PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — At first, Apollo 15 astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin didn’t quite believe what they were seeing. During an excursion in their lunar rover — the first such vehicle deployed to the Moon — the astronauts spied flecks of green breaking the grayish white monotony of the lunar surface.

“[Are you] sure it’s green and not just white albedo again?” Irwin asked, referring to the tricks sunlight can play on the lunar surface.

“No, it’s green,” Scott confirmed.

Knowing they had something interesting, Scott and Irwin quickly added a few samples to their collection, which returned to Earth along with the Apollo 15 crew 50 years ago.

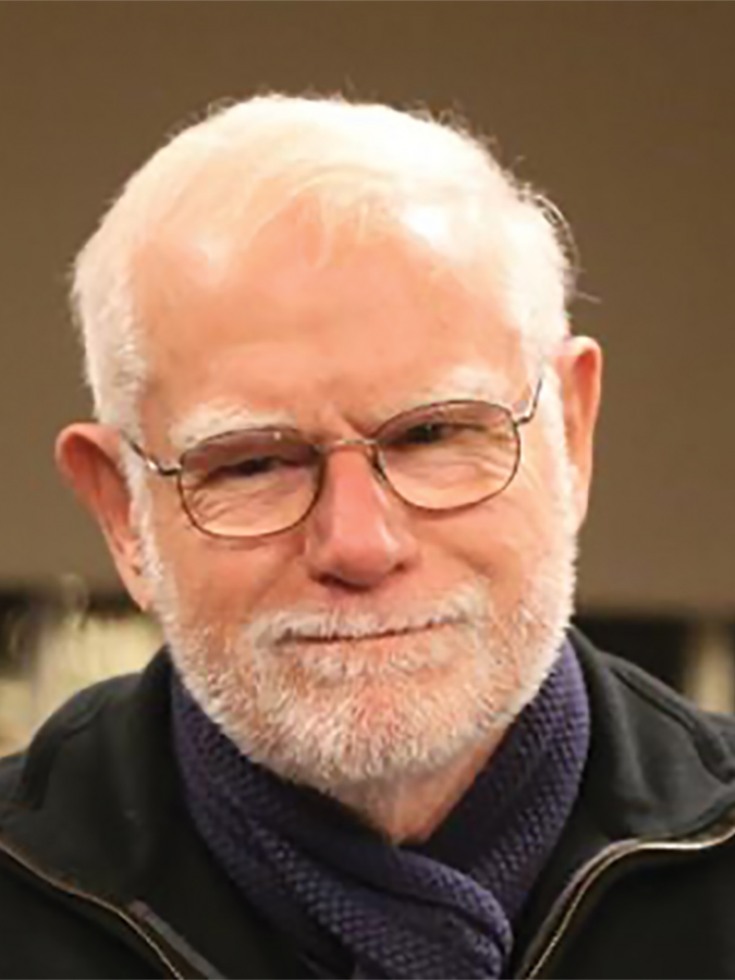

More than 35 years later, those green flecks, which turned out to be beads of volcanic glass, found their way to a lab at Brown, where geologist Alberto Saal showed that they contained surprising amounts of water. It was the first unequivocal evidence that the Moon’s interior, long thought to have been stripped of any water during its formation, wasn’t so dry after all.

“That has absolutely revolutionized our thinking about how the Moon formed and how solar system bodies interact,” said Jim Head, a professor of geological sciences at Brown who worked on the Apollo program and was inside NASA’s Mission Control Center as Scott and Irwin explored the Moon. “That was a tremendously important discovery that Dave and Jim made on that mission.”

It was one discovery among many for what Head said was one of the most productive scientific missions in the history of spaceflight.

“Everybody knows about the historic Apollo 11, but most people aren’t very aware of the subsequent missions,” Head said. “Apollo 15 was the first true scientific expedition to the Moon, and it was incredibly successful.”

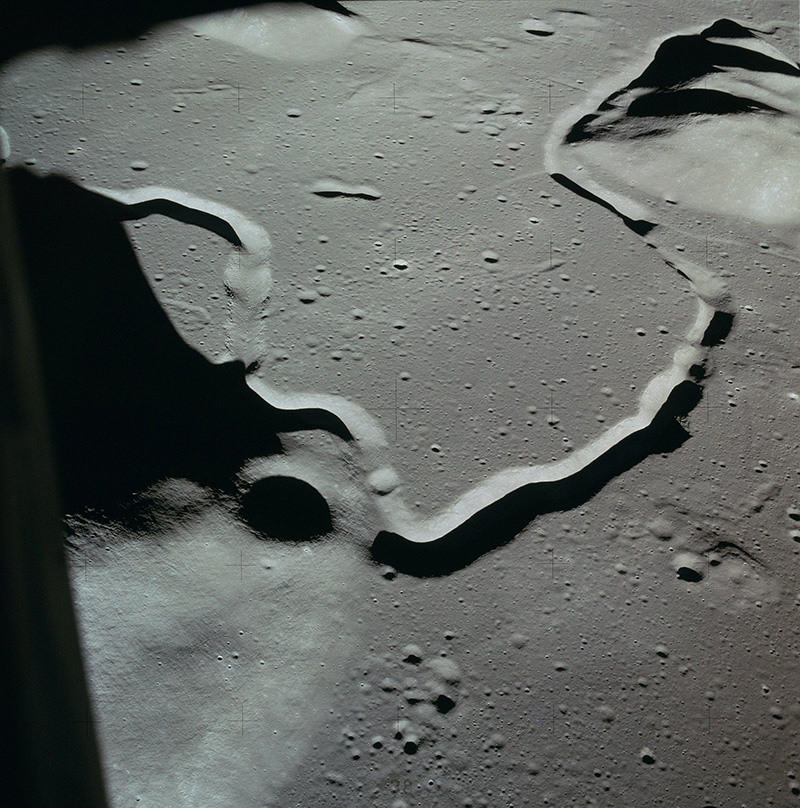

Apollo 15 was the first of what NASA termed J-type missions — missions with vastly expanded scientific capabilities. Apollo 11, the first lunar landing, demonstrated that a safe landing on the Moon was indeed possible. The next two landings, Apollo 12 and 14, achieved pinpoint touchdowns on rough terrain. Those technical feats set the stage for the tricky Apollo 15 landing in an area of high scientific interest: a spot situated between the towering Apennine Mountains and Hadley Rille, a deep channel carved by ancient lunar lava flows.

Head, an expert in lunar and planetary geology whose first job after earning his Ph.D. from Brown was on the Apollo program, played a key role in choosing that landing site.