PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Did you know that there are more connections between neurons in one human being than there are galaxies in the universe?

That is Alastair Tulloch’s favorite brain fact. Tulloch is a doctoral candidate studying neuroscience at Brown University — and through the annual Brain Week Rhode Island celebration, he has worked for the past four years to make brain science insights like that one accessible to people across the state.

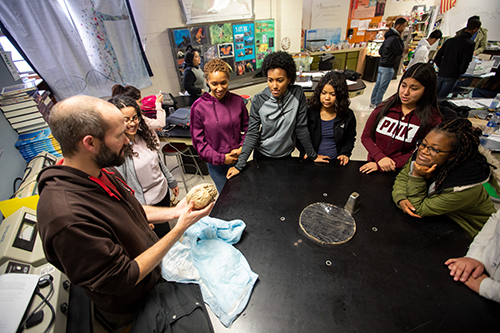

On an early March morning, he stands in front of David Upegui’s Advanced Placement biology class at Central Falls High School showing students a plasticized human brain — the brain from an individual who donated their body to science, treated such that each nook and cranny is hardened into safe-to-touch plastic.

This classroom visit is one of 14 planned at local schools — a few were cancelled due to winter weather — by Brown neuroscience graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and medical students in the two weeks preceding Brain Week R.I.

The week, which aims to make brain research fun, educational and accessible to everyone, kicks off on Saturday, March 9, and runs through the Brown Brain Fair on Sunday, March 17. It is organized by the Providence-based national advocacy organization, Cure Alliance for Mental Illness, and is sponsored by the Carney Institute for Brain Scienceat Brown and the Ryan Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rhode Island.

The visit to Central Falls High begins with John Stein, a senior lecturer in neuroscience, leading the students through the basics of what happens in the nervous system when someone steps on a tack — a sensory input — which results in them lifting their foot — a motor response — before they can even say “ow.”

Stein advances his slideshow, and a photo of a lioness staring through tall grass pops up. He asks the class for the correct motor response for this sensory input.

“Run!” shouts a student.

“Don’t run,” another chimes in.

“Play dead,” says a third.

Stein encourages the class to discuss the options before he moves to his next point: Unexpectedly encountering a lioness requires a complex response, and unlike when someone steps on a tack, neuroscientists don’t fully understand what occurs in the brain during such complex decision-making. That is what makes neuroscience research so interesting, he asserts.

From there, Tulloch, Maya Ayoub (a student at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School) and Abdullah Rashed Ahmed (a first-year neuroscience graduate student) tell their own stories, sharing with the high schoolers how they became interested in the brain.

Ayoub took a neuroscience class the summer after her junior year in high school, which started her down her current path. She intends to focus on child neurology during her residency.

Rashed Ahmed became interested in the brain while studying computer science. Modern computers may be faster than human brains at mathematical calculations, but for many things they just cannot compare, he says.

Nick Dentamaro / Brown University

Tulloch was drawn to the complexity of the brain and its countless connections. For his thesis work, he studies how the brain wires itself during development.

The class divides into groups, and the students grow quiet as the Brown visitors pull well-wrapped objects out of metal boxes. The room echoes with “oohs” of interest and “ewws” of aversion as the visitors unwrap the plasticized human brains. They pass the brains around, allowing the high schoolers to opt into holding or touching them.

One student asks about an odd flap covering the back of the brain. Tulloch explains the dura mater, a membrane between the brain and the skull that protects the brain and helps to keep the cerebrospinal fluid in.

This leads another student to ask about a baby’s soft spot. Ayoub explains that the fontanelle is a gap between the bones that make up a baby’s skull, allowing the brain to grow rapidly before the skull fuses together.

The Brown visitors point out other features of the brains, guiding the students in identifying them.

Nick Dentamaro / Brown University

Central Falls student Nathalee Pacheco-Paneto correctly identifies the grooved lobe at the bottom of the brain as the cerebellum, which is responsible for maintaining balance, motor control and coordination.

As the class becomes more comfortable, the students’ questions move beyond visible structures of the brain to more complex questions about the subconscious, traumatic memories, PTSD and depression.

When the bell rings, signaling the end of class, several students are reluctant to leave. Pacheco-Paneto found the fact that a baby’s brain and skull continues to grow particularly interesting.

“It’s so great to see how many talented high school students are interested in neuroscience and the brain,” Ayoub said. “Their questions showed how much they are already integrating their own experiences and interests with the importance of neuroscience research. The complexity of their questions, and the creativity of their ideas about neurology, neuropsychiatry and research gives me hope for the future generation of scientists.”

Kaitlin Wilcoxen, a neuroscience doctoral student at Brown, is among the student coordinators for the visits. She says it’s essential, especially at a young age, to introduce students to brain science concepts, given the organ’s role in overall health.

“It controls your movements and your behavior,” she says. “It controls all the things that makes you you. Making people more aware of the brain and its role in controlling behavior and ways of thinking should help to destigmatize mental illness. And also, I think neuroscience is really cool, so I find it really rewarding to share my passion with the kids and perhaps inspire them to take up the work.”

Tulloch echoes that sentiment.

“We can empower the future generation to continue our mission of studying brain science,” said Tulloch, who has also led the Brown Brain Fair organizing committee since 2017. “There is nothing more captivating than having a group of curious students ask intriguing questions about the brain.”