PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Starting in the 1980s, the number of multiple births — twins, triplets, quadruplets and quintuplets — steadily increased from about 20 sets per 1,000 live births to almost 35 sets per 1,000 live births in the 2010s.

That trend presents some concerns, says Dr. Eli Adashi, professor of medical science at Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School — multiple births come with various medical risks to both mother and babies, chief among them the risk of premature birth.

Adashi and colleague Roee Gutman, an assistant professor of biostatistics at Brown’s School of Public Health, analyzed Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) birth data to determine how much of this surge in multiple births is the natural result of women choosing to have children later in life — as compared to assisted reproductive technologies, to which the phenomenon is most commonly attributed.

Their results were published on Tuesday, Sept. 11, in the October issue of the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Adashi has a long history of analyzing the sources of multiple births. Until he met a colleague’s natural quadruplets, however, Adashi controlled for maternal age in his analyses but didn’t focus on the role that delayed childbearing may have on the boom of twin, triplet and quadruplet births.

“Our question was: Does this social phenomenon of delayed childbearing have an impact on the incidence of multiple births in the United States?” Adashi said. “In the paper, we showed that yes, indeed, not all the multiple births out there have to do with fertility drugs or in-vitro fertilization (IVF). There’s a sizable proportion of multiple births that are attributable simply to delaying childbearing. And the percentage of these spontaneous multiples seems to be growing.”

The fact that older women are more likely to have twins, triplets and quadruplets has been known for quite some time, Adashi said. In fact, he found a 150-year-old medical paper on the topic. But while the role that delayed childbearing plays in the increase in multiple births from the 1980s onward has been observed, it hadn’t been analyzed with reference data allowing statistical projections until now, he said.

Using CDC data from 1949 to 1966, before assisted reproductive technologies were available, the researchers found that by the time white women reach age 35, they are about three times more likely to have fraternal, non-identical twins. African American women are four times more likely to have twins at age 35. The risk for triplets and quadruplets goes up four and a half times and six and half times, respectively.

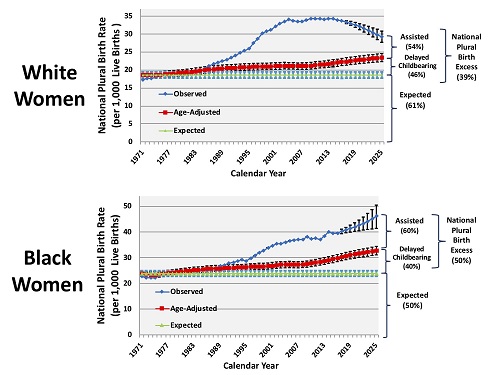

In addition to the advent of assisted reproductive technologies, the study noted that the period of 1971 to 2016 also brought pronounced social changes and more choices by families to delay childbearing. The study found that the fraction of white mothers who were between 30 and 40 years old increased from 16 percent in 1971 to 42 percent in 2015. Black mothers of this age increased from 14 percent to 31 percent over the same time period. The researchers found that this increase in the number of older women having children without assisted reproductive technologies played a definite role in the number of multiple births that exceeded the expected rate of about 20 multiples per 1,000 live births.

In 2016, delayed childbearing was solely responsible for 24 percent of the multiple births for white women beyond expected rates and 38 percent for black women. Furthermore, by extrapolating delayed childbearing rates, the researchers projected that by 2025, women having children later without using assisted reproductive technologies could account for 46 percent of the excess multiple births for white women and 40 percent for black women.

Adashi said the goal of the research is not to intrude upon personal choices about how and when to have families, but to understand the factors that have contributed to the surge in multiples and raise awareness of the risks of delayed childbearing.

“People need to be aware of the increased risk of multiple births among the other more established concerns for advanced maternal age, such as Down syndrome, preterm birth and pre-eclampsia,” he said.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (DMS-1557466). In addition to co-authors Adashi and Gutman, the late Frank Kellerman of Brown’s Sciences Library provided technical assistance.