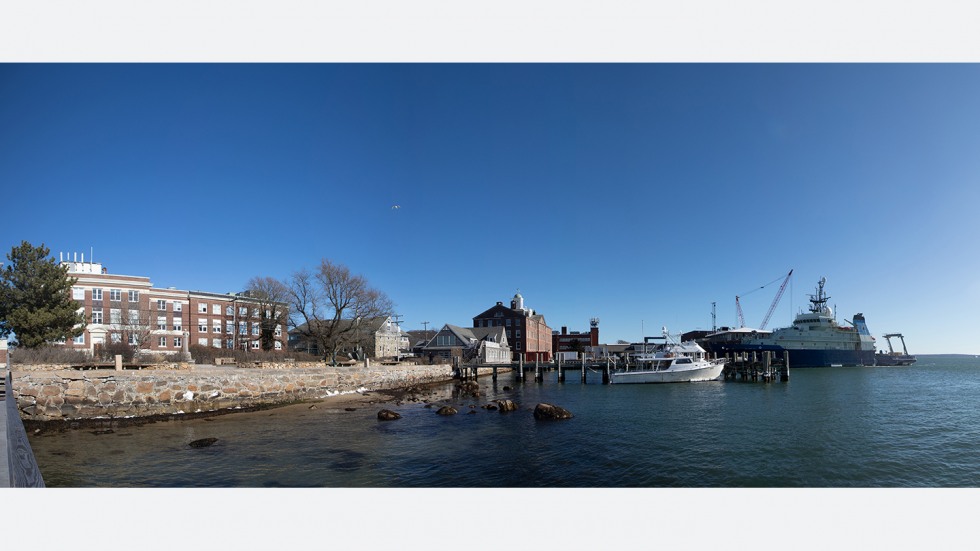

PROVIDENCE, R.I.[Brown University] — It’s a bitter cold morning in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

By 9 a.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 22, the temperature has risen to 17 degrees. Factor in the 20-mph winds that whip into the small Cape Cod village from the waters of Vineyard Sound, and the temperature with wind chill registers 0 degrees — downright balmy compared to the previous day, which reached a high of 6 degrees, wind chill excluded.

But a hardy group of faculty members and graduate students from Brown University’s neuroscience department don’t let the frigid temperatures faze them.

They are at an immersive workshop, or practicum, held at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL). The NeuroPracticum is a nine-day workshop with hands-on rotations where a dozen first-year graduate students explore everything from the activity of a single calcium ion channel — a protein critical for transmitting signals within the nervous system, including triggering the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and acetylcholine — to tracking the behavior of worms.

“The academic goal of NeuroPracticum is to be able to put into practice all of this theoretical knowledge the students have been learning in classes about how neurons work, how people do science and how experiments are run,” said Anne Hart, professor and vice chair of the neuroscience department.

“There’s nothing like putting your hands on something to understand how it works.”

‘Failure teaches, too’

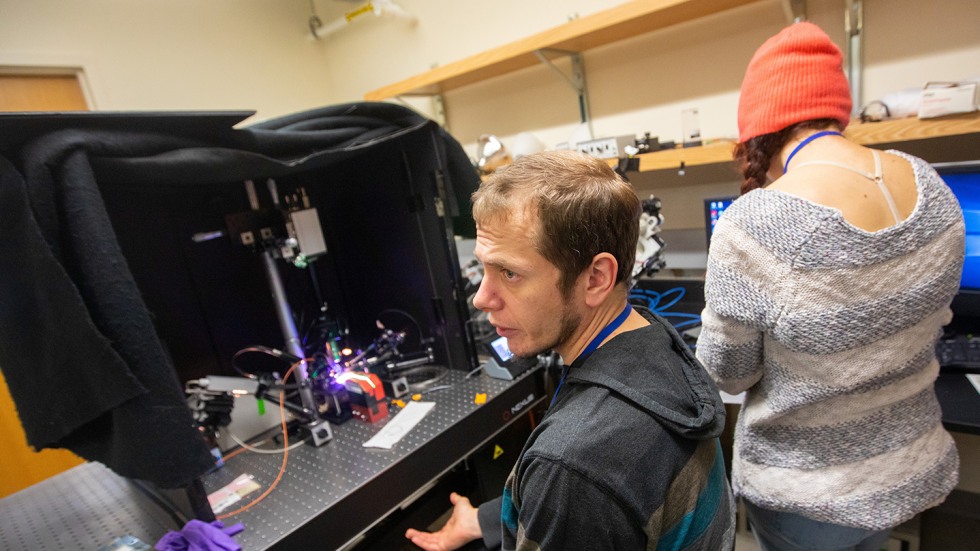

One of the four two-day rotations the students complete focuses on electrophysiology — the study of the electrical properties of biological cells and tissues. The rotation is led by Diane Lipscombe, a neuroscience professor who directs the Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science and is president of the International Society for Neuroscience, and Scott Cruikshank, associate professor of neuroscience (research).

Lipscombe and teaching assistant Javier Lopez-Soto, a postdoctoral fellow in her lab at Brown, instruct the students on how to use a patch-clamp method to record the activity of a single calcium ion channel in real time. Cruikshank shows the students how to record activity from brain slices from a mouse genetically engineered so that specific neurons are sensitive to light.

Kelsey Babcock, a first-year neuroscience graduate student, says the opportunity at NeuroPracticum to put into action a concept she spent her first semester studying in the classroom is immensely valuable.

“We talked a lot about electrophysiology in class,” Babcock said, “but now I’ve actually patched living cells and changed the voltage to observe how channels react.”

Both Lipscombeand Cruikshank use custom instruments they assembled mere days earlier specifically for the NeuroPracticum. They brought some elements of the setup from Brown, some they are borrowing from MBL and others are on loan from equipment manufacturers, Cruikshank said. Since the equipment is somewhat improvised, they take turns showing the groups of three or four students how to conduct the experiments and trouble-shoot, Lipscombe said.

Hart says that the faculty want to be clear with students that “not everything works in science.”

“Failure teaches, too,” she said. “That is part of the learning experience. Even if one of our projects fails in some aspect, the students see us changing this or doing that on the fly. And they see us undaunted.”

Hands-on rotations

Another rotation introduces students to voltage-sensitive imaging and optogenetics — methods of watching or controlling brain cells using light — in living mice. Over two days, students experiment to determine if moving a mouse’s whiskers impacts the endothelial cells in certain brain regions. Endothelial cells are the cells on the inside of blood vessels that form the blood-brain barrier, a highly selective border that separates circulating blood from the brain.

Chris Moore, a Brown neuroscience professor who leads the rotation and associate director of the Carney Institute, is interested in new evidence that the blood-brain barrier is not as permanent a barrier as taught in textbooks. Teaching assistants Sinda Fekir and Eric Klein, third-year graduate students in his lab, assisted him in developing the NeuroPracticum experience — they helped build and program the custom experimental setup and once the practicum was underway, worked with first-year students to explain the experiment’s complete life cycle, from designing an experimental rig to analyzing data from the resulting brain activity video.

A third rotation explores worm behavior, comparing the rest and activity patterns of normal C. elegans — transparent worms about as long as a pinhead — and genetically engineered worms that contain a mutation found in some people with ALS. This rotation is led by Hart. The first-year students gain hands-on experience in everything from determining the age and sex of worms to basic molecular biology — used to visualize specific neurons, said Katie Yanagi, a fourth-year graduate student in Hart’s lab and teaching assistant.

Yanagi has attended NeuroPracticum three times. She attended as a first-year student, conducted her own research project as a third-year and now serves as a teaching assistant for Hart.

“Each year was a different experience,” Yanagi said. “The first time I really enjoyed turning my theoretical understanding of electrophysiology into a hands-on experience. Last year, my individual project was great — I got to study octopus chromatophores, something I wouldn't have gotten a chance to do normally. Now I get to help first-years with hands-on biology techniques.”

The fourth rotation is a deep dive into MatLab data analysis led by Jason Ritt, a visiting faculty member for the practicum from Boston University. During his two-day rotation, the students use audio files as a proxy for more traditional neuroscience data while learning how to use the software and select thresholds to improve signals and reduce noise.

Rachel McLaughlin, a first-year neuroscience graduate student, found the data analysis rotation to be most valuable rotation thus far.

“We got to use MatLab to analyze data such as parsing words in an audio file and analyzing the pitch of different vowels,” McLaughlin said. “The best part was at the end we got to use MatLab to make a mixtape of the sounds.”

Community building

Providing hand-on experience isn’t the only goal of NeuroPractium, Moore said. Equally important is the opportunity to introduce first-year graduate students to the neuroscience community and facilitate informal interactions with faculty.

Hart and Moore began the NeuroPracticum in January 2013 and the choice to base it at MBL is rooted directly in their community-building goal — the institution is far enough from Providence to allow for an immersive experience that’s different from life and study on College Hill, which is essential, Moore added.

“I rarely get a chance to just sit around with students, because I’m always doing something else,” Moore said. “I can’t do something else, because I’m in Woods Hole. Even if I’m working on my computer, I’m in the same room as the students and they can walk up and ask me about careers.”

That is what first-year student Isabella Penido found most rewarding about the NeuroPracticum.

“I like talking to the professors and postdocs about career advice,” she said. “How did they get funded, how to stand out, how long to be a postdoc, topics like that.”

Hart said that evening activities as simple as meals in town or ventures out for candlepin bowling encourage the full contingent of neuroscientists to relax and recharge before diving into the next rotations. Such informal interactions also help the students realize that the faculty are humans, too, which makes the idea of becoming neuroscientists and professors more accessible, she added.

“I love the environment they’ve created at NeuroPractium,” said Tariq Brown, a first-year neuroscience graduate student. “There are fountains of knowledge all around us.”