PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — As public health officials worry that the increase of opioid use among young adults has helped to spread the hepatitis C virus to a new generation, a study in Rhode Island finds that while screening is common, the follow-up measures needed to stop the spread of the virus are significantly less so.

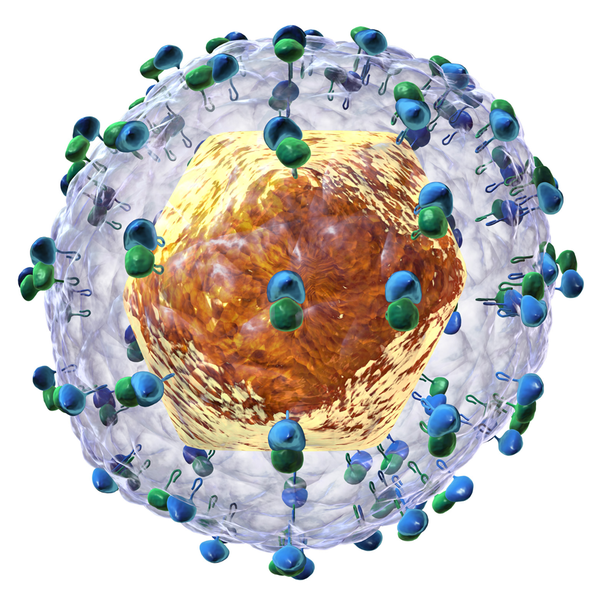

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) can linger for decades before causing any symptoms, but eventually it can severely damage the liver, leading to death without treatment.

“Many young people who are at risk for hepatitis C may acquire the infection and then not know it, and then through drug injection practices may transmit it to others,” said Brandon Marshall, associate professor of epidemiology in the Brown University School of Public Health and corresponding author of the new study in the Journal of Adolescent Health. “For this reason, we need to not only be screening, but also providing care to young people who test positive for hepatitis C.”

Between January 2015 and February 2016, the researchers recruited 196 people between the ages of 18 and 29 from the streets of Rhode Island who use prescription opioids recreationally, rather than for medical reasons. Of those, 154 (78.6 percent) reported receiving HCV screening, which Marshall said was a high and encouraging rate. That said, the proportion receiving screening was much higher among those ages 24 to 29 (89.5 percent) than among those ages 18 to 23 (59.7 percent), he noted.

Among those who were screened, 18 said they tested positive for HCV, which was 30 percent of the 59 people in the study who said they have injected drugs. When study staff asked about follow-up care, they found several gaps: Among the 18 with a positive test, 13 received a confirmatory follow-up test, 12 were referred for specialty care, only 10 received information about how not to transmit the virus to others, and nine received education about living with HCV.

“Screening for HCV is free in many parts of the state, but financial and other barriers exist for youth who test positive and are in need of additional resources and hepatitis C care,” Marshall said. “We need to work on improving access to hepatitis C treatment programs and other referral services for young people.”

Co-author Dr. Lynn Taylor, an associate professor of medicine at Brown and physician at the Miriam Hospital, said the clear overlap of opioid use and hepatitis C infection requires a tightly coupled public health effort.

“This work points to our next steps: We must act to integrate overdose and hepatitis C prevention in Rhode Island,” Taylor said. “In locales where people are injecting opiates, there are an estimated five new hepatitis C infections for every fatal overdose. Rhode Island is the ideal state to address the connections between the opioid and hepatitis C crises and demonstrate the benefits that are possible for public health preventive efforts.”

Brown University School of Public Health graduate alumnus Ayorinde Soipe led the study. Other authors include Ajibola Abioye, Traci Green and Dr. Scott Hadland.

The National Institutes of Health funded the Rhode Island Young Adults Prescription Drug Study (grant R03-DA03770), from which the data were derived, and provided additional funding (P30AI042853).