PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — New research on a crucial protein in fruit flies provides a clear model for a fundamental question in biology that’s significant for drug development in particular: What influences the exact same protein to coordinate a vital molecular process on one chromosome but an entirely different one on another chromosome?

The new study concerns the recently discovered protein CLAMP. Previously, scientists at Brown University had identified CLAMP as the linchpin in the process by which cells in males doubly express their single X chromosome to achieve genetic parity with females, a process necessary for male existence and survival. Now, in a study published in the journal Genes and Development, the researchers have identified another role for CLAMP that is equally essential to males and females alike — the protein is responsible for coordinating the process by which the DNA in newly replicating cells of an embryo becomes properly wound up and structured.

“It’s really exciting because now we have these two separate chromosomes on which CLAMP does vital jobs,” said senior author Erica Larschan. “That sets us up for a compare-and-contrast strategy where we can understand how one protein can function differently in context-specific ways.”

That matters, added co-lead author Leila Rieder, a postdoctoral researcher at Brown, because in order for clinical interventions that target key proteins to do more good than harm, they need to be tailored to a specific context. It may be tempting to block or amplify a gene or protein to treat a disease, but without confining the intervention to that one process, it could upset the entirely healthy actions of the same gene or protein in an unrelated process. That could produce potentially devastating side effects.

“One of the biggest fears about using genetics in people is that there are off-target effects,” Rieder said. “You don’t know when you manipulate a gene if it’s going to have a single effect or if it’s going to have many effects. We don’t understand all the roles that that one manipulation is going to have.”

The confirmation of a second life-giving role for CLAMP, Rieder and Larschan said, provides a perfect example of a protein that is essential in two completely different ways in the convenient research model of the fruit fly.

CLAMP goes GAGA

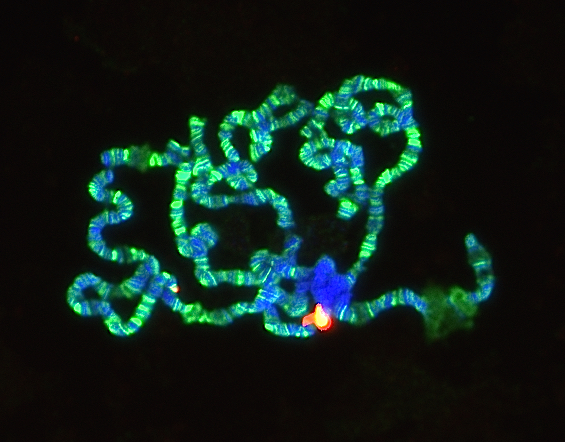

CLAMP binds to DNA all over the fly genome, but it kicks into consequential action when it finds a long series of repeats of the nucleotides GA. In the new study, the scientists found long GA repeats and CLAMP on chromosome 2L at the “histone locus,” where a cluster of genes produce the proteins around which DNA gets wound up to fit inside the nucleus. In many organisms, humans included, cells assemble the same cadre of proteins around which they wrap their DNA. Approximately a yard of DNA is present in every microscopic cell, so it is essential that it be tightly packed but still accessible for regulation immediately in a newly fertilized egg.

In a series of experiments, a team at Brown, the University of North Carolina and Massachusetts General Hospital found that in fruit flies, CLAMP is the protein that launches the process of gene regulation that produces histones by recruiting other known regulators. It is among the very first proteins on the scene of the histone locus in a newly fertilized egg and opens up the histone locus for expression by the cell, they found. Experiments in which the team interfered with CLAMP led almost universally to fly eggs failing to hatch.

Foiling CLAMP proved to be so lethal, in fact, that studying its function at all required an experimental ploy that would allow the scientists to manipulate CLAMP while keeping the flies alive. To understand, for example, how CLAMP lures the other histone-related proteins to the histone locus, the Brown team worked with the University of North Carolina collaborators, including co-lead author Kaitlin Koreski, to generate CLAMP mimics that wouldn’t interfere with natural CLAMP’s DNA binding, but could still attract the other key regulatory proteins that control histone gene regulation.

Same protein, different functions

Larschan and Rieder’s new understanding of CLAMP’s function at the histone locus now matches their understanding of its function on the X chromosome. But they said they don’t yet know exactly what differs about the context of those two chromosomes such that CLAMP, with the same molecular anatomy and bound to the same GA repeats, manages to recruit two completely different groups of proteins to perform separate gene expression tasks.

That’s the next step in their research.

“It sets up a paradigm for the future,” Larschan said. “There are very few cases — that’s what I’m always surprised about when I read the literature — where there are such specific roles at different sites for a single protein. It’s a really strong model.”

In addition to Rieder, Koreski and Larschan, the paper’s other authors are Kara Boltz, Guray Kuzu, Jennifer Urban (a Brown Graduate School alumna), Sarah Bowman, Anna Zeidman (a Brown alumna), William Jordan III (a Brown graduate student), Michael Tolstorukov, William Marzluff and Robert Duronio.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society and the Pew Biomedical Scholars Program supported the research.