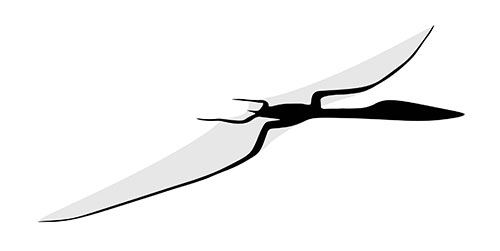

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Most renderings and reconstructions of pterodactyls and other extinct flying reptiles show a flight pose much like that of bats, which fly with their hind limbs splayed wide apart. But a new method for inferring how ancient animals might have moved their joints suggests that pterosaurs probably couldn’t strike that pose.

“Most of the work that’s being done right now to understand pterosaur flight relies on the assumption that their hips could get into a bat-like pose,” said Armita Manafzadeh, a Ph.D. student at Brown University who led the research with Kevin Padian of the University of California, Berkeley. “We think future studies should take into account that this pose was likely impossible, which might change our perspective when we consider the evolution of flight in pterosaurs and dinosaurs.”

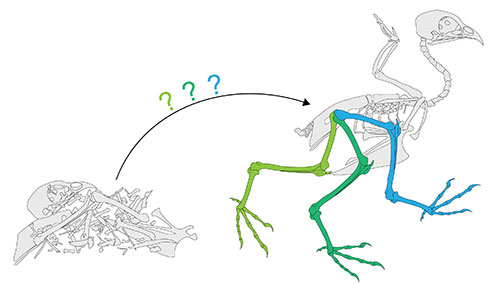

The research, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is an effort to help paleontologists infer the range of motion of joints in a way that takes into account the soft tissues — particularly ligaments — that play key roles in how joints work. Generally, soft tissues don’t fossilize, leaving paleontologists to infer joint motion from bones alone. And there aren’t many constraints on how that’s done, Manafzadeh says. So she wanted to find a way to use present-day animals to test the extent to which ligaments limit joint motion.

It’s an idea that started with grocery store chickens, Manafzadeh says.

“If you pick up a raw chicken at the grocery store and move its joints, you’ll reach a point where you’ll hear a pop,” she said. “That’s the ligaments snapping. But if I handed you a chicken skeleton without the ligaments, you might think that its joints could do all kinds of crazy things. So the question is, if you were to dig up a fossil chicken, how would you think its joints could move, and how wrong would you be?”

For this latest study, she used not a grocery store chicken, but dead quail. Birds are the closest living relative of extinct pterosaurs and four-winged dinosaurs. After carefully cutting away the muscles surrounding the birds’ hip joints, she manipulated the joints while taking x-ray videos. That way, she could determine the exact 3-D positions of the bones in poses where the ligaments prevented further movement.

This technique enabled Manafzadeh to map out the range of motion of the quail hip with ligaments attached, which she could then compare to the range of motion that might have been inferred from bones alone. For the bones-only poses, Manafzadeh used traditional criteria that paleontologists often use — stopping where the two bones hit each other and when the movement pulled the thigh bone out of its socket.

She found that over 95 percent of the joint positions that seemed plausible with bones alone were actually impossible when ligaments were attached.

The next step was to work out how the range of motion of present-day quail hips might compare to the range of motion for extinct pterosaurs and four-winged dinosaurs.

The assumption has long been that these creatures flew a lot like bats do. That’s partly because the wings of pterosaurs were made of skin and supported by an elongated fourth finger, which is somewhat similar to the wings of bats. Bat wings are also connected to their hind limbs, which they splay out widely during flight. Many paleontologists, Manafzadeh says, assume pterosaurs and four-winged dinosaurs did the same. But her study suggests that wasn’t possible.

In quail, a bat-like hip pose seemed possible based on bones alone, but outward motion of the thigh bone was inhibited by one particular ligament — a ligament that’s present in a wide variety of birds and other reptiles related to pterosaurs. No evidence, Manafzadeh says, suggests that extinct dinosaurs and pterosaurs wouldn’t have had this ligament, too.

And with that ligament attached, this new study suggests that the bat-like pose would be impossible. According to Manafzadeh’s work, this pose would require the ligament to stretch 63 percent more than the quail ligament can. That’s quite a stretch, she says.

“That’s a huge difference that would need to be accounted for before it can be argued that a pterosaur or ‘four-winged’ dinosaur’s hip would be able to get into this bat-like pose,” Manafzadeh said. And that, she says, may require a rethinking of the evolution of flight in these animals.

In addition to calling into question traditional ideas about flight in pterosaurs and early birds, the research also provides new ways of assessing joint mobility for any joint of any extinct species by looking at its living relatives.

“What we’ve done is to provide a reliable way to quantify in 3-D everything a joint can do,” Manafzadeh said.

She hopes other researchers will use the method to study other joint systems and to better understand how other species may have moved their joints, walked and flown.

The research was supported by the Bushnell Research and Education Fund, Sigma Xi (G2016100191859492), Uplands Foundation and the Sakana Foundation.