PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — At a young age, Anita Shukla thought she wanted to be a doctor.

“But of course, as many engineers say, I also liked the math and all the basic sciences,” Shukla recalled, and, by double majoring in chemical and biomedical engineering as an undergraduate at Carnegie Mellon, she gained perspective about health problems she could solve with engineering expertise.

Today Shukla is using her knowledge and her “obsession with infection” to take on the challenge of reducing infections and combatting drug-resistant diseases. As an assistant professor of engineering and of molecular pharmacology, physiology, and biotechnology at Brown, she is designing practical biomaterials for life-threatening problems.

Part of that work is a focus on hospital-acquired infections, which are among the most significant dangers, accounting for as many as 99,000 deaths each year in the United States. Shukla is targeting catheter-related bloodstream infections, which are the most common type of hospital-acquired infection.

They are a “major burden for hospitals, health care providers, and most of all patients,” she said, with infections that have mortality rates as high as 12% to 25%. They can prolong hospital stays by 10 to 20 days, and increase the cost of care from $4,000 to $56,000 per patient.

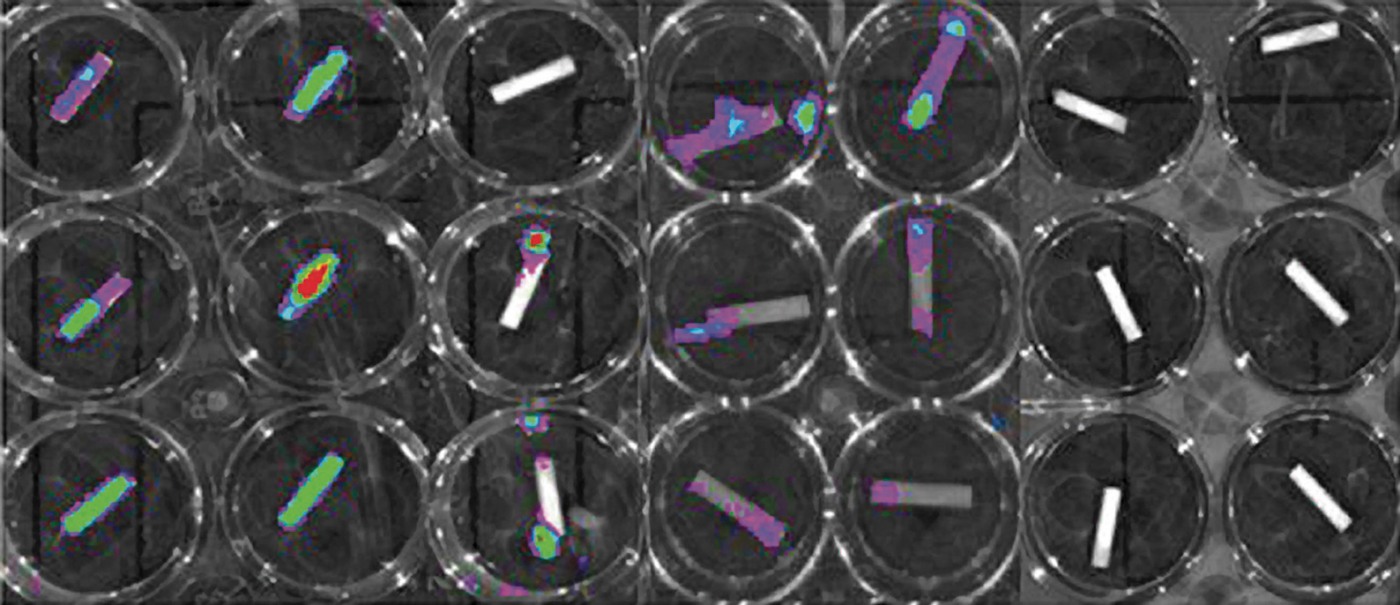

Shukla’s Lab for Designer Biomaterials is collaborating with Rhode Island Hospital to develop a new antibacterial coating for intravascular catheters that aims to combat burdensome, costly and sometimes deadly infections.

“We wanted to develop a coating that could both kill planktonic [free-floating] bacteria and prevent colonization of bacteria on surfaces,” Shukla said.

In their paper published in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, Shukla and her colleagues show that when their polyurethane coating is applied and a drug called auranofin is gradually released, it can kill methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria for nearly a month in lab tests.

“The initial data that we gathered for this paper shows that we have something really promising,” she said.

Shukla’s coating is unique in its use of auranofin. While the drug was originally developed to treat arthritis, it is being found to be also highly effective at killing MRSA and other dangerous microbes. Additionally, unlike a more traditional antibiotic, auranofin works in ways that make it hard for bacteria to evolve a natural resistance.

Research has shown that the coatings had no adverse effects on human blood or liver cells, but more testing is required before the coating is ready to be used on patients. Shukla said, “We’re hopeful that the initial results we show here will soon translate to the clinic.”

Although she received her Ph.D. in chemical engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology just nine years ago and joined the Brown faculty in 2013, Shukla is already accumulating awards as a researcher, teacher and mentor.

In July 2019, she was one of just 314 scholars in the United States to win a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE), the nation’s highest award for scientists and engineers in the early stages of their research careers. She is also the recipient of a Director of Research Early Career Grant from the Office of Naval Research, the office that later nominated Shukla for the PECASE.

“It was a huge honor to be recognized,” Shukla said, adding that the Office of Naval Research “really believes in our work.”

Dean of the School of Engineering at Brown Lawrence Larson called the work of Shukla and her lab “unique and innovative” because it applies concepts from a wide range of fields to develop “biomaterials for critical unmet needs in the areas of drug delivery and regenerative medicine.”

Shukla won a 2017 Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching. Students appreciate the fact that she is always “exceedingly well-prepared and pushes students to think beyond the course material,” said Sarah Cowles, a Class of 2017 alumna who concentrated in chemical and biochemical engineering.

Shukla said her favorite class to teach at the University is ENGN 1110: Biotransport and Transport Processes because of the chance to work with both chemical engineering and biomedical engineering concentrators, mirroring her undergraduate majors.

While they await the results of further testing on the antibacterial coating, Shukla and her lab are working on several other projects.

One centers on fungal infections, a type of infection she thinks does not get enough attention from researchers; her lab is designing a gel-like bandage material made to limit both toxicity and drug resistance. When the bandage is applied to a wound that might contain fungi, if the gel detects the presence of fungi, it releases an antifungal substance into the body. Shukla said this bandage could aid military personnel in the field who cannot be tested for fungus on location.

In addition to her research and teaching, Shukla is an active mentor of students, with a particular focus on advising other women in STEM.

“There really aren’t enough women in engineering and science,” she said. “By being one of those people, and letting others see that I can be successful — that I’m teaching people and acting as a leader — that’s critical. It makes people feel like they can do this too.”