PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — As director of Brown’s Herbarium, the home of about 100,000 plant specimens where some date back to the 1800s, Tim Whitfeld kept running across a mysterious location name: Cat Swamp.

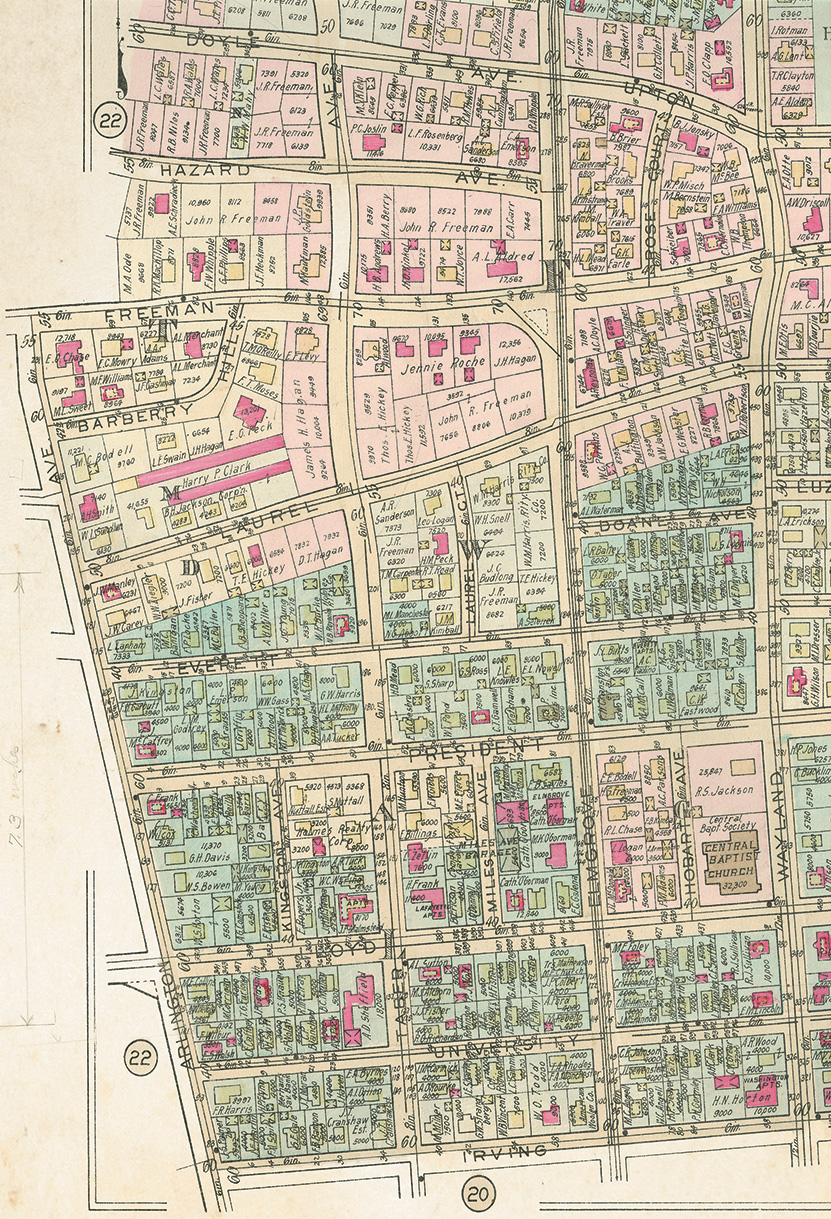

It took more sleuthing, including working with the Rhode Island Historical Society, to figure out more about where the plant samples were from, which turned out to be several blocks of the East Side of Providence, still rural in the 1800s. The marshy area was seen as too difficult and expensive to develop until 1915, when engineers and builders started draining the swamp and constructing many one-family homes in the area.

By the time Whitfeld came upon the specimens, there was no one alive who had seen Cat Swamp, and virtually nobody had ever heard of it. Without records and specimens from the Herbarium, Cat Swamp, with all its distinctive character and plant diversity, would have been lost to history.

Instead, in collaboration with the historical society and the Brown Library, Whitfeld brought the swamp back into public view through “Entwined: Botany, Art and the Lost Cat Swamp Habitat,” an exhibition that attracted several thousand visitors at the John Hay Library in the winter and spring of 2019.

The Brown Herbarium, started in the 1870s, “is a record of plant diversity at a given place at a given time in history,” said Whitfeld. With its collection mostly fully digitized, largely through work by undergraduates, the Herbarium is more accessible than ever to researchers everywhere, and original specimens are safely preserved and available for further study in a modern facility in Brown’s BioMed Center.

The Herbarium has become a key research site for many biologists, students, and others on campus and around the world. And as DNA extraction and analysis techniques continue to become more sophisticated, the Herbarium’s specimens have become even more valuable assets.

Several years ago, the Herbarium launched an ambitious effort to resume collecting current Rhode Island plant specimens. Whitfeld and students collected several hundred new specimens, and, now that Whitfeld has moved to the Bell Museum at the University of Minnesota, the new Herbarium director, Rebecca Kartzinel, is continuing the collecting.

The Herbarium collection has grown through its nearly 150 years, and Kartzinel’s Rhode Island Flora students will help finish the comprehensive collection of Rhode Island’s estimated 1,700 current plant species.

“Scientific collections are super-important for documenting biodiversity,” said Kartzinel, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “In this era of climate change and invasive species,” she said, the Herbarium is an important way to measure what grew when and where, and it increases understanding of environmental trends.

The Herbarium also is used as a research tool to better understand development and pollution locally. Comparing plant specimens at three sites in Providence from 1846 to 1916 to the same sites in 2015, Whitfeld, Class of 2017 alumna Sofia Rudin, and David Murray, a lecturer in Brown’s Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, were able to measure heavy metal pollution and changes over time and publish their work in the journal Applications in Plant Sciences.

While digitized images are making the Herbarium specimens more valuable to researchers outside of Brown, the collection of specimens carefully organized and preserved in climate-controlled cabinets will always be important, Kartzinel said.

“You can’t get DNA out of a photo,” she said. DNA extraction from plants — done by grinding up parts of leaves and then going through filtering steps — has been growing more useful in research, including working to document new species. Kartzinel, whose research focuses on plant population and ecological genetics, plans to expand the use of DNA analysis in the Herbarium, developing a DNA digital database and aiming to add a DNA barcode to specimens to help in identification of species and in cross-referencing that helps determine what was grown in a particular location.

The Herbarium dates to the 1870s, when local businessman Stephen Thayer Olney donated his plant collection to the University. At the same time, William Whitman Bailey became the first botany professor at Brown, and he took over the fledgling Herbarium. He led the collection of many specimens, by himself and by students. Cat Swamp became a favorite location for field trips, as he and students would go there often, and Bailey’s notebooks documenting the visits were part of the John Hay exhibition. Whitfeld said Bailey thought Cat Swamp “was noteworthy in the increasingly urban environment,” and “it was an interesting local hot spot, easy to get to.”

Kartzinel lives on the edge of what was once Cat Swamp. “To walk down there and think there was a swamp there is amazing,” she said.

The Herbarium “is tied to ecological history,” she said, and is also well positioned to provide a window on the environment into the future.