archive that illustrated women’s economic experience over time, stories she may call upon in her keynote speech at this weekend’s 125 Years of Women at Brown Conference.

Murphy says that part of the archive’s value, besides its accessibility, is that it provides a window not just into the history of women at Brown, but — in its breadth and depth — into the history of women in the United States more broadly. She also sees it as an important resource for current Brown students both as a tool for conducting primary research and as a way to deepen their own understanding of women’s, and Brown’s, history.

Brown junior Isabel Martin began work on the Brown Women Speak project as a sophomore, editing and reviewing transcriptions of individual oral histories. Recently, she used four oral interviews, including Pichey’s, for a paper she wrote that touched on the Pembroke-Brown merger. Martin, who is concentrating in comparative literature and gender and sexuality studies, says that working with the archive has been a formative part of her time at Brown.

“As Brown students, and as people who identify as women on campus, we have a whole legacy of alumnae who have come before us and changed the institution of Brown and changed the world with their voices and their scholarship,” Martin said. “It is a very empowering thing to have so many voices and experiences and lives that really do support you and your education and your passions and have even made them possible. The archives are a way of connecting with history and your scholarship and a world around you that just stretches everything out and expands your perspective in a really powerful way.”

The archive project is not finished. It might never be. Thanks to the ongoing support and dedication of Pembroke alumnae, Murphy says, she expects to continually add at least five interviews each year, focusing on alumnae of color and more recent graduates to expand the diversity of voices represented in the archive.

“This is the priority right now,” Murphy said. “In order to get the entire story of American history, you need to collect everyone’s history.”

This essential need of today fits in with what has always been the archive’s goal, Murphy says: to give a more complete picture of history by offering generations of University alumnae the chance to reflect on their lives in a way that emphasizes their story as a whole person, not just as a woman or a mother or a wife.

There’s a bittersweet glimpse of this in Morgan’s oral history. Right before the tape of her 1987 interview ends, Morgan — 92 at the time — offers one last thought to interviewer Joyce Tavon (Class of 1984):

“I had it in my mind that, to be honest, I’ll tell you who I am and what I’ve done. And that’s my own life… it doesn’t involve my children and my grandchildren. They all think, everybody thinks… I’m just the great-grandmother. Who agitated in [her] spare time.”