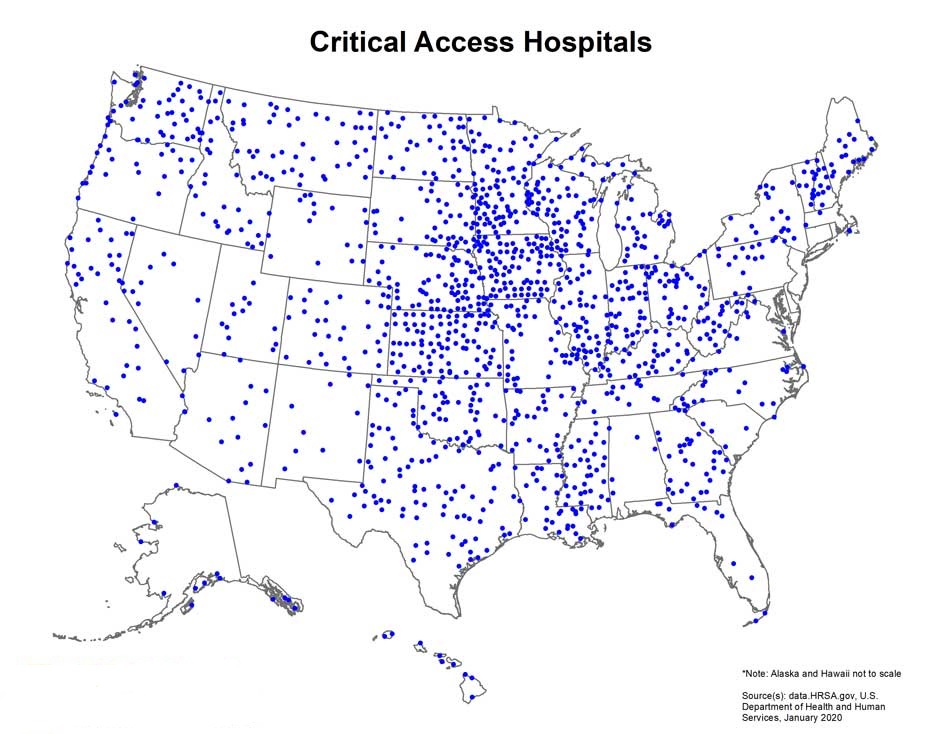

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Critical access hospitals (CAHs) provide care to Americans living in remote rural areas. As important health care access points, these hospitals serve a population that is disproportionately older, impoverished and burdened by chronic disease. In 1997, with small rural hospitals under increasing financial strain and closing in large numbers, the federal CAH designation was established to increase their viability and to ensure that rural communities have adequate access to health care.

Prior research studies comparing the quality of care provided by CAHs and non-CAHs have found that risk-adjusted mortality rates at CAHs were higher, and the hospitals’ quality of care, therefore, lower. But a new study led by investigators at the Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research in Brown’s School of Public Health suggests that standard risk-adjustment methodologies have been unfairly penalizing CAHs.

According to the study, for Medicare beneficiaries in rural areas who were hospitalized during the period of 2007 to 2017, CAHs submitted significantly fewer hospital diagnosis codes than did non-CAHs. The primary reason for the relative under-reporting of diagnoses at CAHs has to do with differences in Medicare reimbursements — while non-CAHs are incentivized by Medicare to complete diagnosis coding, CAHs, which receive cost-based reimbursements, are not.

“When payments for episodes of care are tied to the acuity of patients, health care providers have the incentive to fully report or even overstate acuity,” said study senior author Momotazur Rahman, an associate professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown. “Since payments for non-CAHs are dependent on reported acuity while payments for CAHs are not, non-CAH patients will appear comparatively sicker than they actually are.”

Because mortality rates are adjusted per severity of illness — acuity, in Rahman’s words — the result is that CAHs appear to have higher mortality rates for patients with similar conditions, when in reality their patients may in fact be sicker than those in non-CAHs, from the standpoint of risk adjustment.

The study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on Tuesday, Aug. 4.

How did the researchers determine that CAHs tend to overreport diagnoses? In 2010, Medicare increased the allowable number of billing codes for hospitalizations from 10 to 25.

“We observed a large jump in reported acuity among non-CAH patients in 2010,” Rahman said, “but we saw a much smaller jump for CAH patients. We found that due to this difference in acuity reporting, when compared to non-CAHs, the risk-adjusted performance of CAHs on short-term mortality measures looks much worse than it actually is.”

The CAH program, created to prevent rural hospitals from closing, has repeatedly come under threat. Given that in many parts of the U.S., CAHs serve as sole health care providers, Rahman said that examining differences in quality of care is important for understanding the value of the CAH program and informing decisions about the allocation of funding for rural health care.

The finding that short-term mortality outcomes at rural CAHs may not differ from those of non-CAHs after accounting for different coding practices, he added, is essential knowledge for ensuring timely access to acute care for vulnerable rural communities.

Other authors include Brown doctoral student Cyrus Kosar, the study’s lead author, and Lacey Loomer, Kali Thomas, Elizabeth White and Orestis Panagiotou.