PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] —On a cold, blustery December afternoon, Brown University graduate student Yiyu Xing arrived at the Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) headquarters on Providence’s Capitol Hill and headed to the fourth floor for a warm welcome from Stephen Morris, acting co-director of RIDOH’s Academic Center.

Xing was the department’s first public health scholar, a position newly created in the Academic Center for students to gain experience and credit while tackling questions that are not only “real-world” but also of intense, current interest to the agency.

A master of public policy student at Brown’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Xing brought a background in economics and data analysis. After that first meeting, Morris and his colleagues realized that she’d be well-suited to take on the question of what happens to health care and costs when hospitals merge or otherwise change ownership.

At the time, it was a pertinent, front-burner question as the state’s second largest health system, Care New England, explored a possible sale; by the semester’s end, the issue was red hot with the system’s April 19 announcement of its intent to merge three of its hospitals into the Partners HealthCare system and sell a fourth to Prime Healthcare.

“We’re always looking at outcomes as far as health goes, but what are the outcomes in terms of the economics involved in hospital conversions?” asked Morris, who is also RIDOH’s deputy chief legal counsel. “The one that’s promoted all the time is that you’ll get better results and it will be more efficient. But we don’t have any data to show that. The director of health specifically asked whether or not we could have a scholar to work on that.”

As that project launched, Brown students were already working closely with the department in other capacities. A formal affiliation signed last year with the Brown University School of Public Health includes specific provisions for students to work closely with RIDOH staff. While Xing was hard at work on hospital conversions, nine students in a Brown biostatistics class collaborated with health officials to advance analysis of the department’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) dataset.

“Our longstanding relationship with RIDOH is highly valued for the opportunities it gives our students and faculty to participate in the department's important work,” said Terrie Fox Wetle, dean of the School of Public Health. “The recent formalization of our partnership with the Academic Center provides more and richer opportunities for our students to learn public health by doing public health, and for faculty and students to provide service to the department in our shared mission of protecting and improving population health.”

‘Mutually beneficial’

When Morris reached out to the Taubman Center to alert them to the new public health scholar opportunity, Xing and her advisor William Allen, an adjunct lecturer, answered the call. It seemed a great opportunity to fulfill her capstone project within the public policy master’s degree curriculum, in which students serve in policy-related organizations.

James Rajotte, chief health program evaluator and state innovation model (SIM) liaison, who supervised Xing’s work, said Xing “provided a perfect match for the hospital conversion project as RIDOH’s Academic Center piloted the official public health scholars program.”

“This seemed to be a project that would be mutually beneficial,” he said. “It was something that was on my program’s radar within SIM and had come up with the director at the same time we had started thinking about what project Xing could work on, based on her experience. The stars aligned in that way.”

Xing, who graduated from Brown in May and next heads to doctoral studies at the University of Virginia, said the experience has been uniquely valuable. She had prior internships in the Chinese government, an investment bank and the United Nations. But this was an opportunity to engage in an original inquiry.

“My previous experience told me that a regular internship only means that you maintain an existing framework,” Xing said. ‘What you do is try to follow their guidelines. But here is totally different. It’s innovation. This is more like research.”

Much of Xing’s work has been to learn the best analytical methods to answer the question of what effect hospital conversions have had, if any, on Rhode Island’s health care marketplace. An important component was a thorough search of the health policy and economics research literature. That’s something that RIDOH hadn’t done for about eight years, said Michael Dexter, chief for the Center for Health Systems Policy and Regulation, who sponsored the project.

Meanwhile, Xing also sought out historical data for analysis. The state’s hospital marketplace has produced many examples over the last 20 years. There was Rhode Island Hospital’s integration with the Miriam Hospital to form Lifespan in 1994, the subsequent inclusion of the Bradley Hospital into Lifespan in 1996 and three more moves in 2013: Prime’s acquisition of Landmark Hospital in Woonsocket, Care New England’s acquisition of Memorial Hospital in Pawtucket and Lawrence & Memorial Healthcare’s purchase of Westerly Hospital. In 2016, Yale New Haven Health System acquired Westerly Hospital through its acquisition of Lawrence & Memorial.

Xing said she enjoyed working with people all around RIDOH as she searched for pertinent data. But in her work, she identified a fundamental data gap. The state gathers copious data at the level of individual patients but does not track enough data at the hospital level. The latter source, Xing said, is vital for getting to the heart of how conversions affect hospital costs. One of her recommendations is that RIDOH expand efforts to gather additional hospital-level data, including health care financials.

Despite the data gap, Xing was able to make some initial findings in her analysis. Her analysis suggests there may be a significant increase in prices after hospital mergers and acquisitions. RIDOH officials are now reviewing those results.

Even just the literature search and the identification and recommendations related to the data gap have been important contributions, Dexter and Rajotte said.

Xing said the project was a great model for what she wants to do more of in her career.

“I really regard this as a great experience and inspiration,” she said.

Risky pregnancies

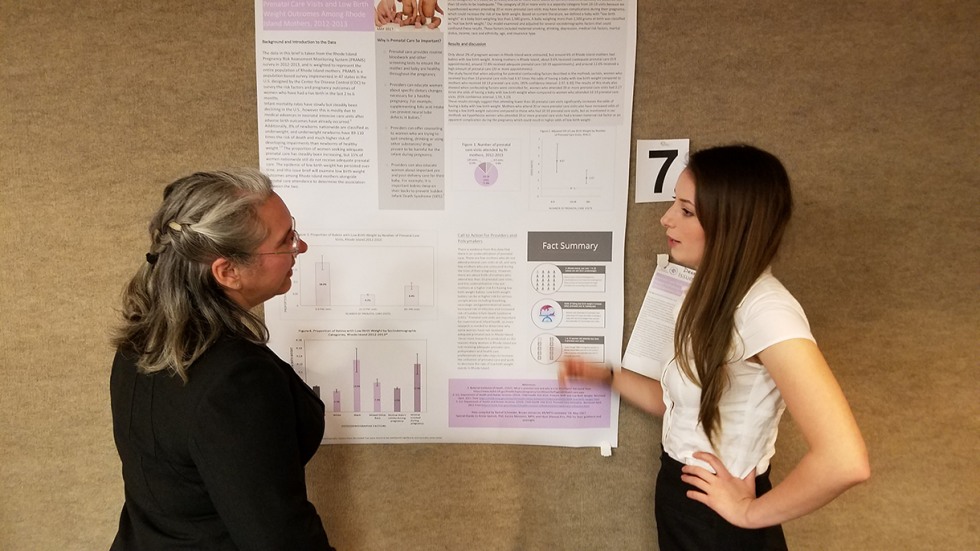

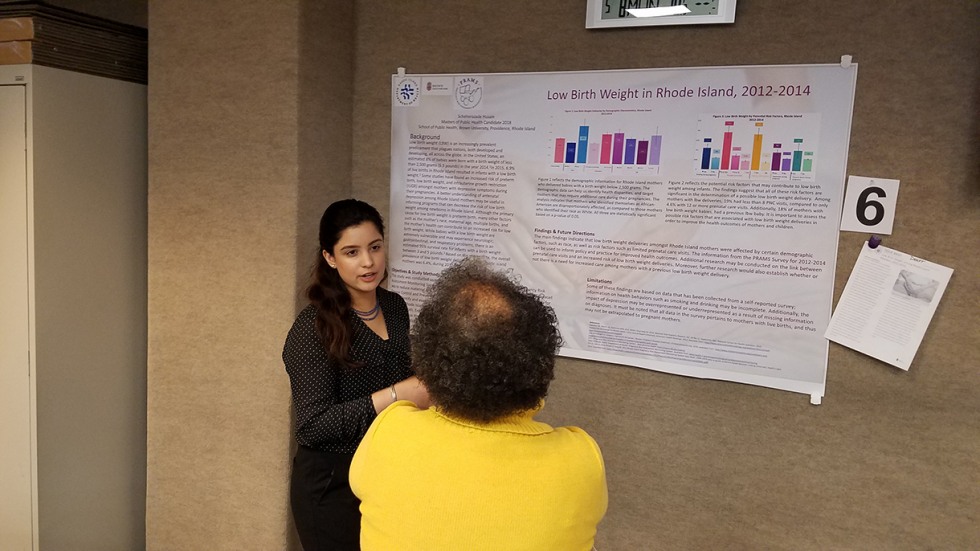

Similarly, members of the class that pored over PRAMS data said they, too, found the experience rewarding. They were looking for new insights to help improve maternal and perinatal care across Rhode Island. At a poster session at RIDOH on May 8, students presented their work including draft issue briefs that department officials can develop further to inform policy.

For more than a decade, Dr. Hanna Kim, RIDOH’s senior public health epidemiologist and an assistant professor of the practice of epidemiology, had been involved in the two-semester class Biostatistics and Data Analysis I & II — but this year, for the first time, Kim and Annie Gjelsvik, assistant professor of epidemiology, challenged students to work with RIDOH’s own data.

“The feedback I’ve had from students is that it was very compelling for them to be working on current strategic objectives from the Department of Health,” Gjelsvik said.

The students’ work provided RIDOH with analyses of several perinatal concerns, including low birth weight, the effects of stress on breastfeeding, how insurance affects access to prenatal care, and postpartum contraception. For example, students helped to identify key risk factors that may contribute to mothers bearing children under 5.5 pounds, said Karine Monteiro, PRAMS coordinator.

Before the class’s involvement, RIDOH’s PRAMS team might have produced two issue briefs a year, Kim said, but now they can do significantly more with the head start the students have produced.

Rachel Schneider, a junior from Wayland, Mass., who will continue in Brown’s master of public health (MPH) program, looked into who is at risk for low birth weight. She found a particularly strong correlation with the number of prenatal visits. Having fewer than 10 was associated with four times the odds of low birth weight as having 10 to 19 visits, controlling for race, income, insurance access, smoking, drinking and other factors, Schneider said. About 10 percent of Rhode Island mothers fell into this risk group with less than 10 visits.

Schneider said she valued the chance to work with RIDOH staff who are trying to address real health problems in the surrounding community.

“There is a lot of collaboration between the School of Public Health and the Department of Health in general, but this project was a really tangible way to work with people in the department,” she said. “We were working with people who knew the surveys really well and knew the dataset really well. All of our mentors were really great.”

Scheherazade Husain, an MPH student from Islamabad, Pakistan, found significant patterns in the data on prenatal visits as well as associations with race (black mothers are at higher risk), a prior history of low birth weight delivery and exposure to domestic violence.

Like Schiender, Husain said it was particularly helpful to work with people who were professionally engaged with the data.

The affiliation between Brown and RIDOH, and other affiliations between the department and local universities, will likely drive more such engagements, said Laurie Leonard, the Academic Center’s new director.

“As we collaborate, we are purposefully partnering in a way that benefits both the academic institutions and the Department of Health so that we are accomplishing necessary goals and providing public health scholars with real-world experience they might not receive through internships at other agencies,” Leonard said.

Indeed, RIDOH officials said, they are gathering more projects for future students to continue what has quickly become a mutually beneficial collaboration.