PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A research team from Brown University has made a major step toward improving the long-term reliability of perovskite solar cells, an emerging clean energy technology. In a study published in the journal Science, the team demonstrates a “molecular glue” that keeps a key interface inside cells from degrading. The treatment dramatically increases cells’ stability and reliability over time, while also improving the efficiency with which they convert sunlight into electricity.

“There have been great strides in increasing the power-conversion efficiency of perovskite solar cells,” said Nitin Padture, a professor of engineering at Brown University and senior author of the new research. “But the final hurdle to be cleared before the technology can be widely available is reliability — making cells that maintain their performance over time. That’s one of the things my research group has been working on, and we’re happy to report some important progress.”

Perovskites are a class of materials with a particular crystalline atomic structure. A little over a decade ago, researchers showed that perovskites are very good at absorbing light, which set off a flood of new research into perovskite solar cells. The efficiency of those cells has increased quickly and now rivals that of traditional silicon cells. The difference is that perovskite light absorbers can be made at near room temperature, whereas silicon needs to be grown from a melt at a temperature approaching 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Perovskite films are also about 400 times thinner than silicon wafers. The relative ease of the manufacturing processes and the use of less material means perovskite cells can be potentially made at a fraction of the cost of silicon cells.

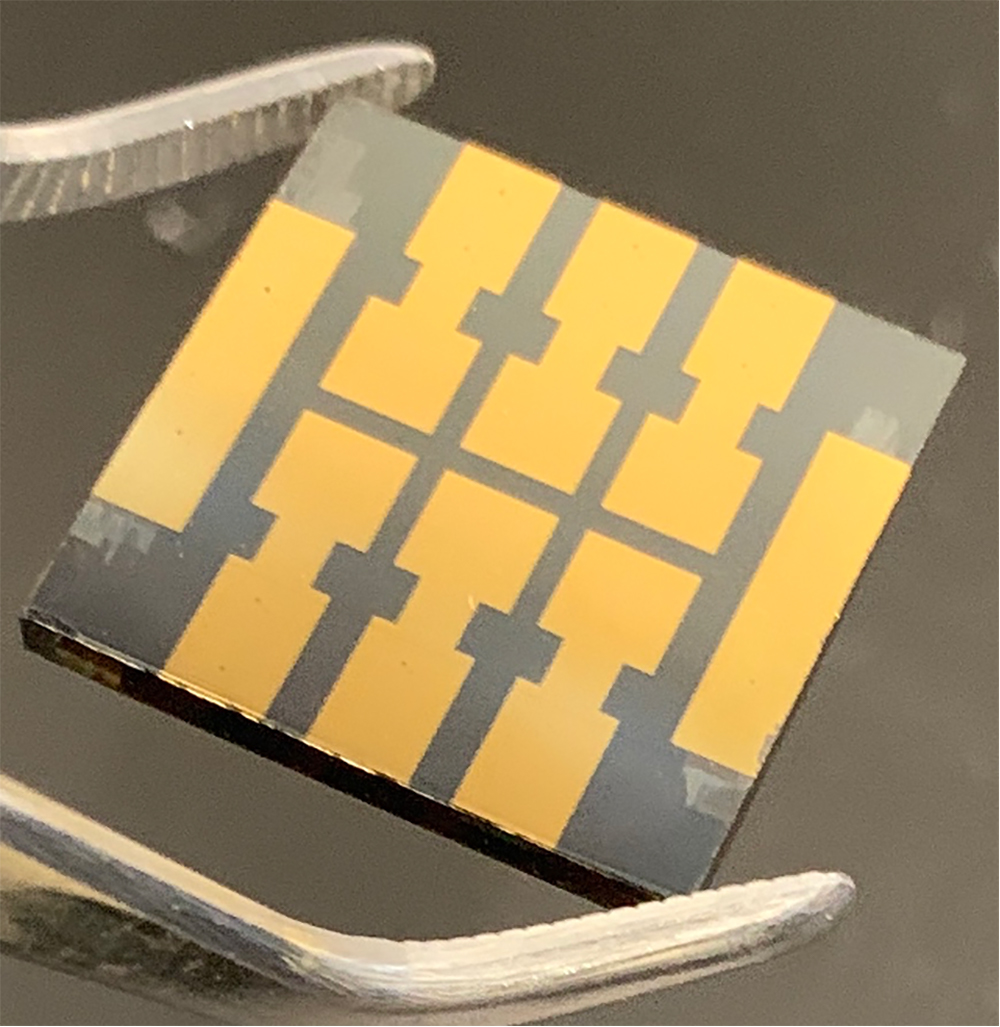

While the efficiency improvements in perovskites have been remarkable, Padture says, making the cells more stable and reliable has remained challenging. Part of the problem has to do with the layering required to make a functioning cell. Each cell contains five or more distinct layers, each performing a different function in the electricity-generation process. Since these layers are made from different materials, they respond differently to external forces. Also, temperature changes that occur during the manufacturing process and during service can cause some layers to expand or contract more than others. That creates mechanical stresses at the layer interfaces that can cause the layers to decouple. If the interfaces are compromised, the performance of the cell plummets.