PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — When Alexa Kanbergs came to Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School four years ago, her goal — like any future doctor — was to learn how to treat patients. Yet she was equally interested in the challenging overlap of correctional facilities and health care systems.

“I've always wanted to practice medicine, but I've always wanted to do something more with my M.D. degree than just clinical medicine,” Kanbergs said. “This program has set me up to do that.”

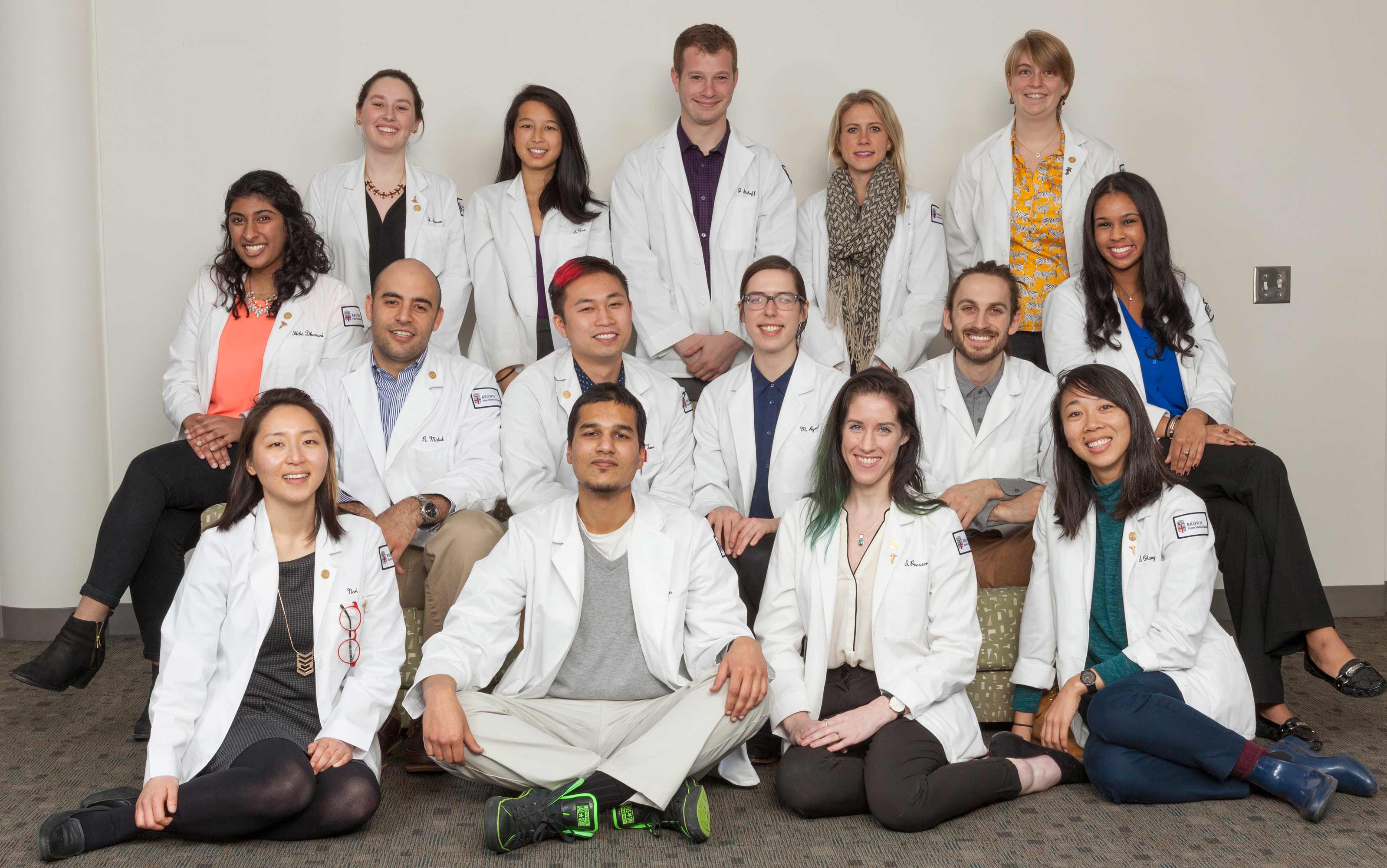

Kanbergs graduated from Brown in May as a member of the University’s first Primary Care-Population Medicine (PC-PM) class, earning both an M.D. and a master of science. In July, she will begin her OB-GYN residency at Harvard.

“It’s not just the courses and the skills that I've gained from those, but the research experience I’ve had, the connections that I've made with individuals who are trying to do the same thing, and the mentorship,” Kanbergs added. “Everyone is very invested in us and in this program.”

The PC-PM program is the first of its kind. Not only is Brown the only school in the nation where a student achieve the two degrees in four years, the program is unique in its combined focus on primary care and population medicine, said Jeff Borkan, a professor of family medicine and assistant dean of the program.

Population medicine focuses on large groups of patients and the health care systems that impact their care. Primary care physicians tend to be the main point of contact for patients within those systems, seeing to day-to-day health challenges and referring them to specialists.

By focusing on both population medicine and primary care, PC-PM prepares students to be future leaders, said Dr. Paul George, associate dean of medical education and director of the program. Students learn how to work within and improve health care systems to care for whole communities and populations, not just individual patients.

“The goal of this program is to provide future physicians with the tools they need in order to succeed in a rapidly evolving health care landscape,” George said. “Physicians have to be facile not only in the clinical care of patients, but also thinking about how to lead health care teams, how to put quality improvement measures in place and how to effectively manage health care resources.”

Critical support for developing and implementing the program came from a $1 million grant from the American Medical Association as part of the Accelerating Change in Medical Education Consortium.

Of the first class of 15 students, nine are starting residency in primary care fields — such as family medicine, internal medicine and pediatrics — in programs across the nation from the University of Washington School of Medicine and the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine to Brown-affiliated programs in Rhode Island. Others will begin residency programs in related fields such as OB-GYN, general surgery and emergency medicine.

“One marker of success is how the students matched with residency programs, but the real marker is what happens in the next 30 to 40 years,” Borkan said. “What will these students do in the future? One of our goals is to be able to track these future leaders of medicine and see how they make their impact.”

Lessons in leadership

One of PC-PM’s primary goals is to train not just physicians, but physician leaders, George said. Sometimes students gain leadership skills learning from health care leaders in class; at other points they build leadership skills in the community and in their clinical settings.

In addition to the fundamental classes that all medical students take, PC-PM students take nine additional courses in population and clinical medicine, research methods, biostatics and epidemiology, health systems sciences and leadership.

Health systems science is a new, third science in medicine that complements basic and clinical science, and includes topics such as how to use an electronic health record, how to communicate and work in teams as well as knowledge of health care financing and policy, Borkan said. Typically, new doctors learn these topics informally or independently, he said — but future physician leaders such as those in the PC-PM program, need a more thorough understanding of the health system. Some of the health systems coursework developed for PC-PM was integrated into the Warren Alpert Medical School’s traditional M.D. program, given the benefit to all future physicians, he added.

A formal leadership course in PC-PM includes lessons on project management, the characteristics of successful leaders, as well as visits from leaders in the field including CEOs of health care companies.

“We decided that leadership skills were a big portion of what we wanted to teach to these folks who are going to be systems workers, advocates and leaders in practice,” Borkan said. “And the students do seem to really benefit from learning health systems science — including leadership — alongside basic science and clinical science.”

Students also learn to lead by teaching, he added, taking on increasing responsibility for teaching one another as they progress through the curriculum. By the fourth year, the students are responsible for selecting topics within health systems science, designing lesson plans and teaching classmates.

“We gave the students some background in educational theory and design and our expectation that they would deliver an exquisite, engaging session — with active learning — on critical elements that they think every student who finished the PC-PM program should know,” Borkan said. “They covered everything from diversity and inclusion to how to produce an advocacy brief to the use of photography in medical and health activism to using geographic information systems for health.”

Julia Solomon, a member of the first PC-PM class who will remain at Brown for the combined internal medicine-pediatrics residency at Rhode Island Hospital, said the capstone course proved valuable.

“At this point we knew each other really well, so getting to see some of the expertise that our classmates had gained over the years in things that they’re interested in and are going to apply to health policy and practice as residents was great,” she said.

Using classroom learning to equip PC-PM students with the tools to conduct research on population medicine is important, George said — but the program doesn’t stop with just classroom instruction.

Instead, each student is matched with a research mentor and learns how to conduct population medicine research by taking on independent projects. Each student prepares their research as a publishable paper, which serves as the student’s master’s thesis.

Kanbergs researched the personal experiences of patients within the Rhode Island correctional system with a focus on inmates with serious conditions such as cancer, poorly controlled diabetes or epilepsy. She surveyed 18 individuals and found that prison co-pays, the availability of physical accommodations — such as wheelchair-accessible cells or prison showers — and variable quality of care were common challenges.

“Going into the project, I wasn't aware that a lot of prison systems have co-pays,” she said. “For a lot of people it was a deterrent in seeking health care, because they didn't want to have to use what little funds they had to pay to see a health care provider. These individuals are often paid, at the maximum, $3 a day, and more often $1 a day, for the job that they're doing in the facility.”

Solomon’s thesis compared the levels of tobacco use and obesity reported in Rhode Island’s All-Payer Claims Database to public health estimates within the state. Other students researched participants’ perceptions of mindfulness in addiction recovery, physician attitudes toward accountable care payment models, and ways to tackle food insecurity among the elderly in Rhode Island.

Building long-term relationships

Imagine a high school where students learn math — and nothing but math — for a month, and then English for a month, followed by a month of social studies. That is the traditional manner in which third-year medical students are introduced to the core specialties of medicine such as internal medicine, family medicine, OB-GYN, pediatrics, surgery, psychiatry and neurology, George said.

Another format, called the longitudinal integrated clerkship, is more like how students learn during high school, where study of different subjects not so discrete. This how the PC-PM students are introduced to the core specialties of medicine in clinical settings. The longitudinal format excels at promoting long-term relationships between students, mentors, their patients and the surrounding community, which is ideal for a program with a focus on primary care, said George and Borkan.

“Primary care is not about quick fixes — it’s more like a fine wine, it gets better over time,” Borkan said. “It’s to our advantage to have students be in their sites over the long term, to be better able to appreciate primary care.”

Third-year medical students in conventional M.D. programs spend six- and 12-week blocks rotating through the core specialties mostly at hospital-based inpatient settings. In the PC-PM program, students spend a half-day each week for about nine months with seven different physician mentors primarily at outpatient clinics.

“It was huge to spend a year at an outpatient obstetrics clinic and really get to know what is my life going be like when I'm an OB-GYN,” Kanbergs said. “It was also an opportunity to build incredible longitudinal relationships, not just with patients — I followed one patient through her entire pregnancy, which was so unique — but I also got to know my mentors very well.”

Kanbergs credits the relationship she was able to build with her OB-GYN mentor for her decision to pursue the specialty during her residency.

“He was able to watch me grow as a physician,” she said. “As he saw that I was able to take on the challenges and tasks, he would allow me more responsibility. By the end, I felt like I was really working with him as a team member.”

Borkan added that the longitudinal format provides students with an in-depth view of how the health system works as they follow and assist their patients as they navigate through it.

In addition to following a patient throughout her entire pregnancy, Kanbergs also supported a woman through the duration of cancer treatment. Kanbergs was present when the woman was diagnosed with anal squamous cell carcinoma. She joined the woman at her appointments with the surgeon, oncologist and radiologist; helped to clarify some of the information they provided her; and even provided social support.

“She ended up being someone I consider a friend,” Kanbergs said. “I just felt like I was there for her when she was going through a really tough time. It was such a unique experience and you don't have that kind of flexibility in a traditional clerkship to be able to follow patients like that. Now, she's doing great.”

Partners in shaping the program

Not only are the PC-PM program’s Class of 2019 members the inaugural graduates, they’ve also been instrumental in shaping its future, Borkan said.

“The first class have been pioneers, and they’ve taken that role seriously,” he said. “They have been active partners in improving it.”

Student-driven improvements range from adjusting course content to greatly expanding the focus on creating doctors who excel at teaching.

“We were the first class and they rearranged things a little bit on our suggestions,” Solomon said. “For example, we used to have a research-methods class the second semester but we all had already picked research topics at that point. So we suggested that we should have methods before we pick our topics and our research approach.”

Subsequent PC-PM classes enrolled up to 24 students, though due to the intense logistics — particularly for the longitudinal clinical experiences in the third year — Borkan said classes of 18 students might be more sustainable in the decades ahead.

“It’s remarkable to have living, breathing students who have successfully completed both their M.D. degrees and their master of science in population medicine,” he said. “And the students themselves are remarkable. They have been incredibly engaged and active as leaders throughout all four years. They are exceptional, altruistic and focused in the direction of primary care and population health.”