PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In honor of two trailblazing black graduates, Brown University will rename one of the most heavily-trafficked buildings in the heart of its College Hill campus as Page-Robinson Hall.

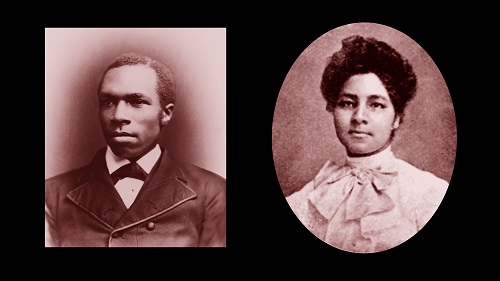

The six-story academic and administrative facility at 69 Brown St. is currently known as the J. Walter Wilson building, home to a variety of student-focused offices and services. It will be renamed for Inman Edward Page — who, with a classmate, became one of the first two black graduates of Brown in 1877 — and Ethel Tremaine Robinson, who earned her degree in 1905 as the first black woman to graduate from the University.

Brown President Christina Paxson announced the name change among a gathering of more than 600 alumni of color and their families on Saturday, Sept. 22, during the University’s Black Alumni Reunion weekend.

“Inman Page was born into slavery, sought liberty and opportunity and found them at Brown — and he saw the power of education to cultivate the innate ‘genius’ in everyone,” Paxson said. “Ethel Robinson broke a color barrier and a glass ceiling when she graduated from Brown in 1905. Together, these two pioneers embodied the faith in learning, knowledge and understanding that has animated Brown for generations.”

Paxson said the University decided to memorialize the contributions and the struggles of black alumni through this building renaming in recognition of the historic significance of this year. The year 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of 1968, a time of upheaval in the Civil Right Movement, including the assassination of The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and major black student walkouts and civil actions at universities across the country, including at Brown.

Given the historical and academic significance of this renaming, the University undertook a deliberate process in determining the right building to bear the new designation, Paxson said.

“We wanted a building at the heart of campus that every student, faculty member and staff member uses on a regular basis,” she said. “And one that serves as a center of classroom activity, teaching and learning — the core of the Brown experience.”

Originally built as a home for life sciences laboratories, J. Walter Wilson Laboratory opened in 1962. After a top-to-bottom renovation in 2008, the building no longer serves as laboratory space. Today, it is home to a range of central services that include the financial aid office, the office of international student and scholar services, the mail center, the chaplain’s office, transportation and parking for the campus, and the University cashier, as well as classrooms and seminar rooms.

James Walter Wilson, the building’s namesake, served as a beloved professor of biology at Brown for more than four decades, helping the Department of Biology achieve a national reputation for research and teaching. An accomplished researcher who studied kidney function, cytology and cancer in animal tissues, he was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and president of the American Society of Zoologists. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy invited him to speak at the President’s Conference on Heart Disease and Cancer.

A plaque in the renamed building will honor Wilson’s enduring legacy at Brown.

The target date for formally implementing the Page-Robinson Hall name change throughout various campus maps and business systems will coincide with the start of the Spring 2019 semester at Brown.

A significant milestone

Highlighting the achievements of two black alumni by renaming such a prominent building is a significant milestone for the University, Class of 1968 alumna Bernicestine McLeod Bailey said.

When McLeod Bailey studied at Brown, she was one of only a few dozen black students on campus. Although she was actively involved in seeking greater representation for the University’s students of color, she never encountered any mention of Page or Robinson during her undergraduate years on campus.

In the years since her graduation, McLeod Bailey has served as a Brown trustee and on the board of governors for the University’s Inman Page Black Alumni Council (IPC). Currently, she is leading an effort to create a comprehensive archive of materials related to the history of the black community at Brown. The Page-Robinson Hall renaming, she said, exemplifies the University’s commitment to reclaiming and elevating that history.

“We have a history here — a notable history,” McLeod Bailey said. “And it is something that should be celebrated and recognized by the whole community. By renaming this building, Brown is embracing us as part of its official narrative.”

Harold Bailey — McLeod Bailey’s husband, a former Brown trustee and member of the IPC board of governors — took part in the 1968 Black Student Walkout, when 65 students boycotted classes for nearly a week to protest what they viewed as a lack of commitment to black students at Brown.

Bailey, who graduated in 1970 and later received an honorary degree from Brown, said the location of Page-Robinson Hall adjacent to Faunce Arch is particularly poignant. It was there that the black women from Pembroke College met up with black men from Brown at the Faunce House tunnel before they left the campus together in protest.

Bailey had attended segregated schools in Tennessee and said he had no illusions about the potential consequences of the Walkout.

“When we walked through that tunnel, we knew it might be our last time,” Bailey said. “It was a big risk. You don’t forget what you went through. To have the newly named building in this particular place means a tremendous amount.”

Sheryl Brissett-Chapman, a student leader during the 1968 Black Student Walkout and past president of the IPC, said the stories of Page and Robinson resonate deeply for her. The great-granddaughter of slaves, Brissett-Chapman earned her degree in theatre arts and English at Brown and co-founded Brown’s Rites and Reason Theatre, now one of the oldest continuously producing black theatre companies in the nation.

She said the renaming both honors the contributions made by individuals whose cultures have not been historically celebrated and recognizes the challenges faced by students of color at Brown.

“Page-Robinson Hall symbolizes the opportunity for me, and others, to put closure on a past that was painful and difficult here,” Brissett-Chapman said. “The renaming honors, respects and reinforces black history at Brown for the entire University. It will embolden and give rise to our ability to forgive, to engage and to discover a true Brown legacy.”

Lives of distinction

Born in Virginia, Page graduated from Brown in 1877. He was elected class orator, giving a speech at Commencement that was noted in the Providence Journal for its intellectual power and eloquence. Robinson excelled in her studies, graduating with honors in 1905 with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy degree and winning the Class of 1873 Prize Essay competition.

After their respective graduations from Brown, both Page and Robinson proceeded into lives and careers as influential educators.

Page dedicated his life to promoting higher education opportunities for African Americans in the American South. He served as president of four historically black colleges and universities: the Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma; Western Baptist College in Macon, Missouri; Roger Williams University in Nashville, Tennessee; and the Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, Missouri.

In 1918, then-Brown President William H.P. Faunce conferred upon Page an honorary master’s degree, citing him as a “teacher, organizer, college president, whose constructive work is… not forgotten by his Alma Mater.”

While in his 70s, Page served as principal of Oklahoma City’s Frederick Douglass High School, where he greatly influenced novelist Ralph Ellison, a student there at the time. According to Brown records, after Page’s death in 1935 at age 82, one newspaper editorialist wrote: “Old Man Ike, as his pupils endearingly referred to him, was a terror to the disobedient and the mischievous. This was not because of any cruel penalties he visited upon them, but because his students abhorred the thought of their idol knowing of their delinquency. It was this peculiar hold that he had upon youth which wove out of the fabric of their lives virtue and strength of character.”

Though Robinson’s life is not as well documented as Page’s, she paved the way for many other black women at the University, including her younger sister Cora, who graduated in 1909. Returning to her hometown of Washington, D.C. after earning her Brown degree, Robinson taught English and literature at Howard University. In 1908, she mentored Howard student Ethel Hedgeman Lyle in her efforts to found the nation’s first black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, which now has nearly 300,000 members.

After leaving Howard University, Robinson married Joaquin Pineiro, a member of the Cuban diplomatic mission to the United States, in 1914. The couple then moved to France, where Pineiro was appointed chancellor of the Cuban Consulate in Bordeaux, coming home to the United States in 1916 after the start of WW-I. Upon her husband’s death, Robinson returned to Providence, where her sister Cora’s descendants still live.

In 2017, Jenna Laycraft, a graduate student in American studies at Brown, painted a portrait of Robinson as part of her research into the subjects pictured in, and omitted from, the Brown Portrait Collection. The portrait, based on Robinson’s photo in Brown’s Class of 1905 yearbook, hangs in the University’s Faculty Club.